In an effort to encourage more young Asian Americans and their families to open up about mental health and depression, filmmaker Eric Lu partnered with the Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds and the Massachusetts General Hospital to produce “Looking for Luke.”

The short documentary focuses on Luke Tang, a Harvard sophomore whose suicide left his family and friends shocked and eager to help others like him.

“Looking for Luke” paints a picture of Tang’s life by sitting down and conversing with those who knew the Harvard sophomore best: roommates, childhood friends and his mother and father. Tang’s loved ones described him as intelligent, goofy and insatiably curious. He was the last person they expected would harbor suicidal thoughts. The suddenness of his death and his family’s ignorance of his struggles highlights a problem that runs rampant in the Asian American community — namely, the silence and stigma that surrounds mental health and depression.

Studies have shown that Asian American college students have higher rates of suicidal thoughts than their peers and are often discouraged from seeking help or talking about their struggles because of cultural stigma.

Lu said he hopes that the openness of Tang’s family and friends will give others strength to do the same.

What was your motivation for making a documentary that tackles such a difficult topic to talk about?

[One] thing that drove me is that because talking about [mental health and depression in the Asian American community] is hard and so sensitive, a lot of people shy away from it. There’s a lot of stigma. There’s a lot of shame. A big part of my desire was to shine a light on it. I think there’s a lot of anxiety surrounding it. That was my main motivation.

Your documentary tackles some heavy themes such as suicide and depression. How did you go about handling the sensitive material and were there any challenges to it?

The main thing was being able to form strong relationships with Luke’s friends and family. Because it was so sensitive, a lot of it required having a lot of conversations before I started shooting. I think because I spent about three or four months before shooting actually building that relationship, because I was able to have these conversations beforehand, I built up a lot of trust. Another thing, too, is that I also went through a period of depression so I could empathize [with them]. I came from a very open and understanding place.

Luke’s parents, Wendell and Christina (“Looking For Luke”)

One of the things that struck me the most about “Looking for Luke” was the openness of Luke’s parents. Can you talk a little about that?

When I first called Luke’s parents, I had no idea what they were going to say. This was only six months after his suicide, so I was freaked out that they weren’t going to want to have anything to do with this. But surprisingly, they were very, very open. After the call, they said, “Come on over to New Orleans, film us, we’re open to doing the interview.” They wanted to be able to tell Luke’s story so they could help other parents. Although it was a very difficult topic, I think there was also a layer of hope and optimism that came from the parents wanting to use this most painful experience of their lives as a way to help others. Yes, this is really painful, but at the end of the day, we want to use this to save lives.

This film was produced in partnership with the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds. How did that partnership develop?

It goes back to medical school. I was in my third year and one of my mentors was the founder and director of the Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds. He had told me about what the organization was doing. They wanted to be able to use multimedia to provide educational materials about mental health in kids and adolescents. When I decided not to do residency and do filmmaking, I was talking to my mentor and he said, “Hey, we’d like to be able to make films about this issue.” Around the same time, Juliana Chen [the pic’s executive producer] wanted to make a film about Asian American mental health. It all just worked out perfectly, timing-wise. She approached me and together, we just started making this film.

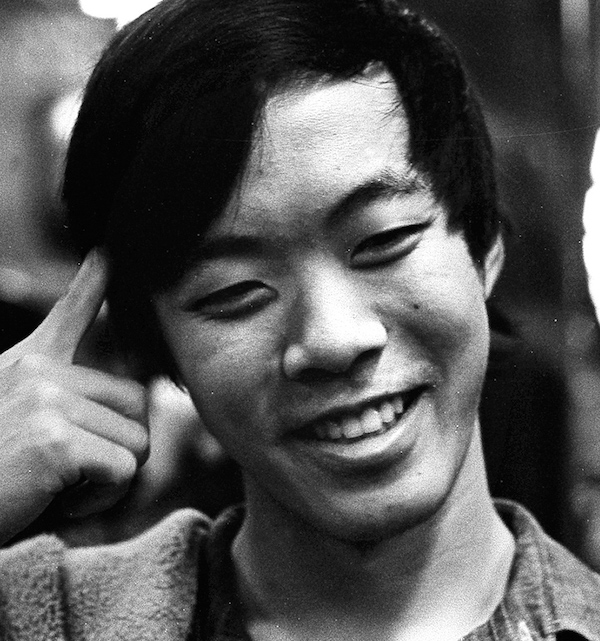

Luke at his high school graduation. (“Looking For Luke”)

Have you been able to gauge audiences’ reactions to your documentary?

There’ve been a few screenings at Harvard and at Luke’s church in Boston. Those have been really emotional. The audience members, some were people who knew Luke, his friends, his mentors. I think at every screening, people have really responded to the film and, like you, have been touched and moved by the parents, who are so open. I was pretty shocked, actually. I didn’t expect them to be so open, and a big part of that was because they wanted to help the youth and other parents with their story.

What has been the most powerful part of making and screening this film?

I think one of the most powerful parts of the screenings are the discussions that happen afterward. They last between two to three hours, and people stay around for that long because the film really opens up a space for people to have conversations that they wouldn’t have on a regular basis. I think because these are not things we discuss very openly in public, there are a lot of questions. Because of the stigma and shame, people don’t want to really bring it up, especially within the Asian American community, where often depression is seen as a weakness rather than a real thing. People don’t want to be labeled as having depression, and as a result, people don’t want to talk about it.

At these screenings, because Luke’s parents open up about where they’re at, and because of their honesty and their vulnerability, it gives permission to people [to do the same]. We screen this for the parents, too, and it’s always very interesting because they want to know how to talk to their children about mental health, but they don’t even know how to begin talking to their teenaged children, whom they feel like are struggling. They don’t have the vocabulary or sensitivity or experience in terms of talking with their children about it. At these screenings, we have clinicians, psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health experts to be able to guide people and provide insight and advice.

For more information about the film and upcoming screenings, check out the website at lookingforlukefilm.com.