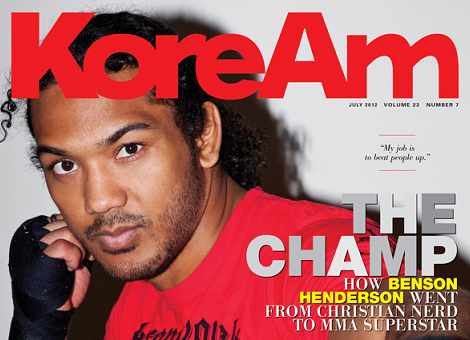

The Champ

Benson “Smooth” Henderson wants to be the greatest fighter ever. He’s already on his way.

by EUGENE YI

photographs by YANN BEAN

Benson Henderson has never won a fight. No, really.

“My buddy and I got jumped … for like 45 seconds tops, maybe a minute. And they ran off. And we were like, ‘No, no, don’t leave, come back. We’re not done yet, guys!’” Henderson said, laughing.

That he lost this one street fight back in college is, of course, irrelevant, now that he is the champ of the toughest division of the biggest mixed martial arts league in the world. He tells me this story in the lobby of the hotel near the studios of Fuel TV, where he has finished taping his first few minutes as a television commentator. It is a logical next step for a fighter whose career is ascendant. He won the lightweight UFC belt in February, after breaking Frankie Edgar’s nose with a vicious upkick before a reverent crowd in Saitama, Japan. He stands undefeated in the Ultimate Fighting Championshp (UFC), where he made his debut in April of 2011, five years into his professional career. His overall MMA record is 16 wins and two losses, and he’s never lost twice in a row.

He also just bought the MMA Lab in Glendale, Ariz., the gym where he started five years ago, scrubbing toilets in exchange for training time. And he’s got a rabid fanbase in South Korea, giving him an international appeal. He cuts a striking figure in the octagon, smoothing his wild mane after every exchange, escaping from seemingly decisive submissions, and splitting the difference between confidence and cockiness just enough so that you think he might just be the next big thing. The MMA is in a state of flux right now, searching for the next marquee names to attract the casual fan. Henderson has been called a rising star for some time. It would seem that Henderson has arrived.

Henderson was born on an Army base in Colorado Springs, Colo., the second son of an African American soldier and Kim Seong-hwa, a Korean woman he met while stationed in South Korea. The couple married and moved to the States, but divorced soon after. Kim moved the family to Federal Way, Wash., an old logging town between Seattle and Tacoma with a vibrant Korean American community. She ran a series of small businesses, sometimes several at a time, to make ends meet.

“She would leave at 8 a.m., and she’d come back at 2 or 3 in the morning, probably leaving her waitressing jobs at one of the Korean gambling places,” said Henderson.

The long workdays left little time for child rearing, but Henderson said he and his brother Julius grew up under the watchful eyes of a cadre of his mother’s friends, women he still refers to by the Konglish construction imos, or aunties.

“I didn’t know they weren’t blood-related until I got to my freshman year in college, and I thought, ‘Wait, you’re not really my aunt,’” he said.

Many of his imos had biracial children themselves, and he grew up as part of a diverse extended family.

“I thought of myself as pretty much as average as you could get,” he said. “I was nothing spectacular. No sad story, no triumphant story. Just an average American.” But many of Henderson’s childhood friends, from his recounting, did not have as easy of a time.

“A lot of my cousins, a lot of my friends, who are the exact same as me … they all say, ‘Oh no, growing up, it was hard for me. My friends all said this, and my parents said this. And I was confused and yada yada yada,’” he said. “Maybe I was so laid-back, I just viewed the world in a different light. I didn’t have a hard time at all. I was completely fine.”

Henderson’s mom signed him and his brother up for taekwondo lessons when he was about 10. The athletically gifted Hendersons quickly got their black belts, but the family moved soon afterwards, cutting the martial arts training short. In high school, though, Henderson found wrestling. “It’s my first love,” he said. And like many first loves, it would cause him much pain.

“In college my freshman year, I got the crap beat out of me every day. I literally left practice every day sad ’cause I just got beat up every day. A 17-year-old kid wrestling grown men, getting the crap kicked out of [him],” Henderson said in an interview with MMAWeekly.

