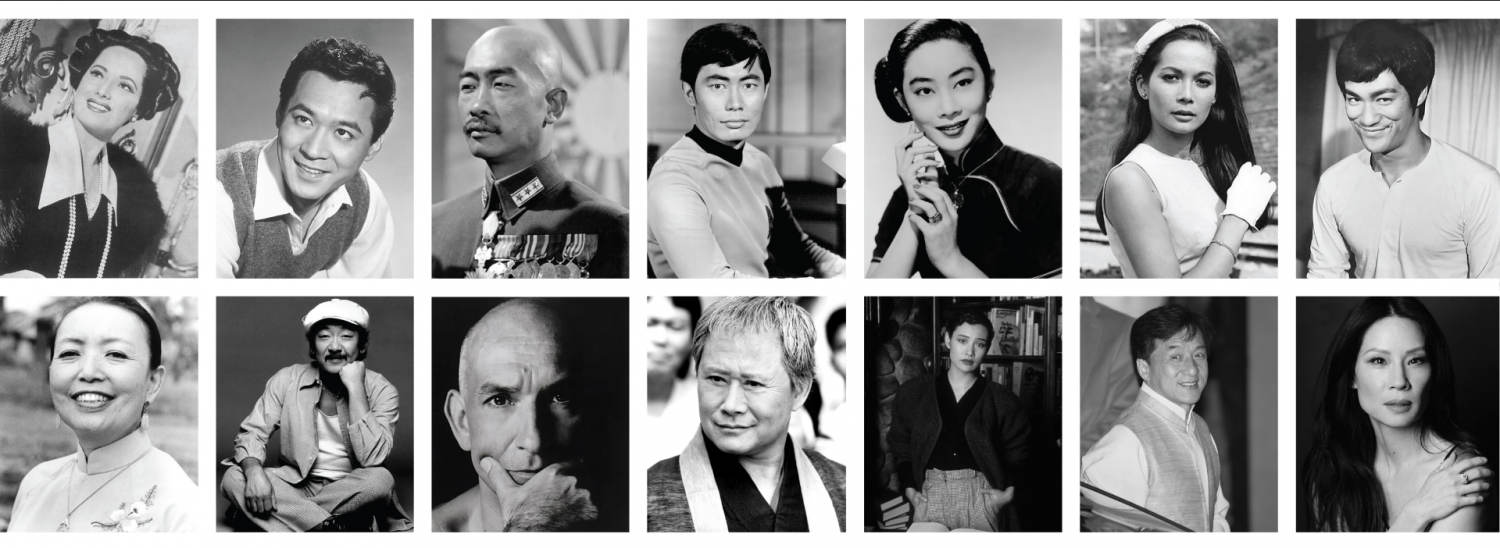

They played prostitutes, maids, butlers, laundry workers and craven villains. They were often denied substantive roles, equal pay and fair representation. Yet, they persevered.

This Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, we pay tribute to the actors and actresses who endured untold prejudice and discrimination to practice their theatrical crafts. The early pioneers gave way to subsequent generations, who would go on to expand roles and explore more vivid story arcs. Though this timeline could have been pages longer, we decided to end with Lucy Liu, a benchmark in the dramatic rise of Asian American representation during the 20th century, and before our numbers truly start to skyrocket at the advent of the millennia (and that’s even before counting “Crazy Rich Asians”).

We’re the first to admit that this list is by no means definitive. But at least it’s a start. Follow the actors to see how our representation and diversity evolved.

Sessue Hayakawa

Known as the first (of many) Asian American cinematic heartthrobs, Hayakawa began his acting career during the 1910s, in the silent era. Hayakawa rapidly gained a reputation—and a devoted female fanbase—in Hollywood for his portrayals of romantic, often dangerously seductive, male characters. In 1918, the actor formed his own company, Hayworth Pictures, to produce and star in his own creative works, often alongside his wife, actress Tsuru Aoki. Although rising anti-Asian sentiment forced Hayakawa to seek roles in Europe at the start of World War II, he eventually returned to Hollywood to appear in some of his most popular films, including “The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957). He is famously quoted as saying: “My one ambition is to play a hero.” It’s a goal still shared by Asian American actors today.

Anna May Wong

Despite Wong’s popularity and acting talent, she was repeatedly passed over for leading roles and cast as slaves and maids, to her frustration. MGM famously rejected Wong for the role of O-Lan in “The Good Earth” (1937), despite her publicized interest in playing the character. Citing anti-miscegenation laws that prohibited Wong from appearing opposite a white male star, the studio instead offered Wong the role of Lotus Flower, a villainous concubine who later becomes the main character’s deceitful second wife. Wong declined, saying: “You’re asking me—with Chinese blood—to do the only unsympathetic role in the picture, featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters.”

