Who was the young, no-nonsense judicial powerhouse that played referee in the highly contentious Apple v. Samsung case? The answer may surprise you.

by SUEVON LEE

It was one of the most closely watched trials in federal court this year.

Iconic American brand Apple had accused South Korean electronics giant Samsung of stealing the design and technology of its iPhone and iPad for the latter’s Android-operated smartphone and tablet products. It was the kind of trial followed not only nationwide, but overseas for its significance on the explosive and very competitive smartphone market. However, with testimony marked by highly technical patent law jargon stretching over three weeks, it was also the kind of trial that could easily put courtroom watchers to sleep—the judge herself even asked the nine jurors at one point whether they needed caffeine.

Indeed, it would be the sharp tongue of the Honorable Lucy Koh who kept things crackling in the San Jose courtroom.

Just Google “Lucy Koh” and count the multiple hits that contain the phrase “smoking crack.” In what’s become her most quoted remark from the bench, Koh snapped at an Apple attorney facing a tight time frame, “Unless you’re smoking crack, you know these witnesses aren’t going to be called.” When Apple and Intel lawyers asserted that one of Samsung’s witnesses was legally not allowed to testify, Koh demanded, “I want papers. I don’t trust what any lawyer tells me in this courtroom.”

Her candid—and often colorful—comments in the midst of lengthy, dry courtroom proceedings inspired one blog to list “five of our favorite Koh smackdowns.”

Koh kept the trial moving along at a brisk pace, often urging the parties to reach a settlement. “It’s time for peace,” she declared late in the trial, Forbes reported. “If you could have your CEOs have one last conversation, I’d appreciate it.”

Obviously, that didn’t materialize—after a surprisingly quick three days of deliberations, the jury on Aug. 24 returned a verdict in Apple’s favor, issuing a smackdown of its own: a total $1.05 billion in damages against Samsung.

In a trial featuring two battling legal heavyweights, Koh did a standout job as referee, say those who followed the proceedings.

“There were big personalities in the room—lawyers who are paid princely sums to push hard for what’s in their client’s best interest,” said Brian J. Love, assistant professor of patent law and intellectual property at Santa Clara University School of Law. “Judge Koh recognized this and set strict, but fair, rules and didn’t budge. When lawyers tested her boundaries, she called them out.”

Who is this outspoken, no-nonsense judicial dynamo with the ready quip?

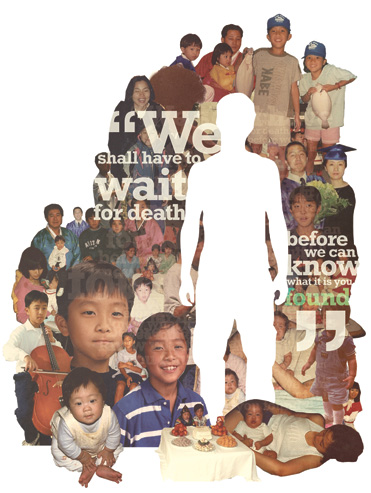

In short, she is a powerful symbol of the strides made on the federal bench when it comes to ethnic and minority representation—a testament to her hard work and achievement, but also her deep-rooted conviction in a more equal world.

As a young student at Harvard Law School in the early ’90s, Koh took part in a vigorous student-led push for more women and minority faculty hires. Those efforts played out on campus, in the courtroom, all the way to the law school dean’s office—marking a rocky but defining time in the school’s history.

Today, the one-time student activist is making history herself, as one of just two Korean Americans serving in the federal judiciary.

That’s not all: Appointed by President Obama in June 2010, Koh is the first-ever female Korean American federal district judge in the country. She’s also the first-ever Asian Pacific American district judge in the Northern District of California, a busy jurisdiction encompassing the tech-heavy areas of San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland—and where more than one-fifth of the state’s population resides.

At 44, Koh is on the young side for an Article III federal judge (those appointed for life, as opposed to a specific term). She’s one of just 17 active Asian Pacific American Article III judges among a total 874 in the country. (Think that first number’s small? It’s doubled in the last four years.)

As an attorney in the field of intellectual property law, often referred to as IP, Koh had experience handling major cases and developed a reputation as a tough litigator. The appointment of Koh to the seat vacated by U.S. District Judge Ronald M. Whyte after he assumed senior judge status in March 2009 is all the more noteworthy due to her IP background.

“That is a very rare occurrence. I’ve been practicing in the Northern District for some time, and we haven’t seen very many appointees with her IP experience,” said Bijal V. Vakil, a former colleague. “I think everyone knows she’s a legal superstar.”

Over the course of the trial, Koh, a mother of two, would often stay late in her chambers following the day’s recess, according to Whyte, a George H.W. Bush appointee who still handles cases part-time. “She was very determined to do it right,” he said. “When you’re involved in a case like that—and very few and far between are that big—you get motions filed at your right and left, and there’s a team of lawyersworking on each side. She’s got to make decisions on an incredibly large number of issues that are very significant.

“I think she did an excellent job.”

Koh has declined interviews since becoming a federal judge, but it’s clear that her path to the federal bench involved an impressive blend of both the public and private spheres. After graduating from law school, she did policy work on civil rights issues for the Senate Judiciary Committee and was special assistant to the U.S. deputy attorney general at the Justice Department in Washington, D.C. She then hopped coasts to Los Angeles, where she investigated major fraud cases as a federal prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

She later transitioned to the private sector, rising to partner handling largescale patent law cases in the Silicon Valley office of McDermott, Will & Emery, where she impressed colleagues like Vakil with her “eagerness to roll up her sleeves and dig into any legal issue.”

“She will look under every stone in her research to arrive at the appropriate answer,” said Vakil, now an IP partner at White & Case in Palo Alto. At McDermott, Koh helped litigate a major case in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit changed the law around willful patent infringement, essentially eliminating the option of enhanced damages for plaintiffs.

Prior to her federal appointment, Koh served as a state trial judge on the California Superior Court for the County of Santa Clara, appointed in January 2008 by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. She juggled both civil and criminal cases on her docket and, notably, was reversed just once by an appeals court during her two-year service.

Her marriage to Stanford Law professor Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar, who serves as co-director of the Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, signals the couple is quite the formidable pair in the legal world.

“They’re both so impressive on paper, but when you meet them, they’re even more impressive in real life because they have such vibrant personalities and really care about people,” said Elaine Lu, Koh’s former Harvard Law classmate and a close friend.

The first in her family to be born in the United States, Lucy Haeran Koh is the daughter of first-generation Korean immigrants whose compelling personal history was included in the introduction to Koh’s Senate confirmation hearing and has surfaced in her own speeches.

Her mother, Eunsook Koh, escaped North Korea by walking for two weeks as a young girl to cross the border into South Korea. Her father, Jae Kon Koh, fought against Communist forces during the Korean War and later opposed Park Chung-hee’s military rule in South Korea. After arriving in the United States, he became a small business owner, operating a wig shop, a restaurant and a 7-Eleven.

Koh’s family settled in Maryland at first: her father attended Johns Hopkins University, while her mother received her Ph.D. in nutrition at the University of Maryland. The family later moved to Mississippi, where Lucy, the youngest of three children, attended a predominantly African American public elementary school during the years her mother taught at Alcorn State University, a historically black institution. Lucy would attend middle and high school in Norman, Okla.

Those in the judge’s circle say growing up in areas of the country not always known to embrace racial diversity had a deep influence on Koh and her career, propelling her to work at organizations like the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund during law school.

“She definitely wants to give everyone a chance to be heard, and I think that’s relevant to her background,” Vakil said.

Koh attended Harvard University as an undergraduate, returning home during breaks to help out in her father’s small businesses. By the time she entered Harvard Law School in the fall—

Barack Obama had just graduated that summer—the political climate over the issue of minority faculty hiring was already a key issue. Koh joined the Asian American Law Students Association and the Coalition for Civil Rights, an umbrella organization for law students from minority groups.

In November 1990, the coalition filed a lawsuit against the school, alleging discrimination against the hiring of women and minorities.

The students prepared legal briefs and delivered oral arguments themselves: Koh was one of the 11 named plaintiffs. Although the lawsuit was dismissed by the trial court, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court granted a direct appeal and heard arguments from the students. The students would press on, and on April 6, 1992, Koh joined eight other coalition members, in staging a peaceful 24-hour sit-in outside then-Harvard Law School Dean Robert C. Clark’s office in Griswold Hall. The students, who hence came to be known as the “Griswold 9,” faced threat of dismissal from the school without readmission, but were issued warnings instead.

But changes, however incremental, were on the horizon. In February 1993, the law school offered a tenured position to then-visiting law professor Elizabeth Warren, former special advisor for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in the Obama Administration. (She is currently on faculty leave as she pursues the U.S. Senate seat in Massachusetts.)

Prior to Warren’s tenure vote, only a handful of 60 tenured faculty at the law school were female—and none were women of color.

“The law school realizes statistically it is still in deep trouble concerning women,” Koh, by then a third-year law student, told the Harvard Crimson in a Feb. 6, 1993, article responding to the news of Warren’s hiring.

By the time Koh—who in law school was also involved in the Tenant Advocacy Project and Battered Women’s Advocacy Project—graduated in June 1993, the school had granted tenure to Charles J. Ogletree, making him the fourth tenured African American professor at the law school. It would be another five years until the first African American female professor was granted tenure—Lani Guinier, in 1998—and another decade after that for the first Asian American female—Jeannie Suk in 2010.

Koh, whose favorite class in law school was trial advocacy, was also not shy about expressing discontent with the school’s emphasis on corporate legal education over public interest and advocacy work. In a March 6, 1993 Crimson article, Koh said such focus contributes to “everyone in society looking at lawyers as parasites.”

“I am not surprised that Lucy Koh went on to become a judge,” said Philip Lee, Harvard Law School’s former assistant director of admissions, who wrote an article about the Griswold 9 for the Harvard Journal on Racial & Ethnic Justice, published last year. “Koh, like the rest of the student activists, was deeply engaged in public service while at Harvard Law School.”

In recent years, she’s returned to her alma mater to deliver speeches, most recently as 2008 during an event about women law school graduates, where she spoke about combating stereotypes against Asian Americans in the legal field.

Koh’s interest in diversity on the judicial bench hasn’t gone unnoticed. During her Feb. 11, 2010, Senate confirmation hearing, she was questioned by Republican Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama about those views. Federal judicial appointments have become a political flashpoint in recent years, due in part to the high number of stalled Senate confirmations. Obama, it is worth mentioning, has nominated minority judicial candidates at a rate that far surpasses his predecessors.

Diversity, Koh told the Senate committee, an assembled cast of family and relatives seated near her, “helps instill confidence in the justice system. “I believe it also reaffirms that this is the land of opportunity; anyone can grow up and become a judge,” she said.

In June 2010, the Senate unanimously confirmed her by a 90-0 vote.

For Koh, work on her highest-profile case yet is far from over. Samsung is seeking a new trial, while Apple wants the jury damages increased by another $707 million. Koh is to hear these matters in December. Which means, the Internet—and her now-rapt audience of court followers—haven’t heard the last of Judge Koh.

This article was published in the October 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the October issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only.)