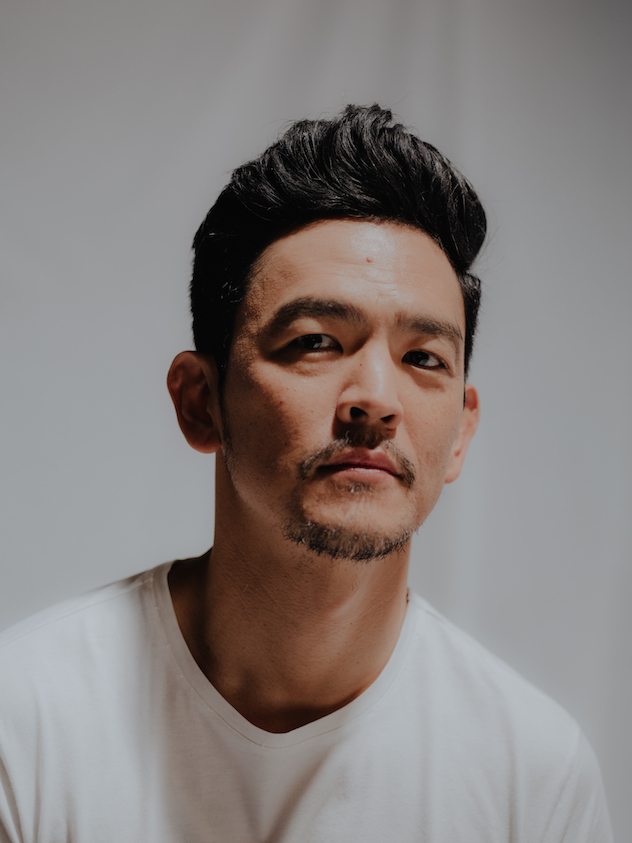

John Cho is on a search for authenticity. “I have a looser and looser grasp on it as the years go on,” Cho muses one sunny August afternoon inside KORE’s office.

As he weaves his thoughts between different subjects — from his relationship to his race (what does Asian American mean when you’re a Korean immigrant who just wanted to fit in?) and the characters he chooses to depict on screen (which almost always leads to a larger conversation on representation) to measures of success (“The career is just something that is not a part of me; it’s something that walks next to me, it’s not me”) — one thing becomes clear: At the end of the day, Cho just wants to make good movies that allow him to stretch his creative muscles. And so it is with “Searching,” his new film.

Helmed by first-time feature director Aneesh Chaganty, the indie thriller explores the grief of David Kim, whose teenage daughter (Michelle La) goes missing following the death of his wife (Sara Sohn). The entirety of the film plays out through David’s eyes, which functions as a camera of sorts as we watch the story unfold on his computer screen.

Chaganty, a self-described John Cho fanboy, and his writing partner Sev Ohanian wrote David with Cho in mind, but it required several entreaties before the actor came around.

“[The film] was out of my comfort zone, so I said no at first,” Cho says. He’d seen “Unfriended,” really the only approximate example of a movie that takes place completely on a digital screen, and didn’t like the idea of acting for a static camera. And he definitely did not want to feel as though he were making a YouTube video. But at the same time, he did like the screenplay, if only interpreted as a more traditional picture, and was flattered most of all that the role — an explicitly Korean American one at that — was created for him.

To his credit, Chaganty doesn’t give up easy. He sent off a few nervous texts, and Cho eventually acquiesced to a meeting. “When we met face-to-face, I just really liked [Chaganty] so much,” Cho says. “He had vision and conviction and a lot of charisma, and he convinced me it would be a movie. I just had a feeling about him. So I said yes.”

(Joyce Kim/Kore)

Shooting took 13 days. Most of that time was spent with Cho acting while facing a blank laptop mounted with a GoPro. He calls the experience “disorienting.” Cho, who is 46, reckons it’s a generational thing — while he’s seen his two children in complete comfort taking selfies and speaking to a camera, he’s never particularly liked the one-eyed machine.

Cho’s struggle with the idea of a camera plagued him in his younger years as an actor, when he would act for the camera, not for his co-stars. “It’s hard because it’s a big scary thing, and you want to please the machine,” he says. “I spent my whole career having to get over that, and learning to do it looking at people in the face. That’s how you do a scene. And then here, the webcam was 6 inches from my face.”

His character David, who’s lost his beloved wife to illness, is as humdrum as single dads go. He works his 9-to-5 cubicle job, shares dinner recipes with his brother (Joseph Lee) and tries his best to connect with Margot, his only daughter, though he’s often blocked out of her teenage lifestyle. When she mysteriously disappears, David’s entire life unravels as finding Margot becomes his obsession, with an empathetic detective (Debra Messing) attached to the case.

La, the first-time actress who plays Margot, says she learned the importance of collaborating with the crew on set from watching Cho. “During his scenes, he would work with Aneesh to throw out ideas,” she says. “He’s very curious. He understood the director’s vision and married that with his own character.”

Cho owes much of his early work to first-time filmmakers like Chaganty, from Justin Lin’s debut “Shopping for Fangs” and Chris Chan Lee’s “Yellow” to Paul and Chris Weitz’s “American Pie” and, most recently, Kogonada’s indie drama “Columbus.” “I just wouldn’t be anywhere without first-time filmmakers,” he says. “I love the different perspectives they have. They don’t know the rules yet, they don’t know how things are impossible yet.”

For a time, Cho says, he grew disenchanted with filmmaking, spoiled by being in the business. He’d watch a film and see the script in his head. He’d watch a TV episode and picture the costumer just beyond the edge of the screen. It took awhile for him to come back around, but now he appreciates movie magic more than ever.