Merle Oberon

Often described as Hollywood’s first Indian actress, Oberon got her start in film by pretending that she wasn’t. Born in India to a Sri Lankan mother, Oberon concealed her true origins and claimed she was born in Tasmania to Anglo parents. Because she was white-passing, she was able to play coveted leading lady roles denied to the likes of Anna May Wong. Over the span of her almost 50-year career, Oberon had an on-and-off relationship with John Wayne (yes, that John Wayne), and starred in films like “Wuthering Heights” (1939) and “The Dark Angel” (1935), for which she earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress.

Jadin Wong

Wong defied the expectations of a meek and demure Asian woman from the very beginning. After running away from home to pursue a career in entertainment, she danced burlesque at San Francisco’s infamous Forbidden City nightclub in the 1930s, and entertained American troops overseas during World War II. After returning to America, Wong transitioned to the comedy scene, and once claimed to have gotten a gig by telling a booker “F-ck you!” when he asked her to say something funny. Wong would frequently appear in cabarets and on Broadway. In the 1970s, she formed Jadin Wong Management, a highly successful talent agency dedicated to promoting Asian American talent.

Keye Luke

Born in Guangzhou, Luke grew up in Seattle and moved into show business by painting murals and film posters during the early 1930s. He first appeared in “The Painted Veil” (1934) in a minor role, but the following year Luke landed his first major part playing Charlie Chan’s son in “Charlie Chan in Paris” (1935). Producers were so impressed by Luke’s skill and work ethic that they made the son a recurring character throughout the series. From there, Luke went on to act in a wide variety of projects that included “The Green Hornet” serials (as the original Kato) and “Phantom of Chinatown” (1940). He was also a founding member of the Screen Actors Guild. Readers might recognize Luke from the classic “Gremlins” films, as the mysterious Chinatown shop owner who sells the ‘mogwai’ that eventually cause so much trouble.

Philip Ahn

Korean American Ahn played dozens of Chinese and Japanese characters over the course of his career, becoming one of the most well-known Asian American actors of his day. Like most of his Asian American contemporaries, Ahn played mostly typecast or small roles, often a kind or goofy character—except during World War II. In the 1940s, Ahn played Japanese villains in several American war films, including “Back to Bataan” (1945). He received a number of death threats, but continued working in film and television well through the 1970s, appearing on TV shows like “Hawaii Five-O” and “Kung Fu.” His perseverance and versatility made him the first Korean American actor to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Richard Loo

After the stock market crash of 1929, Loo moved from a career in business to a career in film and theater. A risky decision to say the least, but the Chinese American actor made it work (as did his wife, Bessie Loo). He initially took small, often uncredited roles in silent films, but during World War II, his career took off. At a time when many Asian American actors were struggling to find work, Loo leaned into the prevailing sentiment and took on the parts of villains, primarily Japanese spies or commanders in American movies like “The Purple Heart” (1944) and “God is My Co-Pilot” (1945). According to his daughter Beverly, Loo did not mind playing these stereotypes, and in fact actually enjoyed them. “He felt very patriotic about being in those movies,” Beverly told the “New York Times” upon her father’s death.

James Shigeta

During the Korean War, Shigeta, already a well-known vocal performer, enlisted in the U.S. Marines and was set to be deployed to Korea. Instead Shigeta wound up in Tokyo and was signed onto the entertainment division of Toho Studios, who turned him into an overnight musical star. The “Frank Sinatra of Japan” eventually returned to America and went on to appear in several films as the romantic hero, such as Detective Joe Kujaku in “The Crimson Kimono” (1959). Shigeta also didn’t leave behind his musical background—he later played the lead in the film version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Flower Drum Song” (1961). In perhaps his most recognized role, Shigeta appeared as the heroic Joe Takagi, president of Nakatomi, in the 1988 action classic “Die Hard.”

Miyoshi Umeki

Umeki often played submissive, gentle women in supporting film roles, but within the boundaries of these stereotypes she managed to make quite a name for herself. The Japanese actress secured an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Katsumi in “Sayonara” (1957). Umeki’s Oscar was the first for an Asian woman, and as of 2019, she remains the only Asian American woman to win an Oscar for acting.

