Are We There Yet?

The third Harold and Kumar film has the titular characters grappling with adulthood. Has Asian American media itself come of age?

By Eugene Yi

So you’re watching TV. It’s good, it’s OK, it’s whatever. You have it on just to have something on. The situations and the characters are stock, and the jokes barely seem to fill the time between the imagined rimshots. You’re watching it and not watching it. It’s just TV, after all.

An Asian character walks onto the set. You think, “Oh. There’s one.”

You are counting. And you are primed for outrage.

Exotification? Emasculation? Model minority? A terrorist? A stupid accent? A deadly martial art? You think, “What am I going to be mad about now?” It’s not just TV, after all. A stock ethnic character on television is not just a caricature; it’s a template, and there are those who will overlay it on you, see where the lines overlap and where they don’t, and then, stereotype accordingly. Representation channeled through society influences identity—

Or does it? On the morrow of the release of A Very Harold and Kumar 3D Christmas, I’m spending a lot less time going all ethnic-studies on the film. In my lifetime, we’ve gone from “Whats-a happening-a, hot stuff?” to “MILF!” to, well, what exactly? Too many different representations, too many different actors, a fugue of voices upon voices striving to be heard. “Oh. There’s one” has become “OK, another one.”

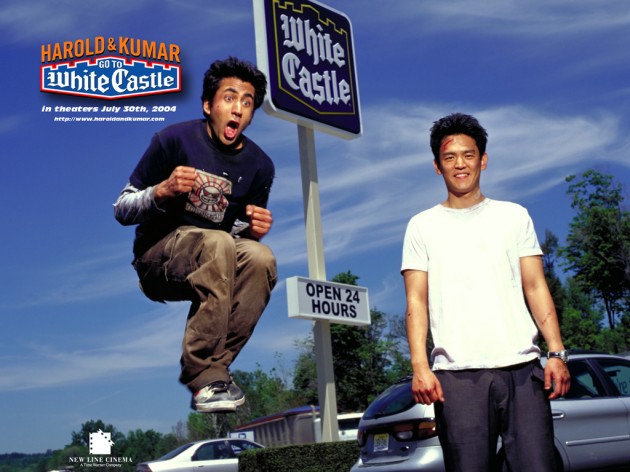

Would this have happened without Harold and Kumar? Perhaps. But it is still the first Asian American Hollywood franchise. “I consider it an achievement that one movie was made, another grand achievement that a second one was made, and completely implausible that a third one was made starring a Korean guy and an Indian guy as the leads,” said Harold, née John Cho.

[ad#graphic-square]

One could conceivably reverse the order: that it was completely implausible that one would get made, a grand achievement that a second one did, and a lesser but still notable achievement that we’re now at part three. And not just because the films made money. Something subtle has happened in the relationship between Asian America and mainstream culture. Seven years ago, when the first film came out, two Asian Americans helming a studio comedy seemed like the fruition of an impossible dream. Now, it’s hard to list prominent Asian American actors without feeling like you’re leaving someone notable out.

Some of the most popular YouTube channels are run by Asian Americans, telling stories about Asian Americans. Most large cities have at least one, if not several, Asian or Asian American film festivals. There is an array of options available for the average Asian American looking for faces that look like theirs. It’s not some utopian, Obaman post-racial nirvana, of course. But all the small steps—cultural, political, technological, accidental—seem to have allowed Asian American media to trend towards some sort of maturity.

The census data shows that Asian Americans make up about 5 percent of the population. If we are anywhere close to that, part of me starts to wonder: Is this pretty much how it’s going to be? Is this the beginning of the golden age of Asian American media? Or, bottom line: When Captain America has an Asian American in his gang, as he recently did, is it worth it to count anymore?

It’s been 14 years since a group of young filmmakers barnstormed the Asian American film circuit with stories that seemed to shrug off the concerns that had dominated the discourse to that point. Identity politics gave way to the surreal fairy tale of Justin Lin and Quentin Lin’s (no relation) Shopping for Fangs, or the youthful strivings of the teenagers in Chris Chan Lee’s Yellow.

The young Asian American audience that responded to these independent films had their ardor intensified in 2002 with the release of Justin Lin’s Better Luck Tomorrow. The most active (and activist) sought to channel this energy by organizing, with sites like Asianamericanfilm.com sending out weekly emails to remind Asian American moviegoers to vote with their dollars at the box office for any film with an Asian face in it. Cho happened to act in all three of the aforementioned films.

“Back then, people saw a revolution. I thought that was overstated,” said Cho. “I thought these are good movies, but I just didn’t see how the data backed that up. I saw the fervor in the Asian American cinematic community, and I just was baffled at the expectation placed on the shoulders of those movies. I thought it was unfair to those films.”

