Story by Ethel Navales

When I began reading Boat People: Personal Stories from the Vietnamese Exodus, I had no idea what was in store for me. I didn’t expect to find each page more difficult to digest than the one before it. I didn’t expect that I would need to pull away for moments just to process what I had read. I certainly didn’t expect to be on the verge of tears, but that’s exactly what happened.

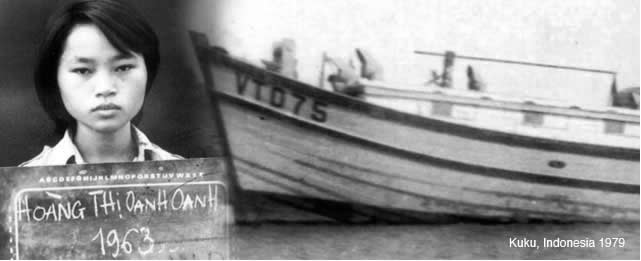

In riveting detail, Boat People brings together the heartbreaking stories of those who survived one of the largest mass exoduses in history – an exodus which had more than a million Vietnamese citizens fleeing their homeland after the Vietnam War. The book’s editor, Carina Hoang, was only 16 when she took part in this journey in 1979. Despite previous hardships – including her father being taken away for 14 years as a political prisoner, her house being confiscated, and nearly unbearable poverty – nothing could have prepared her for the difficulties that were to come as a refugee. “I was not aware of the risk involved,” says Hoang. “I did not realize that once I [stepped] foot on the boat, my chance of survival was very slim – it was something like 10 percent.”

Hoang’s account of her own experiences proves to be just as horrifying as the other stories in Boat People. “There were 373 people on board. It was so crowded that most of us sat with knees to our chins for nearly seven days,” she says. “We were tossed about by a violent storm; we threw up all over each other, and sat with the vomit and the stench for the rest of the trip.” As difficult as this may seem, the hardships of the journey were far from over. Hoang and the others on her boat were attacked by pirates, faced starvation and dehydration, and were quickly overcome with disease. “There were times when I didn’t think we would make it,” recalls Hoang. “It was God’s will that we lived while hundreds died and were buried in the jungle.”

Now, 34 years later, Hoang has dedicated herself to telling her story, as well as the stories of the other survivors. “My main motivation,” Hoang explains, “is to help my daughter, my nieces and my nephews know about their heritage and to understand why and how their parents fled Vietnam.” Of course, a task like this is no easy one. After months of searching and interviewing, Hoang and her co-editor, Michelle Lam, found many people who resisted the idea of digging up their past. “Not everyone we approached was willing to share his or her stories. Some found it difficult to relive their tragic past,” says Hoang, “especially when we touched the subject of the boat people being brutally and inhumanely attacked by pirates.”

Despite these obstacles, Hoang continued to work on Boat People because she understood how important it was to tell these stories. She points out that although the Vietnam exodus was one of the largest in history, many people do not know the enormity and details of this event. To help heal and educate, Hoang organizes trips back to the refugee camps. “Many families lost their loved ones while in refugee camps,” she says. “It is part of our culture to visit the graves of our loved ones regularly, but more importantly, it’s just hard to grieve as the loved ones died in such a tragic way and the families were unable to give their loved ones a proper burial. In some cases, people just couldn’t let go; thus revisiting the graves of their loved ones gives them a sense of comfort or a form of closure.”

Whether through organized trips, public speaking or Boat People, Hoang continues to fight to give voice to these stories. “I believe that as people are more informed, they will have better judgment about refugees and will hopefully approach the matter with more compassion.”

This story was originally published in our Fall 2013 issue. Get your copy here.