George Takei

Beloved actor Takei is well known for playing helmsman Hikaru Sulu on the original “Star Trek” series on NBC (1966-1969), a significant step forward in Asian representation during the time, but Takei had to overcome major obstacles to reach the USS Enterprise. His childhood included a stint in a Japanese internment camp in California during World War II, a foundational experience that he says helped develop his strong stance on social justice. After “Star Trek,” Takei continued to work in film, and developed and starred in “Allegiance” (published in 2012), a highly successful musical production inspired by his family’s internment. Today, Takei is an outspoken activist and serves on the board of East West Players and the Japanese American National Museum.

Lisa Lu

As a teenager, Lu performed kunqu, a type of Chinese opera, before moving to America and starting a professional acting career that now spans six decades. In Hollywood, Lu gained a reputation for her tenacity when pursuing parts, as well as incredible acting versatility. Her past roles include a nun, a gambler and an empress (on three separate occasions), and she’s won three Golden Horse Awards, the Chinese equivalent of an Academy Award. Time hasn’t slowed Lu down. In 1993 she starred in the influential “The Joy Luck Club,” recently played a major role in 2018’s “Crazy Rich Asians,” and even at 92 remains an outspoken supporter of Asian Americans in film.

James Hong

Hong’s acting career had an unlikely start: entertaining his fellow National Guardsmen during his time in the U.S. Army. His talents not only prevented his deployment during the Korean War (Hong stayed in America at Camp Rucker, putting on shows), but also launched a filmography that includes roles on “The X-Files” and “Seinfeld.” Though he already has several hundred credits to his name, including the laser-eyed David Lo Pan in “Big Trouble in Little China” (1986), Hong continues to appear in film and television, and is a strong advocate for Asian Americans in entertainment.

Nancy Kwan

Eurasian actress Kwan had no prior film experience before starring in “The World of Suzie Wong” (1960), but her performance earned her a Golden Globe award and launched her into international fame. In both film and magazines, from the U.S. to Europe, Kwan was portrayed as exotic and magnetically seductive. She even sparked a new women’s hairstyle trend with her short bob, known as “The Kwan.” She went on to appear in several dozen film and television roles over the course of her 50-year (and counting) career.

Bruce Lee

Lee is perhaps the single most iconic martial arts actor in the history of Western film. His father, a famed Cantonese opera star, introduced Lee to show business early on (in fact, he appeared in Esther Eng’s “Golden Gate Girl” as an infant), and he appeared in over a dozen films before he turned 18. As an adult, Lee traveled to America planning to pursue a career in martial arts, but instead landed his first major Hollywood role: Kato, in the popular superhero television show “The Green Hornet.” Lee went on to star in blockbusters like “Fist of Fury” (1972) and “The Way of the Dragon” (1972), which he also directed and wrote. Tragically, Lee died in 1973 a mere month before the release of his highly successful “Enter the Dragon,” which is now a martial arts classic. Lee’s legacy and influence has lasted far beyond his death. The period drama “Warrior,” overseen by Lee’s daughter Shannon for Cinemax, is based on an original concept that Lee developed and wrote.

Kiều Chinh

Chinh’s prolific acting career began in 1950s Vietnam, where she played parts in both Vietnamese and Western movies. She appeared in several American films, including “Operation CIA” (1965) opposite Burt Reynolds, and produced a war epic in 1971 titled “Người Tình Không Chân Dung” (Warrior, Who Are You). After the fall of Saigon in 1975, Chinh moved to America (sponsored by Tippi Hedren, no less) and continued her film career in Hollywood, eventually starring as Suyuan Woo in “The Joy Luck Club” (1993).

Beulah Quo

Quo (originally spelled Kwoh) didn’t get her start in acting until her 30s, and often played unnamed or minor roles in film and television, including the maid in “Chinatown” (1974). But Quo’s influence on Asian American culture, and on American culture as a whole, far surpasses her filmography. In 1965, Quo co-founded the famed East West Players, the first Asian American repertory theater in the country that continues to give API creatives a welcome place to tell their stories. Throughout her lifetime, Quo remained heavily involved with Asian American politics and was a strong advocate for more diverse and significant roles for Asians in entertainment.

Pat Morita

Morita’s filmography is pages long, but he’s best known for playing Mr. Miyagi in “The Karate Kid” films. His portrayal of the sage karate master garnered Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations, and elevated him into a pop culture icon. His work in television, though lesser-known, helped pave the way for future generations of Asian actors. Morita had recurring roles on popular TV shows like “Sanford and Son” (as Ah Chew/ Colonel Hiakowa) and “Happy Days” (as diner owner Matsuo “Arnold” Takahashi). In 1976 he starred in “Mr. T and Tina,” and played the titular lieutenant on police drama “Ohara” from 1987 to 1988. These shows were (and still are) some of the very few television programs featuring an Asian male lead.