The kid grew up to be an all-American, graduating from Dana College with a degree in criminal justice and sociology. He had a job lined up for him with the Denver Police Department until some friendly smack talk led him to take on a cagefight on a dare.

“I’m not a tough guy. I’m not a Terry Tough Nuts, a Billy Badass. I’m pretty laid-back. I like to read books. I like to use words to solve my problems. So I’m definitely not the guy who you would … pick to be a fighter,” said Henderson. His friends, apparently, agreed, and dared him to take on an amateur cagefight. “I was kind of stuck,” Henderson said. So at a local fight night in Omaha, Neb., Henderson stepped into the cage and, to his surprise, won his first competitive fight. And now? “My job is to beat people up,” he said.

The walk-out is a hallowed tradition in the fight game, with song and attire providing a glimpse into the personalities of the fighters. Henderson’s choices seem to be programmed against type. In his earlier fights, he would often approach the octagon wearing eyeglasses and a T-shirt over tight wrestler’s compression shorts, making it look like he forgot his pants. His music tends toward the God-fearing and funky, as one would expect from a self-described “Christian nerd.” Though he said he didn’t grow up “overly religious,” he did have role models early on.

“During the formative years of my life, right when you were like 13, 14, 15, just deciding who you were going to be … I had my two older cousins who looked after my brother and I,” he said. “They said to come out to church, so we would spend all day Wednesday at church, youth group, and then all day Friday, all day Saturday, all day Sunday.” It instilled in the young Henderson the value of faith. His Twitter description reads: “just your average joe, trying to live the american dream … oh yeah and my best friend was born in a manger ….”

Henderson is apparently no fundamentalist, though. Following President Barack Obama’s announcement in support of gay marriage, the fighter Tweeted,“I am Christian & I do support gay marriage.” Some of his followers disagreed sharply, but Henderson didn’t budge.

The other aspect of Henderson’s walk-out that is impossible to ignore is his unabashed embrace of his Korean heritage. He has several tattoos in Korean; the one on his upper right bicep says “champion,” and the words for “strength” and “honor” run down his right rib cage. Cameras often zoom in to his enthusiastic mom in the audience.

Fans in Korea have taken notice.

“Benson Henderson is an icon who represents not only the sport of mixed martial arts, but also Korean power,” said Seungjun E, a writer for Korean MMA site MFIGHT.

The enthusiasm is certainly in keeping with South Korea’s recent track record of wildly embracing successful biracial athletes (see Ward, Hines), a notable departure from the nation’s checkered past of shunning mixed-race individuals. A knowing Korean fan can’t help but notice a familiar set to Henderson’s eyes, a certain squatness in the legs. He has previously professed to KoreAm his love ofkimchijjigae and how he can eat “rice and banchan” for every meal. Henderson endeared himself to Korean fans at his UFC debut on April 30, 2011, according to E, who said in an email interview, “Henderson was carrying a large South Korean national flag. It had been signed by fans and fighters from Korea, such as the current UFC featherweight contender ‘The Korean Zombie’ (Chan-sung Jung), and was sent to Henderson by MFIGHT. Henderson was showing what his real identity was in front of not only the UFC record-breaking 55,724 spectators in attendance, but also the people watching him from Korea.”

Henderson’s fame spread further in South Korea when he visited twice in the past six months, along with his mother. It was his mother’s first time back since she left the country in the early 1980s.

“She will get to see many of her family members for the first time in years, and I will be meeting them for the first time EVER! Being able to share this trip with my Eomma makes it so much more special,” he said at the time.

The trip was heavily covered by the Korean media, according to E, and helped spark an interest not only in Henderson’s story, but in the sport as well.

“If it wasn’t for Henderson and [Chan-sung] Jung, more Koreans would still think of MMA as a violent sport which should be banned (or even not know about the sport at all). All of that has changed in a period of not even a year,” said E.

Former heavyweight boxing champ Floyd Patterson once said, “Winning after all is easy. It’s losing that requires courage.” Henderson’s great loss came in December 2010 against Anthony Pettis. It was Henderson’s last fight with the WEC, a league that was merging with the UFC, and he was defending his lightweight title.

