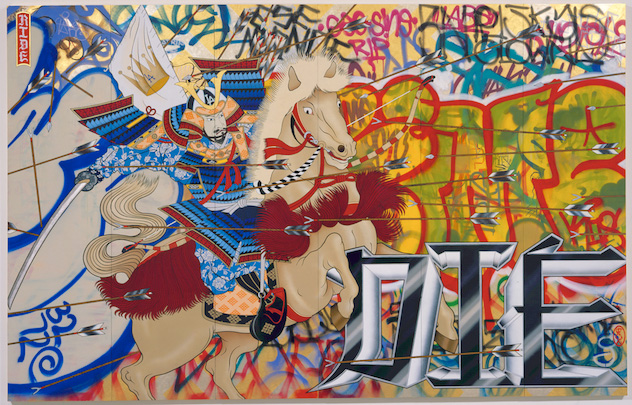

An embattled Edo-era samurai and his stressed steed are assailed by an onslaught of piercing arrows. The look in the samurai’s eyes is calm yet driven. The ensuing chaos is represented by graffiti tags, cholo writing and fill-in throw ups. The “Twilight Zone”-like juxtaposition makes it seem like he’s bursting out of a time portal into early ’90s Los Angeles street culture. An L.A. Dodgers logo is emblazoned on his otherwise traditional helmet adorned with golden antlers.

The artist responsible for this piece, entitled “Ride or Die,” is Gajin Fujita, who created it with spray paint, paint marker, paint stick and gold leaf on 84-by-132 ½-inch wood panels.

Born and raised in East L.A.’s predominantly Latino neighborhood of Boyle Heights, Fujita learned early on how to adapt culturally to an area known for gangs, drugs and crime. It was on his own block where the danger zone was minimal and a tight-knit community reigned supreme.

“We were out there riding our bikes, playing football with all the kids on the block,” Fujita said. “The neighborhood [Latino] families knew I was different, but they were real cool, welcoming us into their homes, giving us food.”

His artistic influences were also rooted in a strong Japanese home. “In our house it was all Japanese, and you have to respect your family, which was totally cool, too,” he said. “I got the best of both worlds.” His father was an artist and his mother worked in art restoration.

Fujita became heavily involved in graffiti while attending the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies in 1985. “That’s when [the book] ‘Subway Art’ came out, and that was the craze — breakdancing, hip-hop and graffiti,” he said.

He joined a Mid-City crew, Kidz Gone Bad, and later went on to join Kill 2 Succeed, one of L.A.’s original prominent graffiti crews. Fujita made a name for himself using the moniker HYDE, which can frequently be seen amongst the tags piled onto the background of his paintings, alongside signatures from his friends and crewmates.

At East Los Angeles College, Fujita came across Japanese tattooing, which he said “blew my mind.” Later, while pursuing a BFA at Otis College of Art and Design, he met art professor Dave Hickey, who became his mentor. Hickey helped him get an MFA scholarship at the University of of Nevada, Las Vegas.

“At one of Dave’s lectures he said that ‘art should be a violation of expectations,’” Fujita said. “That slapped me in the face hard.”

Invigorated and looking for inspiration, he came across an old photo he took during a trip to Japan. “The Golden Pavilion in Kyoto sits in the middle of a pond, and it’s all gold, reflecting off the pond. And it looked sick … it got me entranced. I thought about the violation effect — what if someone were to hit that with paint? That’s where it started.”

Fujita’s career transcended the confines of graffiti into the realms of high art. “Tattoos and graffiti were looked down on at the time, and he brought that into a classic mix,” said Scott Grieger, Fujita’s painting professor at Otis. “He brought high art down and low art up. You’re getting both sides of the coin. There were people that understood it, unlike an older generation. It’s focused, and it has obvious quality.”

His breakthrough moment arrived in 2001 via the Beau Monde Exhibit in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Curated by Hickey, it boasted a roster of well-established original American artists.

“Dave gave me my first break on the big stage,” Fujita said. “It launched my career professionally.”

Fujita is often labeled a “graffiti guy,” which he thinks is a misnomer, but he understands the perception. “Graffiti has become pop,” he said. “I don’t really care. I’m an artist, not just a graffiti artist. It’s layers of different elements of my life. Graffiti is a rebellious act of vandalism. If it’s not illegal, it’s not graffiti. I work in a studio.”

In 2012, after a string of successful exhibitions, Fujita moved from East L.A. to an attractive, scenic multi-level home on a steep hill above Echo Park. This is where he labors anywhere from three to six months to complete one painting, which commands prices in the high six figures. His clientele consists of private collectors, including Ronald Meyer, NBC vice chairman, and museums such as the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. With nearly 20 years under his belt as a professional artist, Fujita has found his stride.

“My work is based on cultural identification. When I first started, I was trying to mock my culture. That’s what you need to provoke,” he said. “But I do respect my culture. I paint these samurai because that’s what I like seeing.”