Recently, he’s been revisiting older cinema, like the 1951 Gene Kelly classic “An American in Paris.” The movie’s opening left such an impression on him that he shared the clip with Kogonada. “Gene Kelly wakes up in this tiny apartment. It’s a single shot, it’s tightly choreographed,” describes Cho. “He gets his breakfast, he pulls up his bed, he gets his socks out of the drawer. It’s all a half-dance. Everything is entertaining. You learn all this stuff about him. In the end, he’s an artist — he comes up to a drawing of himself and uses his hand to smush the frown upside down into a smile. I was like, that was like 80 seconds and it was the most entertaining 80 seconds I’ve ever seen. There’s professional admiration in how clever that was and how well-executed and how great Gene Kelly is. With men, I like to look at different acting styles and different ideas of masculinity.”

Getting into the nuts and bolts of filmmaking is one of Cho and Kogonada’s favorite subjects. “We always talk about how to do things with fewer words. That’s one of the themes we return to a bunch of times.”

Chaganty, who’s another frequent movie chat partner of Cho’s, calls him “a great analyzer of things.” Chaganty adds, “It’s never small talk with him. It’s always like large, macro connections between point A and point B.”

Then Cho wants to talk about getting older. Hearing him ponder his age is startling in the sense that we still best know him, some two decades into his filmography, as the young, bright-eyed men he’s so often portrayed on screen.

“You look out onto the hills and you see all those houses. Me, I think about all the actors who are in those houses from my childhood who were big-time stars, and I wonder what their lives are like now, how they dealt with the third act of their lives,” Cho says. “Then I wonder how I’ll deal with it when that time comes.”

He’s started imagining scenarios in his head in which, years from now, someone tells him he is too old to play a part, or says, “John, you’ve gotta stop. We don’t like you anymore. We think you actually kinda suck.” On the flip side, he’s no longer stuck playing 25-year-olds. Now it’s onto the meaty stuff. “It always seemed like younger parts were primary colors and not as interesting as the older parts,” he says.

(Joyce Kim/Kore)

(Joyce Kim/Kore)

Cho was born in South Korea and grew up in Glendale, California. He fell into acting in college but never had high expectations for a life in it. He figured he’d give it a few years of nabbing one-liners (“MILF!”) and cobbling together money for rent before “getting a real job.” The acting gigs, of course, took off. He’s built a career stacked with blockbusters, indie favorites and TV shows (which includes being the first romantic Asian American leading man on a network series; though that show, “Selfie,” met a premature end, it’s still a telling achievement).

For “Searching,” Cho formed a close emotional connection with David just on the basis of being a parent himself — and because the role was to him what few others ever had been. It normalized an American family that looked like his own by putting them in a story not based on them being Asian.

“Somebody writes this Korean American guy, and they have a Korean person in mind for the guy. But his family didn’t have a conflict that was cultural. It wasn’t about him being Asian American,” he says. “Many times, Asian American films are about culture. They’re saying the old way is this way, and the young person says, ‘No, I’m an American.’ I mean, it’s certainly what I’ve lived, and I’m not saying those stories aren’t valid. But I’ve seen it so much that [“Searching”] was refreshing.

“There’s two things I’ve seen most. One is the super justifying of an Asian character by adding lots of cultural signifiers. The other way is, the character’s white and then they cast me. I’m grateful more, I guess, to play the white character. They’re usually better written, fuller. I just never thought of that as the end game. Like, this is the end game to me. “Searching” is the end game.”

In 2016, Cho found himself pushed to the front of the online movement calling for increased Asian American representation in media when a hashtag, #StarringJohnCho, used Photoshop to superimpose his face over the heads of white guys, the kind who lead tentpole franchises and romantic comedies, in movie posters. The images went viral across social media.

Not that the campaign alone made Cho the face of the conversation — headlines about Cho have always come accompanied by notes on representation, thanks to his long-standing status as one of Hollywood’s more prominent Asian American talents.

Though Cho cares about the API community, he’s never been comfortable being its poster child. “I used to be — still am — reluctant to be a part of the narrative that my films were changing perspectives on Asian Americans,” he says.

Because it feels like a weight? “No. It feels noble. And I don’t feel noble. I’m trying to do things that tickle the artistic bone,” he says. “I realize what I like about making films, the best thing is doing very big and difficult things with a whole bunch of people and feeling that extraordinary satisfaction. It’s always so much bigger than anything I could do alone. I feel like politically, too, we’re making something big together. In that way, I feel a sense of pride about that narrative.”

When Cho saw the final cut of “Searching” for the first time, he was astonished by how effectively the wholly on-screen format worked as a frame for what was otherwise a classic thriller. On top of that, this had been a movie made on a shoestring budget. Cho shot Chaganty a text after it ended: “You have contributed to the vocabulary of cinema.”

The year and a half of editing that followed filming had been a grueling nightmare, done on two iMacs that kept crashing every one or two hours. So getting that text was for Chaganty a “huge, huge relief.” Chaganty says, “Having that scale of a response from John, his whole team and Debra’s whole team, it was our first really major vote of confidence.” After premiering at Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, the film, which won the NEXT Audience Award, was snatched up by Sony Pictures Worldwide Acquisitions.

“Searching” shares its theatrical release month with the debut of two other Asian American-led stories, “Crazy Rich Asians” and “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before.” Driving around in Los Angeles, Cho’s passed the vibrant posters of the former, in which two Asian actors, Constance Wu and Henry Golding, are locked in an embrace.

I ask what he thought of that. Is this a new era? “Maybe it is a turning point,” he says. “We have to work. If there is a movement, it’s a generational shift. I feel that movement is not external but internal. Within our community, it’s a redefining of what we say our limits are — it’s within us. The fact that we’re posing the question means it is a moment.”

Photo by Joyce Kim

Styling Jeanne Yang

Grooming Paige Davenport