Just how far has the fastest-growing minority group come politically? This story goes local, taking a closer look at three noteworthy case studies, to help answer that question.

by EUGENE YI

SO THIS IS THE YEAR. Finally, Asian Americans will matter. That’s what a casual observer might glean from the spate of articles heralding the arrival of Asian America onto the national political stage. A sampling of headlines:

“Could 2012 Be the Year of the Asian Voter?”

“Will Asian voters swing the election?”

“With surging numbers, Asian-Americans look for congressional gains”

“Asian-Americans take higher profile in congressional races”

“Overlooked Asian-American voters could tip scales in November election”

Based on heavy use of interrogatives and the conditional tense, there isn’t a lot of certainty about what to expect. Every election cycle includes reams of stories about uncourted demographics. But what’s really changed? For starters, this year, a record 17 Asian Americans are running for congressional seats. And, the Asian American population in certain swing states has finally grown large enough to be part of political parties’ attention.

All of this in the year of the Pew Research Center’s “The Rise of Asian Americans,” a much-talked-about study that touted Asian Americans as the “highest-income, best-educated and fastest-growing racial group in the United States.” Faster than you could say “model minority,” many prominent Asian Americans cried foul, justly citing income-, education- and health-related statistics for certain subgroups of Asian Americans that rank among the worst in the country.

There are, of course, few designations as loose-fitting as “Asian American,” a group of people who share nothing but ancestry from the world’s largest continent. Being Pakistani in Queens is very different from being Hmong in Milwaukee, or Korean in Cerritos. Or Korean in Kansas City, or Duluth, or Juneau, for that matter. As evidenced by the reaction to the Pew study, conclusions about a notional Asian America remain notoriously difficult to make.

Last year, a group of scholars published the results of the National Asian American Survey, the largest of its kind, which studied in 2008 the political engagement of 5,000 Asian Americans of Chinese, Indian, Vietnamese, Korean, Filipino and Japanese descent. Some trends were apparent. Asian Americans have grown significantly more Democratic over time. Yet rates of political engagement, given socioeconomic class and educational attainment, are lower than expected. Part of this was because the majority of Asian Americans are foreign-born, but mitigating factors vary by ethnic group. Ultimately, the picture that emerged was less a portrait than a tapestry.

James Lai studies Asian American political engagement, and is a professor of political science at Santa Clara University. “To me, if you’re going to talk about Asian American political participation, you need to know where the communities are first, and then you need to go into these communities to really understand each community,” he said. “Because they’re all different. The demographics are different.”

So with the election at hand, instead of speaking broadly about Asian America, on conditional terms, this story provides three case studies, in three different regions, that give a more nuanced picture of what is actually happening on the ground to grow Asian American political clout.

CASE STUDY 1: BUILDING THE PIPELINE

Anyone who flies into San Jose walks the terminals of Norman Y. Mineta San Jose International Airport, named after the former U.S. Transportation Secretary who began his political career in the region. Not bad for a demonstration of local Asian American clout. San Jose is in Santa Clara County, part of the San Francisco Bay Area, a traditional gateway city for Asian Americans. The county is notable, though, both for its inheritance of decades of Asian American political engagement, and for its embodiment of trends that point toward “the potential of Asian American political power,” according to Lai.

Traditionally, ethnic enclaves form in urban areas, but for Asian Americans, enclaves are increasingly forming in small suburban towns like Cupertino, home of Apple, Inc., and part of a cluster of heavily Asian American municipalities in Santa Clara County. According to Lai, Asian Americans, rich and poor, tend to settle in the suburbs, where about three-quarters of the Asian American population growth since 2000 has occurred. “These are not your traditional gateways,” said Lai. “To me that’s what is Asian America. The L.A.s, the San Franciscos, the New York City’s are the tip of the iceberg, and they’re still very important, but if we’re going to really understand where Asian America is today, we’ve got to look beyond that.”

Asian Americans have long been drawn to Santa Clara for the jobs in Silicon Valley and for the quality of the schools. Today, about a third of the county’s roughly 1.8 million residents are of Asian descent. Asian American politicians are so common that they sometimes run against each other. Scores have served as mayors, city councilmembers and school board members. Japanese American Mike Honda represents the district in the House of Representatives.

Santa Clara also stands apart because of the scale of its history of Asian American political activism. Many Japanese Americans resettled in the area following the internments during World War II, helping make it diverse enough so traditional racial politics held less of a grip on the area. Still, in 1970, Asian Americans made up only about 3 percent of the population of the county. Despite the lack of numbers, in 1971, Japanese American Norman Mineta became San Jose’s mayor, the first Asian American mayor of a major city. One of his appointees to the city’s planning commission was Honda, then a graduate student and activist.

“I was appointed to the planning commission not as an Asian, but as a person that was promoted by the Latino community to Norm Mineta,” Honda said, chuckling at the memory. “They had lobbied [Mineta] saying, ‘Honda’s the closest thing we’ve got to a Latino candidate in the community.’”

The Asian American population in Santa Clara County exploded in the subsequent decades, and the schools proved to be an entryway for many Asian Americans into politics, according to Honda, whose first elected position was on the San Jose Unified School Board.