What filmmakers faced were the expectations of the ascendant second generation of Asian Americans, the ’70s and ’80s babies of the rush of immigrants from Asia following the loosening of the quota in 1965. And like any bulge in demographics, they came with demands.

“For 10 years, it seemed like every year, I was getting that question, ‘Things are about to change, right?’ I never felt that,” Cho said.

The first Harold and Kumar film was released in this environment, and was savvy enough to include a Better Luck Tomorrow reference early in the film. The writers, Jon Hurwitz and Hayden Schlossberg, wrote the ethnicities of the leads into the characters out of fear that a studio would change them, according to Kalpen Modi (Kal Penn’s real and pre-erred name).

The film went on to make only $24 million at the box office, but, helped along by the peak years of the DVD craze, made $60 million after it left the theaters. For an original investment of $9 million, not a bad return, and the door for sequels opened.

It’s staggering to think how much the world has changed since then. The notion of a film that finds a second life on DVD is no longer really valid. Facebook was still just a Harvard thing at that point. In the lightly fictionalized film The Social Network, 2004 would have fallen not too long after the tiki-themed college party where the leads muse on the mysterious alchemy between Asian girls and Jewish men. Something about how Asian girls could dance and Jewish boys couldn’t.

This scene would likely have drawn the unalloyed ire of 2004’s then-nascent Asian American blogosphere. But 2011’s blogosphere didn’t get angry. It noticed, it shrugged, it thought, “Well, I can show you Asian girls who can’t dance.” The tone was different. This, apparently, is how discussions about race happen now (at least when generalizations are made by madcap dialogue overwriters like Aaron Sorkin). What changed?

For Asian Americans, part of it just has to do with demographics.

“It wasn’t unusual when I was growing up, where you were the only Asian person in class,” said Oliver Wang, professor of sociology at California State University, Long Beach. For college students he comes into contact with today, however, “that’s really unusual,” he said. “Identity politics were really coming out of a very nationalistic response to feelings of racism and oppression—the sense of being under fire.”

Ten years ago, it was easy to find examples in the media that fostered this sense of oppression. Not just for Asian Americans; a “must-see TV” show like Friends, ostensibly set in New York City, featured monkeys but no people of color. Phil Yu, a.k.a. the Angry Asian Man, started his blog in 2001 partially to keep track of Asian Americans in television and film. Lucy Liu, and whoever the other one was.

“Because there were so few, it made every little one kind of a big deal to me. And now, and I can say this is a good thing, I can’t keep track of all them right now,” Yu said.

Modi sees a similar trend. “The kids who are in high school now don’t have to grow up with just Apu (from The Simpsons) … or brownface on Seinfeld. They see Aziz [Ansari on Parks and Recreation], they see Mindy [Kaling on The Office], they see John Cho. Literally, there’s no shortage of Asian Americans on TV.”

Wang added, “Especially as a father of a 6-year-old, who’ s coming into her own cultural consumption, it’s profound to me that she’s going to grow up in a vastly, vastly different media environment than what I did.”

Hollywood’s diversity numbers are usually pretty moribund, but the percentage of Asian Americans cast in TV shows and films has been slowly rising, from 2.1 percent in 1998 to 3.8 percent in 2008, the last year that data was made available, according to the Screen Actors Guild. Small numbers, to be sure, but inching upwards, closer to the presumptive goal of 5 percent.

“If the goal is to have an accurate reflection of the world we live in—and I don’t mean we need to have the exact same percentage in the census appear on screen—[there are] a lot of parts of the country [that] don’t look like the media we see,” said Adam Moore, interim national director of affirmative action and diversity for SAG.

And though 3.8 percent isn’t close to the non-goal of 5 percent, the way the roles break down is curious.

“We’re still not seeing a whole bunch of progress in feature film lead roles,” said Moore. “But you are seeing some things in the independent world and in supporting roles in television. There are strides being made, certainly.”

Numbers for Asian Americans in mainstream feature films have actually dropped, but television has more than made up for the difference. Just between 2005 and 2009, the number of Asian Americans on primetime television roughly doubled, from 17 to 33, according to the Asian American Justice Center, which puts out an annual diversity report card.

Some of this may have to do with the way the two industries are funded. Feature film relies increasingly on international markets, making the 3D CGI sequel-ready megacinema experience the bread and butter of the major studios. One imagines that, someday, an Asian American may emerge who can sell tickets in both Peoria and Beijing, but for now, the hegemony of explosions, robots and, usually, white actors rules.

