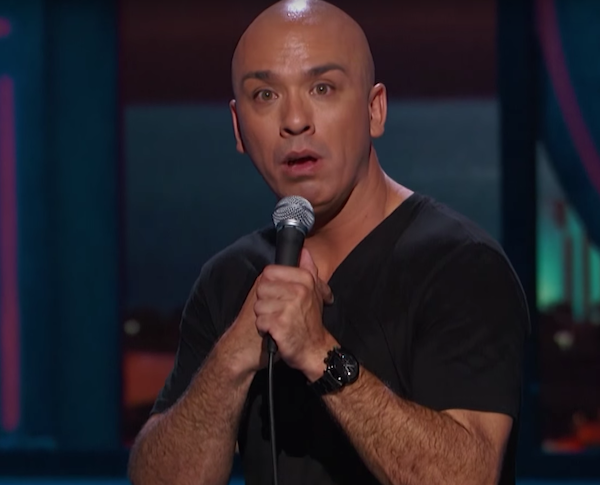

If you take a long and winding road way up into the tree-lined North Hollywood hills, you will arrive at a meandering driveway lined with big, fancy cars. You will park your car and you will venture into a charming bungalow replete with pool, a basketball court and a stunning view. That’s where you’ll find Jo Koy living the dream.

So how does one make one’s comedic dreams come true? With his light hazel eyes sparkling and his bright white teeth gleaming, he holds forth in his all-white dining room, where he recalls the hilarious, painful and extraordinary dues that he paid to get where he is today: He has hustled. He has worked incredibly hard. He has taken ballsy risks. He’s failed. And he’s dusted himself off and risen again. And yes, he has even lied when it made sense to exaggerate as a means to an end.

At the age of 46, Koy (born Joseph Glenn Herbert) has succeeded in becoming one of the most visible Asian American comedians on the scene today. In October, he sold out 11 shows at the Neal S. Blaisdell Concert Hall in Honolulu, breaking records for ticket sales of any single act in the history of the venue. Audiences flock to hear his pitch-perfect Filipino accent and his astute observations of Asian American family life. With his unique perspective as a comedian with a white American military dad and a Filipino immigrant mom, he’s become a rare voice for people of mixed heritage.

And yet, for Koy, the hunger remains. “I’m sure there are comics saying, ‘I wanna be where Jo’s at,’” he said. “But I still think I have another 28 more years to go. I’m not where I need to be. There’s so much more. If Kevin Hart can do arenas, I can do arenas.”

(Jack Blizzard/Kore Asian Media)

He’s been hungry and driven like that ever since he was a prepubescent grade-schooler, taping the Eddie Murphy “Raw” poster onto his wall like some kind of vision board for future comedic success.

When the white side of his family gathered for holidays, they would passively watch TV or go to movies. But on his Filipino side, he and his siblings were the entertainment at family get-togethers, telling jokes, singing or dancing. He draws on childhood memories for his act, like his mother reaching for the Vicks VapoRub to cure all of his ailments — even pneumonia. Or when his grandmother, sick with cancer, would beg in a feeble voice for him to come closer, only to grab his penis and squeal with joy: “I got your titi!” Laughing, he remembers himself saying, “Goddamnit, Grandma!”

But it wasn’t all good times back then. When he ventured off the military base where he grew up and where mixed kids were the norm, his family would be confronted by the cold reality of racism and ignorance. Many Americans back then were unaccustomed to seeing Asian, much less mixed-race, families. He remembers a little white kid spoiling his family’s happiness at winning a color TV by pulling his eyes at his mom and hurting her feelings.

“My work is my life,” Koy said. “And that’s my meaning, to be able to tell stories and to make myself as vulnerable as possible, and tell what other people probably keep secret. That’s the funny part of life. That’s the realest sh-t you could put out there. And when you do that, people relate. That’s the true meaning of my art. That’s what I love about stand-up. Just being able to tell people the truth.”

But when Koy burst onto the Vegas comedy scene in the mid-’90s, he discovered a scene in decline due to the rise of cable TV. Comedy clubs were shutting down because people preferred to stay home and watch stand-up from the comfort of their sofas instead.

Imminently resourceful, he’d create his own when venues weren’t available. Back in the early ’90s, he tried to talk the UNLV Filipino American Student Association to sponsor an Asian American comedy night featuring a then-unknown Bobby Lee at a ballroom in the student union. But the student organization shied away from the opportunity: “All they had to do was sign the f-cking paper. And they didn’t sign the paper. In general, Asians stuck to their little core and they didn’t go out of the box. They said, we don’t want to support that because we don’t know what it is. We’re not ready for that. Let’s stay here in our little groups and do our little group things. I think the time wasn’t ready. It was a weird time. I remember I was so f-cking mad that they didn’t show up.”

