With her tour schedule and classes canceled, Jasmine Cho contemplates what she can do in her home city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to raise awareness for underrepresented Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. The answer remains: cookie decorating.

Imagine edible art that’s cute, memorable, relatable, nostalgic and even tastes good. These were some of the qualities that made Cho’s first entrepreneurial enterprise, Yummyholic, such a champion in both the culinary world as well as the expressive arts. Cho’s career was catalyzed back in 2010 with a single project, and “Character Media” even had a little something to do with it.

Back then, under our old name “Koream Journal,” “Character” kicked off an online contest called “Krazy K-pop!,” which asked contestants to submit homemade music videos for K-pop classics. Cho sent in a video of herself baking along to a fan mix of classic K-pop artists like H.O.T. and Wonder Girls. Although she didn’t win, her video made it to the competition’s final round and its success encouraged her to use YouTube to develop her baking portfolio after she decided to seek a pastry chef position. The stop-motion video she sent in now serves as a precious archive of the beginnings of her cookie art journey. From lip-syncing to giving TED Talks, Cho’s artistic and political evolution has paved the road to opening her own business and working with charities to raise awareness for AAPI notables from across history.

“Everything happened very organically. I knew that pastries were something I loved to do, they made me come alive,” Cho muses over the phone. “But I also had this sense of wanting to do something that was social justice-oriented. From the beginning, I tried to think of ways to intersect baking with social justice.” Cho’s philosophy of charity got her involved with a nonprofit organization, Beverly’s Birthdays, which throws birthday parties and baby showers for children and families who have experienced homelessness.

At the time, Cho’s custom cookies were already becoming a hit after she designed a cookie at the request of a friend, who had asked if they could have their face as one of the designs. The art went viral, and in the fall of 2016 the social media approval boosted Cho’s desire to make her work more than a snack. “Once I realized that face cookies have the ability to capture people’s attention, I wanted to start putting faces of people I felt were severely underrepresented onto cookies, and try to get people to pay attention to those individuals and their stories,” Cho says. “That medium became my platform.”

It sounds innocent enough, to ice a cookie with a face. But who chooses the face, what does that face represent, and why? Although DIY cookie art is fun and tasty, can it mean more than just sugar dressing? Especially when history connects many Asian Pacific Americans to sugar plantations. These are just a few of the questions that Cho encountered while developing her work as the world’s first (or at least best-known) cookie activist.

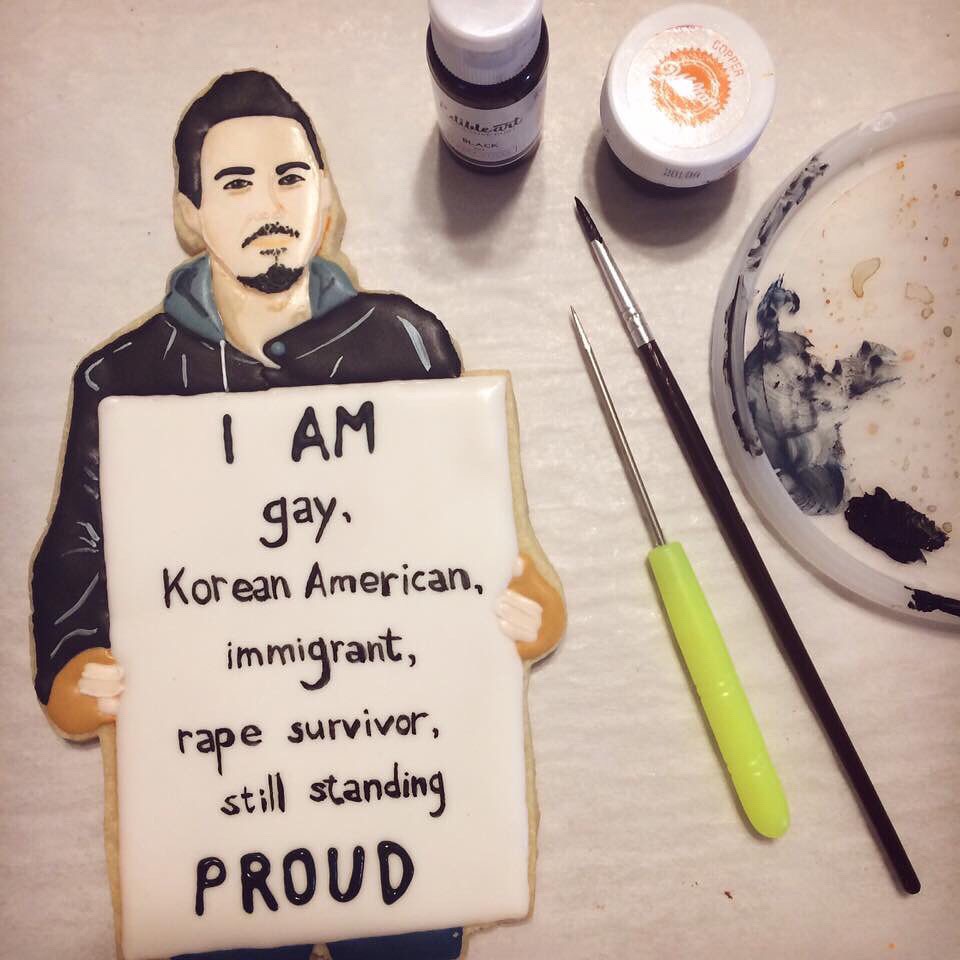

While reflecting on some of her more memorable cookie portraits, Cho explains that it wasn’t until 2017 that she intentionally made her cookies a political and historical statement. She had recently seen a photograph of an Asian man holding a sign in commemoration of the Stonewall Riots. The sign read, “I am gay, Korean American, immigrant, rape survivor, still standing proud.” “I remember I thought, ‘Oh my gosh! I have to recreate this portrait,’” Cho says. “His name was Ben Dumond, and I remember his portrait in particular. You kind of lose yourself to this; it’s the process of making art, and as you do you reflect on this person’s story and the courage it took for him to post that publicly.” After the inspiration for Cho’s Revolutionary Art exhibit came together, her collection of 11 cookie portraits was on display at the Pittsburgh City-County Building in 2017 as well as other local public art venues. Cho feels a responsibility to honor the identities and the stories she’s able to share, and she has no intention of minimizing individuals’ contributions to the world. The cookie-making process also helps her release emotions into something that proactively goes towards helping her community.

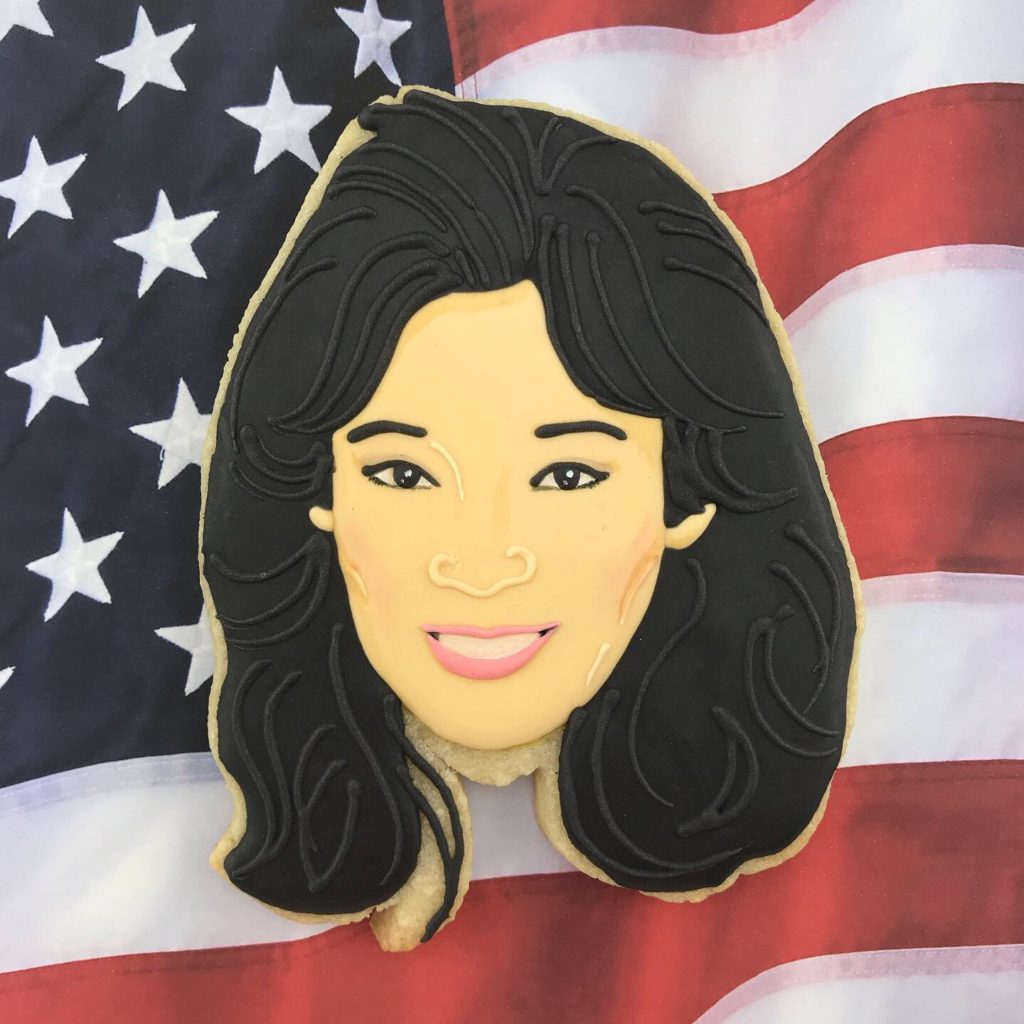

Cho also created a cookie portrait of Betty Ong. Ong’s story, although not too old, is one that many are unfamiliar with. She was one of the flight attendants aboard the American Airlines Flight 11, which crashed into the North Tower on September 11, 2001. Ong placed the call that led to all domestic flights being shut down, potentially saving the lives of thousands that day, and she provided a full description of the hijackers’ identities. However, Ong and her Chinese American heritage has rarely, if ever, been mentioned. “I don’t think you hear about people of color or women of color being part of those heroes and sheroes, so I didn’t think about Betty Ong until the recent couple of years,” Cho says. But after creating the portrait, Cho heard from several of Ong’s relatives that they were thrilled with her representation.

These memories, and all the portraits Cho has created so far, have worked toward furthering her personal research and practice of baking therapy. Although few studies exist in the latter field, most entrepreneurs can say they have experienced stress and anxiety when first developing a business. Things as simple as pricing can make any business owner question their self-worth, but baking therapy has rejuvenated Cho in the midst of figuring out the logistics. Her results have been so positive, she’s even returned to school to pursue a Masters degree in art therapy at Pratt Institute.

Through combining psychology, politics and food, Cho has also formed a partnership with the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, where she puts on a monthly show called “A Sweet Break with Jasmine.” Cho and patients host each episode, and viewers get to watch and explore cooking and baking. In the future, they hope to expand the program’s reach with a bedside baking kit, which would help patients in isolation still interact. Cho, whose upbringing as an Asian American has provided her with insight to these feelings of loneliness and invisibility, wants to ensure that she does everything she can to help all kids feel included. “Growing up in the ’90s as a Korean American, I felt less represented,” Cho says. “There was a sense of feeling invisible in my textbooks. I remember trying to figure out the history of Korean Americans for a research topic, and all of the history books were so limited.” History is full of iconic and influential Asian Pacific Americans, many of whom, like Cho, are making an impact by reclaiming their history and making it relevant to global audiences. “It makes me excited to work directly with sugar in a way that promotes or elevates our stories into the public,” Cho says.

The idea of dessert and pastry brings joy to many people. That sense of joy is important, especially today while many shelter at home, away from friends and family members. It’s that positivity that keeps Cho going, but she’s never felt that the art she makes is easy. “The sense of fulfillment is important—even though the work can be really heavy,” Cho says. “The process of cooking reminds me of what I love so much and helps keep me going.” These cookies offer a treat that’s accessible to people regardless of age or location. They provide a new way of viewing long-gone heroes, and those of the not-so-distant past. And these days, speaking out however we can feels more necessary than ever.