Television, however, relies on advertising. And that’s where there’s been a shift. Asian Americans have more buying power than all but the four richest states, according to a 2007 study from the Selig Center for Economic Growth (the four richest being California, New York, Texas and Florida)—and this analysis was done before the jump in population measured in the 2010 census. And though “Asian America” is a notional financial entity at best, it’s the kind of stat that gives advertisers a target, and there has been an attendant rise in the number of Asians who appear in advertisements. If Korean American actor Randall Park is shilling K-Y sexual lubricant, well, something’s probably going right.

These numbers, though, don’t describe a broader shift in attitudes in mainstream culture. There seems to have been a normalizing of Asian faces. The Internet, cable television, the wealth of media now available have made it far more likely that the average American, as they consume their daily media, will run across an Asian person doing something mundane, buying a cell phone or watching a basketball game.

And the shift is slowly being incorporated into the way stories are told, according to Cho.

“There’s a generational turnover with writers [in Hollywood],” he noted. “I think there’s a different attitude about casting in the industry right now. Fingers crossed, it might stick.”

As an example, take Modi’s experience auditioning for his role on House. He said he auditioned against people of all different ages and ethnicities, both men and women, a post-racial, post-agist, post-sexual approach to casting that is more interested in a compelling performance than anything else.

Still, generalizations—positive or negative—about the state of Hollywood were downplayed by Modi, who stressed a nuanced, evidence-based approach to media representation when he taught a class about Asian Americans in the media at the University of Pennsylvania in 2008.

He emphasized the economics of the industry, having his students pore over box office numbers in addition to texts on theories of representation. Trying to decipher casting decisions, he argued, can be tricky.

“Oftentimes, the results [of a test screening of a show] might be bad, but the head of a network might show it to their kids, and they might like it,” he said. “There are so many different factors pushing and pulling. At the end of the day, there are opportunities and hindrances.

“The notion that Hollywood is a monolithic entity, where you can say, ‘Have things gotten better or not?’ ‘Is this as good as it gets?’ I understand the need, and frankly, look, if you asked me this 5 or 15 years ago, I would ask similar questions,” said Modi. “But I guess the reality is there is no monolithic Hollywood. To the extent that we accept that it is a monolith, it absolves us of the desire to really change it. And I don’t mean that through the context of social activism, which is great in its own right, but [for] the kids who are in high school … it doesn’t allow us to encourage these folks to become writers and tap into this art form in the political context.”

The increased numbers of Asian Americans in the entertainment industry have allowed media representations to begin to reflect the diversity of experiences that is Asian America. On the one hand, Harold and Kumar provided an Asian American gloss on the gross-out comedy. “Asian Americans … in a crazy balls-out comedy like that? You never really saw anything like that,” Yu, the Angry Asian Man, said. “And now, if you see comedy line-ups on TV, there’s lots of Asian American actors in comedy. I think it’s pretty interesting.”

On the other hand, conversations about stereotyping are refreshed. Ethnic stereotypes have a long history in comedy, of course. Some have decried actor Ken Jeong’s work for its reliance on stereotype. This type of conversation could’ve derailed Asian American support for an actor like Jeong just a few years ago, but today, there’s a different outcome.

“I get it, they’re tired of seeing his penis become a running gag,” said Wang, the professor, referencing Jeong’s infamous comedic stunts in the Hangover films. “But to me, Ken Jeong is just one person in a spectrum.”

The fact that this spectrum even exists is a sign that, in some ways, the old models of looking at Asian Americans in media no longer hold. It seemed like, at one point, perfection was demanded. Now, every role doesn’t need to depict Asian Americans as heroic, patriotic, brilliant, perfectly abbed and hot in the sack.

Modi received some criticism for his decision to play a terrorist on the Fox series 24. Especially in post-9/11 America, where one could imagine a generation of South Asian performers squandering their talent in roles like Terrorist No. 2, Modi’s was a fraught decision. And though he is sensitive to political concerns (he did work in the White House, after all), the actor said he took the part for the challenge of playing the character. A non-smoking vegetarian who has said he is afraid of guns, Modi called the role “a huge acting challenge. And anytime you’re doing something that’s personally uncomfortable, it’s a huge thing to do [as an artist].”

In a world where there is a spectrum of performers, this is the kind of decision that can be an individual performer’s choice, rather than some sort of proxy choice made on behalf of an entire demographic. It’s the kind of liberty that Margaret Cho didn’t have, when she was excoriated by the Asian American community for her former sitcom All-American Girl.

In a 2008 speech at KoreAm’s Unforgettable gala, upon accepting an award for his achievement as an actor, John Cho noted that he started acting when All-American Girl debuted on ABC. “She was our sole representative, our only image of ourselves to give to the outside world, and we didn’t like it so honest, so imperfect,” he said.