Undaunted, Koy convinced a frat boy to sign the appropriate paperwork and bring all of his people out to the event. It turned out to be a huge success. “I remember looking at Bobby and going, ‘We have a show, bro!’” he said with characteristic exuberance. “And then the sorority came. I was like, ‘What!’ The whole front end was packed. I was so excited.”

Back in those days, Asian Americans had even less visibility than they do now. And as a non-white person with hip-hop sensibilities, it simply made sense that Koy would seek acceptance in a well-established minority comedy circuit: “All I did in the beginning was black comedy,” Koy said.

(Jack Blizzard/Kore Asian Media)

To pay the bills, Koy worked at the front desk of the Alexis Hotel, giving him access to ballers and shot callers, especially when the hip-hop streetwear-centric Magic Convention came to Vegas. It was about 1994, and he coveted the Dada Supreme cap that he had seen in rap music videos. To his amazement, the owner of Dada Supreme checked in at the Hotel, spreading out stacks of Benjamins across the counter to pay for six rooms.

Seizing the opportunity, Koy talked the streetwear mogul into giving him a few caps for free. Then he blurted out, “I do a comedy show.” And that wasn’t necessarily a lie, but it wasn’t quite true… yet. He hoped to convince Dada Supreme to sponsor him so that he could wear the latest styles during his acts on stage. The owner said to send him photos of him wearing the hats to his company and he would send more clothes and accessories. But Koy’s calls went unanswered.

So Koy decided to take matters into his own hands. He bought his own Dada Supreme outfit head-to-toe, hired someone to videotape one of his shows wearing the clothes, and waited until the following year’s Magic Convention. He sneaked into the hall with his videotape in hand and lurked around the Dada Supreme booth. “I literally hovered around that damn Dada booth the whole damn day,” Koy said, with the fire burning in his eyes like the Magic Convention was just yesterday. “I remember looking to my left, and then I saw the owner right there. I remembered his face, the goatee, how he talked.” He recognized Koy and expressed regret that the comedian’s phone calls went unanswered.

Once again, Koy brought up his comedy show and mentioned that he would love for Dada to sponsor his entire production. “I wasn’t lying,” he said, “but I made it sound like it was this big, giant Vegas show.” At this point, Koy was renting the Huntridge, an old-timey local movie theater in Vegas, to host his own shows. He paid for the venue by convincing local businesses, like auto tune-up shops and optometrists, to print coupons on the back of the tickets. Dada’s marketing guys agreed to set up a meeting. The timing was right, because they happened to be looking for a comedy show to sponsor, he remembers.

(Jack Blizzard/Kore Asian Media)

“So we put together a fake business plan. Price breakdown. Headshots. A mock poster of what my event was going to look like. It was a microphone on a stool and it said, ‘Dada presents …’ And then I had all these comics that I knew that I could kinda get but I put them on there anyways. I put the hotel rooms, the flights, the rent for the Huntridge, insurance, radio ads. It came out to four grand. I remember asking my friend, ‘Is this too much?’ And he was like, ‘Just bring it to him. If they give you less, then they give you less.’”

Koy nervously handed the Kinkos-made business plan to the suave and stylish Dada executive. “He had this big afro and light-blue sunglasses,” Koy said. “He was like, ‘All right, cool. When can you do it?’ He didn’t even look at my business plan! I could have asked for $10,000!”

After that, Dada sponsored Koy’s ascent into the black comedy circuit, from his championship performance at the cutthroat Apollo Theater in Harlem to his breakthrough at the “Def Comedy Jam.” Step after step, Dada had his back.

Carlos Parrott, who was the vice president of marketing at Dada Supreme back then and has been a huge booster of Koy’s career ever since, remembers the comedian’s hustle like it was yesterday: “Even though he’s blown up and he’s got enough fans, he’s the only comedian who goes out after his shows and shakes everyone’s hands, signs whatever they have, takes pictures with them. If it takes 20 minutes or an hour or two hours, he will go through the entire line. That’s inspirational to me. He doesn’t have to do that, but he’s smart enough to realize that it’s essential to build a real connection with the fans.”

Beginning in 2015, Koy and his manager launched a relentless campaign to invite Netflix executives and convince them that Koy had a place in the 2017 calendar. Initially, they balked, but ultimately Koy got his way and by spring, “Live from Seattle” was available on Netflix. So how’d he do it? “You just have to follow these simple steps for the next 28 years and you will be here. Just enjoy the process and enjoy the ride.”

Photos Jack Blizzard

Style Shaojun Chen

Makeup Jayme Kavanaugh

Read more about Jo Koy & other Asian Pacific Americans making their marks on pop culture in our 2018 annual issue, available for order here!

Watch behind-the-scenes with Jo Koy at the photo shoot below: