A local columnist’s attempt at downplaying the severity of the alleged race-motivated murder of Vincent Chin in 1982 is eliciting an angry reaction from the Asian American community.

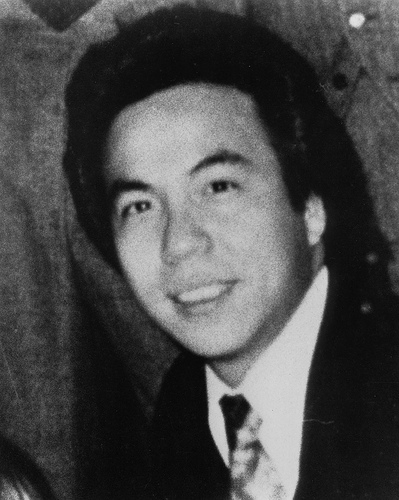

In his recent column, “What we all assume we know about the Vincent Chin case probably isn’t so,” inThe Detroit News, reporter Neal Rubin dismisses that the killing of Chin, a 27-year-old Chinese American, was racially motivated. Rubin bases his claim on the account of a reporter who covered the original case to suggest that it was a drunken brawl at a strip club that led to the murder.

[ad#336]

Chin died at a hospital on June 23, 1982, four days after Ronald Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz, fatally beat him with a baseball bat. Prior to the beating which occurred on the streets, Ebens and Nitz allegedly hurled racial epithets at Chin at a local strip club, saying, “It’s because of you (bleeps) we’re out of work!” referring to the loss of U.S. auto manufacturing jobs due to the growth of the Japanese auto market.

The case stirred a public outrage especially among Asian Americans after the two men received lenient sentencing. Neither Ebens or Nitz went to prison and each of them only drew a fine and three years of probation.

“Two unemployed autoworkers beat Vincent Chin to death because they thought he was Japanese and they drunkenly decided he had cost them their jobs,” Rubin’s article states. “That’s an accepted piece of history.”

But Tim Kiska, the former reporter who’s now a journalism professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, tells Rubin, “Almost all of that is wrong.”

Rubin goes on to provide Chin’s blood alcohol content–.14–without doing the same for the perpetrators. He also writes that it was Chin who initiated the fight as he and his friends outnumbered Ebenz and Nits at the bar.

Ebens, one of the two perpetrators, also denied that the murder was race-motivated in an interview withSFGate.com in 2012.

“It should never have happened,” Ebens said at the time. “[And] it had nothing to do with the auto industry or Asians or anything else. Never did, never will. I could have cared less about that. That’s the biggest fallacy of the whole thing.”

Stewart Kwoh, the president and executive director at the Asian American Advancing Justice, has responded to Rubin’s article by issuing the following public statement on behalf of his organization:

[Rubin’s] effort to correct the historical record would be more persuasive had he bothered to interview any of the individuals directly involved in either the initial criminal trial or the subsequent federal civil rights prosecution – including me.

Rubin’s own biases are suggested when, in mentioning that Chin and his murderers had been drinking, he provides a blood alcohol reading only for Chin. Why? Were the statistics not available for the perpetrators? Did Rubin even attempt to find out? Unlikely, because finding out may have undermined the narrative that he presents as the real story: that a drunken, out-of-control Chin brought his death upon himself.

Momentous periods in our history should be subject to reexamination, including the Chin case, since historical accuracy is critical to our understanding of who we are as Americans. But an effort like Rubin’s, marred by his failures and biases, is difficult to take seriously. Coming on the eve of this year’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, his article is especially egregious, a wrongheaded minor coda to the story of tragedy and eventual triumph that the case of Vincent Chin represents for Asian Americans.

[ad#336]