“But there is such a plurality of expression in our community today that this notion of representing seems suddenly archaic. And though I have always fancied myself forward thinking as it relates to my career—trying my best to avoid stereotypes and accents and such—I now know that that was an old way of thinking. Because I was always bound by what they thought. Because even to challenge the stereotype is to be enslaved by it.”

[ad#graphic-square]

Cho went on to talk about a new “physics of representation: one in which we are unburdened by identity, unobligated to explain who we are. Representation not by presentation, but by being.”

Three years after that speech, Cho seemed to affirm this view. “As a younger guy, I almost exclusively looked at the world and saw color, in every political situation, every artistic situation. And now that’s so much less than it used to be,” he said. “I think less about my collective identity with Asian Americans, because I have other collective identities. My group is my family, more than anything else. And everything else is extremely secondary.”

An article like this one demands an overarching and overgeneralizing historical framework, and Wang offered a pretty good one (the overarchingness and overgeneralizingness of which he fully admitted to, and which I will admit to further developing). Asian American artists in the ’70s lived in a besieged environment. America was still quite segregated, quite polarized and reeling from the ’60s. Conversations turned inward, with authenticity and allegiance often dominating the discourse (“Who are we, as Asian Americans?”). The artists in the ’80s and early ’90s grew out of this environment and saw infiltrating the media as an act of political, community-based activism (“We need to get our stories out!”).

An infrastructure developed to support that model (film festivals, organizations like Visual Communications in Los Angeles, and the National Asian American Telecommunications Association in San Francisco). This model supported a generation of artists who inherited, but did not struggle as mightily with, the same identity-based issues as their forebears. It allowed actors like Cho and Modi, and filmmakers like Justin Lin, to aim for, and attain, mainstream success.

“Making your voice heard, or getting representation— those battles have been fought,” said Wang. “Once you get past the ‘we just want to be visible,’ it’s a question of ‘now what?’”

The artists who have come of age in the Final Cut Pro era have provided at least the beginnings of an answer. The democratization of, well, everything, spurred by the technological advances of the past decade have allowed YouTube stars like KevJumba and Wong Fu Productions to be massively popular, and unapologetically Asian American. On screens of every size, we are given the chance to upend our own stereotypes.

“It’s kind of sneaky and funny that a stoner movie is the thing that’s probably, in mainstream media, gone the farthest with Asians,” Cho said.

This, of course, just puts Harold and Kumar in the long- standing American tradition of counter-stereotypical comedies like The Cosby Show.

The sitcom played against the prevailing racial stereotypes of its times, presenting the bourgeoisie Huxtables as a counter- point to the Superflys and Shafts who had dominated cinematic African America. The show was part of a wave of African American culture that swept the mainstream during the ’80s, from Eddie Murphy to Vanessa Williams to Michael Jordan to Oprah Winfrey. MTV, back when it played music videos, didn’t play anything by a black artist until Michael Jackson.

The fact that it happened in the ’80s, a generation after the Civil Rights Movement, cannot be ignored. This was the coming of age of the first generation of African Americans, young enough to see the possibilities after the end of Jim Crow America.

And it’s easy to see a similar phenomenon these days as a wave of Asian American culture sweeps through the main- stream, from the Far East Movement to Tiger Moms to the Harold and Kumar trilogy. The timing also, of course, can’t be ignored. This is the coming of age of the first generation of Asian Americans, born here and fluent in the culture, that has the numbers to move mass culture.

And just as Cosby complicated the conversation about African American identity, our conversations are becoming more complicated as well. In some ways, it’s a return to the original question: What is Asian American media? On the one hand, we have an actor like James Hong, who, be- cause of the generation he came up in, has built a career on playing stereotypical roles. On the other hand, we have a rap group like Das Racist, which manages the tricky balance of being both political and apolitical, racial and post-racial, progressive and regressive, all at once.

And of course, there are performers like Cho and Modi, who have managed to play up or play down their ethnicity, depending on the role, a complexity that popular media representations now encompass. And that feels like progress.

There is, of course, still fodder for righteous rage. Any Google search will turn up something that’ll make you shake your head. But there have been so many little surprises during the last 10 years. Who knew we were such good dancers? Who knew the Fast and Furious series would be a stealth Asian American showcase? Heck, who knew there’d be a third Harold and Kumar film?

This just might be the beginning of the golden age of Asian American media. All in all, it’s cause for hope.

Still, I probably won’t stop counting anytime soon.

This article was published in the November 2011 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today!

[ad#bottomad]