Soon-Tek Oh

Over the course of several decades, Oh acted on Broadway and appeared in the Bond film “The Man with the Golden Gun” (1974) and voiced the father in “Mulan” (1998), to name just a few of his roles. Off-screen, Oh was a vocal supporter for Asian Americans in entertainment. He co-founded East West Players alongside Beulah Quo and also created the Lodestone Theatre Ensemble. Like East West, Lodestone was a crucial organization dedicated to promoting Asian American entertainers of the time.

Sir Ben Kingsley

Kingsley was born Krishna Bhanji, but began going by his stage name when he decided to pursue a professional acting career, concerned that his ethnic name might damage his chances of finding work. Under the new name, Kingsley transitioned from stage to film and television in the 1970s. His portrayal of Mahatma Gandhi in the 1983 film “Gandhi” not only earned him international fame, but also secured him an Academy Award for Best Actor (the first nomination and win for an Asian man) and a Golden Globe. Today, Kingsley is well-known for a thousand-yard stare that lends itself to villainous roles, including that of Trevor Slattery in “Iron Man 3” (2013).

Jet Li

Like Bruce Lee, Li’s acting career was born from his martial arts prowess. He starred in several Chinese and Hong Kong action films, including “Shaolin Temple” (1982), and in 1998 broke into Hollywood with “Lethal Weapon 4.” With its success, the international fame he achieved for his fighting and acting talents finally translated to the West. He announced his retirement from martial arts with his wushu epic “Fearless” (2006), but has continued to appear in American and Chinese productions over the past decade, and will even play the Emperor in Disney’s live-action “Mulan” (2020).

Joan Chen

Already a cherished teen acting prodigy in China, Chen moved to America in her early 20s to study film, later landing at California State University, Northridge. She played a number of minor characters in American film, including an unnamed appearance in Wayne Wang’s critically acclaimed “Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart” (1985), before gaining widespread attention for Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor” (1987), in which Chen played the Emperor’s unfortunate first wife. In 1990, Chen first appeared in one of her best known roles as mill owner Josie Packard in “Twin Peaks” and acted in popular Chinese and American films, such as “Americanese” (2006) and “Lust, Caution” (2007).

Jackie Chan

Known today as one of the world’s most prolific martial arts actors, Chan started his film career in stunt work and took on minor roles in Bruce Lee’s “Fist of Fury” (1972) and “Enter the Dragon” (1973). He became a monumental star in Hong Kong during the 1970s, as he incorporated comedy into his fight scenes, and Hollywood came calling with roles in “Battle Creek Brawl” (1980) and “The Cannonball Run” (1981). When those failed to take off, Hollywood producers ignored him until the 1990s, when Chan was offered several villain roles that he turned down to avoid future typecasting (including that of Simon Phoenix in Sylvester Stallone’s “Demolition Man”). The move paid off, and Chan went on to star in successful action comedies like the “Rush Hour” series and “Shanghai Noon.” He eventually started his own film production company, JCE Movies Limited, after expressing frustration with Hollywood’s limited possibilities for Asian American talent.

Lucy Liu

Liu, who initially struggled to find meaningful parts in Hollywood, made her television breakthrough playing cold and calculating Ling Woo in the legal dramedy “Ally McBeal,” debuting in its second season in 1998. Although many saw Ling Woo as just another Orientalist fantasy about exotic, seductive Asian “dragon women,” Liu’s role was nonetheless groundbreaking for API representation. Hardly any other Asian American faces were seen (let alone shown making out with the female main character) on television at the time.

Things have only gotten better for Liu since Ling Woo’s liaisons on “Ally McBeal.” In 2000, Liu became the first Asian American woman to host “Saturday Night Live,” the same year she starred in her first “Charlie’s Angels” film. Years after her delightfully vicious role as O-Ren Ishii in “Kill Bill: Vol. 1” (2003), Liu remains one of the most acclaimed Asian American women in TV and film, and has even been named a UNICEF ambassador. Right now, she’s creating art, working on her own project, “Unsung Heroes,” an anthology series focused on the unrecognized women who changed history—including Anna May Wong, and just received her own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

This article appeared in Character Media’s May 2019 issue. Subscribe here.