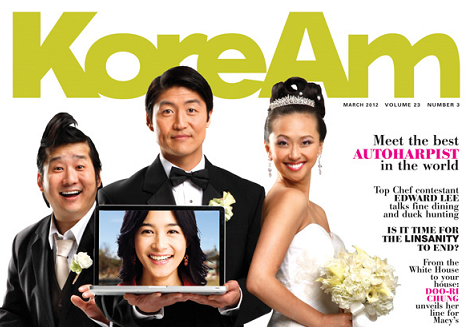

Ray Choi is the best autoharpist in the world. Yes, autoharp.

story by Eugene Yi

photographs by Luke Inki Cho

My fifth-grade classroom, like so many across the country, had an autoharp. It accompanied the patriotic song sung every morning after the Pledge of Allegiance. A different child would play it every morning until everyone had rotated through, at which point we would rotate through again. The player was guided only by a sheet of paper with the lyrics of, say, “This Land is Your Land,” with the letters of chords written over the word where the change should happen. Chords were played by pushing the button that had the letter of the chord engraved on it. Push, strum, push, strum. No one practiced the autoharp. No one needed to. The instrument was, literally, child’s play. Is it any wonder the instrument was once sold door-to-door, for easy use in home parlors by non-musicians? Or that the rise of the phonograph led to its demise?

Perhaps because of its apparent ease of use, the autoharp seems to actively discourage virtuosity. Its 36 strings are arrayed tightly under the buttons for ease of pressing and strumming. Very skilled players can pluck melodies out, but few achieve this level of skill. As the instrument fell into disuse after a brief folk revival in the ’60s, autoharp playing and technique might have stayed the way it was, preserved in amber, until a Southern Californian music store owner named Ray Choi smashed notions of what an autoharp could do. His friend, Bill Meis, a writer and fellow autoharp enthusiast, said, “You can say without exaggeration that this is extremely unique.”

On a recent day in the Orange County suburb of Garden Grove, Calif., Choi demonstrated his innovative autoharp technique in the music shop he’s run since 1991, Grace Music and Violin. String instruments of all sorts hang from the walls, and by the register, Choi hawks a small box of his CDs recorded by his son, David Choi, the YouTube star. But the active areas of the store, the counters and the floors, are lined with autoharps; some for repairs, some being built (he is a luthier), some for sale. Choi is a genial man with a large, friendly face, but when he shakes hands, one is immediately struck by their size. He has small, strong hands, nimble and seemingly a good match for the autoharp’ s unforgiving proportions.

Choi remembers when he decided to become a musician. At 9, he won a singing contest in his hometown of Chungju, South Korea, and his life’s path was set. His tastes, though, veered away from popular music and he fell hard for traditional music. Particularly yodeling.

“It was very unusual. Nobody was interested in traditional music like me,” he said.

But like so many of his generation, he felt trapped in dictator Park Chung-hee’s South Korea. So he left the country. Once in the States in the 1980s, Choi did what most Korean immigrants did: he worked, he saved, and he went to church.

Choi naturally fell into a musical role at his church, which had an autoharp. The instrument was not uncommon in many Korean churches at the time (again, for its ease of use). He took to the instrument as an outlet for his talents, and it clicked with his love of traditional folk music.

“The autoharp is really good,” he said, simply, his eyes shining.

Choi soon became something of an evangelist for the instrument. Once he’d saved up enough money to open up his music store in 1991, he started selling autoharps to other Korean churches. So many that he became the No. 1 seller of autoharps in the country, meriting a visit from a quizzical representative of Oscar Schmidt, the last extant manufacturer of autoharps. He also started making them himself, hoping to tweak the instrument more to his liking, and engraving elaborate patterns along the edges.

“Nobody makes autoharps like Ray does,” his friend Meis said.

At this point, Choi thought he was pretty good at the instrument, to the point that he decided to make a commitment to it, he said.

“I decided to be an autoharp champion,” he said.

He went to the International Autoharp contest in Walnut Valley, Kansas. And he didn’t even place. The autoharp, with its promise of ease, had fooled him.

Choi started practicing, up to 10 hours a day. Thumb leads, plucking, timing the pressing of buttons to dampen certain strings right after he played them to isolate melodies. The average night would have him on the sofa, practicing the autoharp, driving his family crazy.

“[My wife] she extremely—” he said, pausing to find the right words. “Complain. Stress. I was crazy. Too

much practice.”

But it was that practice that led him to ponder ways to expand his technique. “I had a question in my mind all the time. Autoharp technique, there is basically picking and strum, that’s all,” he said. No one had really invented a new way of playing the instrument in decades.

“But five years ago, one night, I was just on my sofa and playing, same as usual, [I said], ‘Oh, let me try tremolo.’”

The tremolo is a difficult classical guitar technique where the player uses all non-thumb fingers to pluck repetitions of a note after it is initially played. The rapid repetitions give Spanish classical guitar, and some mandolin playing, its studded, lilting lyricism. Though some players had attempted tremolo on the autoharp, Choi said he didn’t like the way they approximated the technique. It just sounded like broad strumming to him, with none of the precision of the tremolo.

“So I tried little by little, back and forth,” he said, demonstrating, playing one string with two fingers, again and again, his voice rising as he got swept up in relating the thrill of discovery. “[I thought] ‘Oh, this is good!’ It was so exciting at the time. I thought, ‘It’s possible. Wow, this is possible.’”

Choi set out to master the tremolo, practicing even on his 25-minute commute from his home in Fullerton to the store in Garden Grove, using the steering wheel as a string of sorts.

“Of course, wheel is much thicker than string,” he said, laughing. He gave his technique several names: the butterfly tremolo, the hummingbird tremolo, the Raymolo.

“You know, a hummingbird’s wings are so fast,” he said. “They flutter.” And the way he plays the tremolo on the autoharp, all of his fingers never stop fluttering. Each finger isolates on a string and plays it as fast as his hand can wave. It’s an astonishing torrent of notes.

By the time he felt ready to show the technique in public, he had been training for four years. In 2010, he went back to Walnut Valley confident he could win. And he nearly did. But the stresses of his technique, in competition, tore his fingerpicks apart. So he tried using his bare fingernails instead. They followed suit, and he placed a bloody third. The next year, he returned to the competition having practiced even harder and with a new weapon: artificial press-on nails. That year, he swept all of the major American autoharp competitions.

Choi is now enjoying a mandated victory lap; winners can’t compete again for three years. But each of the autoharp competitions is flying Choi out to teach seminars on his technique, and there’s been an uptick in students, wanting to learn from the champion.

Kate Lockhart, who said she’s close to 80 years old, drives up from Oceanside near San Diego once a month for her lesson with Choi. A long-time student of Choi’s, she first became interested in the instrument through 1960s musicians like Joan Baez.

“It’s such an honor to get lessons from him,” she said. “He’s very patient and tells me when I’m improving.”

Choi’s evangelizing for the instrument continues in the Korean community as well. He is working on a book of Korean hymns arranged for the autoharp, and he plans on going to Korea to distribute the book there, the conquering hero returning to his native land.

“I’m very excited about it,” he gushed.

He’s also working on an English-language book about the butterfly tremolo technique. There is the inevitable question, of course, of whether he is giving his secrets away.

“It took me five years to be able to do it,” he said, with a small smile. “So everybody else is five years behind.”

“He’ll probably invent something new by then,” Meis said, laughing.

This article was published in the March 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today!