You’re only a child when the world around you, and the people in it, freezes. Seconds turn into days, then months, then years — and all the while, you’re aging while they’re not.

This is the story told in “Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned,” the sci-fi fantasy effort by South Korean director Uhm Tae-hwa that screened at the New York Asian Film Festival in July. The pic is led by Kang Dong-won, who picked up the Star Asia Award at the festival.

In “Vanishing Time,” two new friends, Su-rin (Shin Eun-soo) and Sung-min (Kang), have a bond forged by their shared understanding of loneliness. One day, they’re exploring a cave with two friends when they come across a mysterious glowing egg, which turns out to be a magical item that traps children in a frozen world where only they age. The boys vanish, leaving Su-rin behind. When one of the boys turns up dead, and Sung-min returns as a twentysomething adult, Su-rin — still 14 years old — finds the responsibility of protecting her friend thrust onto her shoulders.

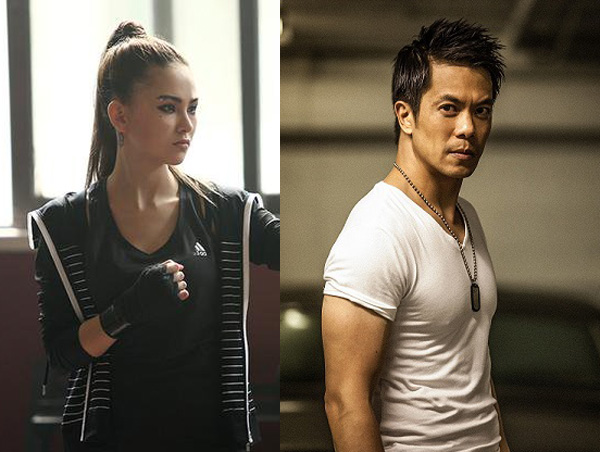

Shin Eun-soo and Kang Dong-won in “Vanishing Time” (Courtesy photo)

Fans of South Korean cinema are surely familiar with Kang’s work on the big screen, whether it be as a young priest bent on exorcising an evil spirit in “The Priests,” as the charismatic wizard Jeon Woochi in the film of the same name, or as the heart-achingly sweet Jung Tae-sung in “Temptation of Wolves.”

While it was Kang’s portrayal of a cerebral cop in “Master” and that of a crafty conman in “A Violent Prosecutor” that landed both films on last year’s list of South Korea’s Top 10 highest-grossing pics, we have never quite seen the actor as we do in “Vanishing Time,” as innocence in an adult’s body. “I have the type of personality where I get tired of things easily,” Kang said. “I hate doing things I’ve already done. It’s not fun. So this character [Sung-min] felt very fresh to me.”

NYAFF, which saw its 16th annual run screening 57 films this year, brings cinema in a range of genres from across the Asian continent to New York City.

“I feel almost a sense of duty, as a Korean actor and as an Asian actor, for being here [at NYAFF],” Kang said. “As more and more people become interested in our culture, they’re looking to our movies. I was surprised to see that at Cannes this year. Aside from whether it’s Korean films or not, I think it’s the same for everyone who is a creator. I want to work in collaboration with more people, and hopefully be able to meet with more audiences in America and in Europe.”

“Vanishing Time” was one of a handful of NYAFF’s Korean selections this year, and saw a limited theatrical release across the U.S. last winter, one of a growing number of films to hit North America from the increasingly influential chungmuro. At the same time, Hollywood has seen a trickling of Korean directors helming its projects, from Bong Joon-ho (whose latest U.S.-South Korea co-production, “Okja,” debuted on Netflix to much fanfare) to Park Chan-wook (“Stoker”) and Kim Ji-woon (“The Last Stand”). The same goes for a handful of Korea’s top stars, like Lee Byung-hun (“The Magnificent Seven”) and Bae Doo-na (“Sense8”), who have successfully transitioned to Hollywood.

The question is whether Kang sees himself joining in. “Whether it’s America or anywhere else, if I have the chance to work with talented people, I am up for the challenge,” he said. “I’m always open to anything. If they tell me to come to Africa, I will.”

“Vanishing Time: A Boy Who Returned” (Courtesy photo)

He’s a supporter of the emergence of more diverse platforms, namely digital streaming services like Netflix and Amazon that are gearing up to transform into serious studio contenders, on which filmmakers can create and show their work.

“A few years ago, I attempted to produce a film outside the existing system with my friends. That project didn’t work out, and we eventually had to fold it in its beginning stages. But we tried,” he said. “So I’ve readily accepted Netflix and new platforms. As creators, as long as we can make great films, we’re interested. And if we can make them in diverse genres, and have the flexibility to create what we’d like, even 4- or 5-hour films, that’s great.”

In Kang’s eyes, the expansion of Korean cinema onto the world stage has come organically. “This is an era in which it’s easy to learn about foreign cultures,” he said. “I think everyone is having an easier time of picking up global projects. I myself have been planning diverse projects with diverse people as well. Something is bound to happen, don’t you think? Soon.”