Pettis, a third-degree taekwondo black belt, is a pesky and clever kicker, and the fight was close until round 5, when he landed an impossible flying kick off the wall that floored Henderson and ultimately won Pettis the fight in a unanimous decision. It was no doubt a surreal moment for many Koreans to watch a Latino American devotee of a Korean martial art deliver a flying kick to the face of a biracial Korean American. There’s probably enough fodder for many drinks’ worth of discussion regarding the inculcation of Korean culture into mainstream American society, and about Asian American masculinity in general. But the only real takeaway was a personal one: it made Henderson a better fighter.

Anyone who doubted his ability to turn it around would not have known how he had coped with years of losses as a collegiate wrestler, using his humiliation to hone himself into an all-American. Or how it was not his early victories as an amateur mixed martial artist, but his one loss that led him to dedicate himself in earnest to being a professional fighter. The Pettis kick will live on as one of the most spectacular strikes in mixed martial arts history. But Henderson knew how to move on.

“I didn’t want to let that [moment] define my MMA career,”he said. “It was a mistake. I lost. I can accept that. Sucks, but, it happens. But I didn’t feel that it was necessary to switch things up wholesale … I thought we had a pretty good formula for success. I was pretty much successful in all of my fights up to that point. I’ve been successful since then in all my fights.”

Though a hallowing of work ethic is one of the great cliches of sports, in Henderson’s case, he seems to be impressing the right people. George Garcia has been his boxing coach for the last four years, and he’s trained everyone from MMA fighters to Olympic-caliber boxers. “When [Henderson] was just starting, he’d say, ‘I’m really tired, I’m burned out, but I don’t care, we’re going to work.’ That’s something I don’t hear from a lot of people,” Garcia said.

During last December’s trip to South Korea, Henderson visited the facilities of Korean Top Team, the top Korean MMA team (natch), and spent some time training with Jung, the Korean Zombie.

“At first we didn’t go hard, but eventually Henderson wanted to up the training. I could only say to myself, ‘This is a true champion level fighter,’” Jung told the Korean press at the time. A few months and a vicious upkick later, Henderson would prove the Zombie right.

Henderson’s next fight is an Aug. 11 rematch against Edgar, and camp started in June for Henderson. Fighters are famously mum about their approaches to training and strategy, but Garcia, who seems never to have seen a fighter he couldn’t figure out, offered his analysis of the first fight between Henderson and Edgar.

“I knew that would be an easy fight for him,” he said of the first Edgar match. “Ben is a southpaw and [Edgar] is a right-hander. I have Ben go away from the right hand, usually. But I had him go toward the right hand, take away the right hand.” Henderson won the fight, and Edgar’s face looked like a mess early. Garcia added, excitedly, that the strategy for the rematch would be very different. The pre-match gamesmanship had clearly begun.

The press conference for the second fight was held on June 12, and humility ruled the day. Henderson and Edgar are two classic “good for the sport” guys, too earnest to unabashedly boast. One questioner goaded the champ by reading back a quote where Henderson had supposedly said he could beat Edgar 10 out of 10 times. Henderson corrected the questioner, saying that he had said he would train so he could beat him 10 out of 10 times.

Athletes of all stripes famously have trouble retiring, but Henderson already doesn’t plan on fighting far into his 30s. He’s trying to set himself up now through his work, but he knows that a lot of his opportunities in the future will depend on how great of a champ he becomes.

So he talked at the press conference about aiming for a longer win streak than Anderson Silva’s UFC record of 14 consecutive wins and 9 title defenses. He talked about being considered the best pound-for-pound fighter ever. He talked about training, and he talked about enjoying the moment, being pleasantly surprised to be recognized on the street. When asked if he had any predictions for how the fight would turn out, he replied, “It’ll be fun to watch! Make sure you’re there! Tickets for the fight are on Tickethorse. Go get it!”

And everyone laughed. He is, after all, the champ.

–

For additional reading from MNET, Seungjun E’s MMA site:

Benson Henderson Profile

Chan-sung “The Korean Zombie” Profile

A prior version of this story referred to MMA fighter Anthony Pettis as a white American. He is of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent.

This article was published in the July 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the July 2012 KoreAm, click below.