“One of the comments I heard was that there was some angst about all these Asians winning all these academic schol- arships and prizes and recognition, and the parents weren’t involved in our schools,” Honda said. “So that was a clear message that y’all got to be involved in schools.” Heeding the message, many Asian Americans during the ’80s served on school boards, growing the local pool of political talent.

“[In Cupertino], pretty soon you had a majority of Asians on school boards,” he said. “And then pretty soon you had a mayor of the city of Cupertino who was Chinese American, and he was very successful and popular. And pretty soon you had city council people. Cupertino, Sunnyvale, Mountain View and then San Jose. More and more people started saying, ‘We can do this.’”

A pipeline formed to mentor Asian American political talent. Neophyte politicians needed help in everything from fundraising to voter mobilization to Robert’s Rules of Order. Honda said he was careful to urge Asian Americans not to align purely by racial concerns, especially as Asian Americans started running against other Asian Americans. “I started saying, ‘You don’t endorse Asians just because they’re Asians.’ We’ll have good candidates and bad candidates,” he said. “These are choices you make, and this is about a mature community. And because we don’t support one over the other, it doesn’t mean we hate the person. It just means we have choices.”

Attorney Otto Lee, a first-generation Chinese American, held a series of offices in Santa Clara before deciding to run to represent the neighboring 22nd Congressional District this year. He spoke of both Mineta and Honda as mentors. “We’re very close, and having them be the trailblazers certainly makes this journey a lot more understandable,” he said.

The tipping point for Asian Americans in Santa Clara came during the 1990s, according to Paul Fong, a California assemblymember dubbed a “godfather” of the Silicon Valley Asian American political machine. Until that point, Fong said political mentorship occurred as an ancillary mission for Asian American organizations focused primarily on social services. But when the Asian American population reached about 25 percent, Fong helped found a series of organizations focused on political missions, including the Asian Pacific American Leadership Institute, which places students in internships with civic offices, and the Silicon Valley Asian Pacific American Democratic Club, which provides networking opportunities.

Proximity to cash-rich Silicon Valley has made Santa Clara a frequent campaign stop for many elected officials. Going back decades, Asian Americans have been prominent political donors, but the rising number of candidates reflects a generational shift, according to Lai. Immigrants, who are shut out from the political process in other ways, often get engaged financially, he said. “While the older generation is leading the charge in terms of political contributions, we’re seeing the emergence of a professional, late 20s, 30s, 40s crowd that is now saying, ‘We are ready to lead, and we want to lead and work together.’ It’s part of the political maturation of any community,” said Lai. “We’re finally seeing it start to take shape.”

The immigrant population of the county has jumped 37 percent since 2006, and incorporating more recent immigrants has proven to be a challenge, according to Fong, who speaks of his work as helping an “API movement” inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Everyone that jumps into my pipeline will have to understand that the movement originated from somewhere. And that’s the lesson that I give them. That’s the only lesson I give them. But a lot of people don’t buy into it. A lot of recent immigrants don’t buy into it.” The National Asian American Survey found that experiences with discrimination are likely to spur greater involvement in politics. But with Asian Americans being a fixture in the economic and political power structure in Santa Clara County, such experiences are likely harder to come by.

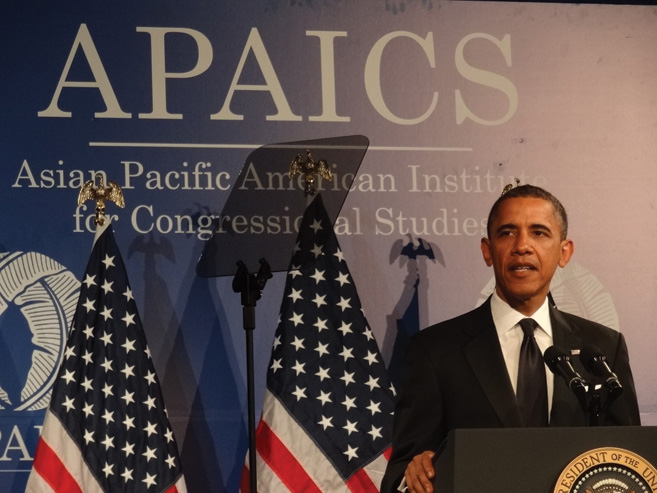

It’s a fact of life for Asian Americans in places like Santa Clara County. The population boom, the politicians, first- and fourth-generation Asian Americans, all rubbing shoulders. It’s sort of neat, the kind of thing that isn’t happening anywhere else, and ultimately, probably won’t. “How leaders are developed is so organic, and the way that institutions form are so specific to the locale,” said Gloria Chan, president and CEO of the Asian Pacific American Institute of Congressional Studies, a non-partisan group that tracks APA congressional races. As much as an organization like hers would like to bottle what Santa Clara has built up in the way of an Asian American political pipeline and replicate it elsewhere, regional variations make that difficult to do.

Asian American politicians may seem omnipresent in Santa Clara, but Fong said there is still a ways to go before achieving parity. Only 15 percent of elected officials are of Asian descent in a county that is 32 percent Asian American. The numbers are not far off from the national figures. There are only 10 Asian American congressmembers, about 2 percent, for a demographic that makes up 5.6 percent of the total population. Even states like New York have never had an Asian American representative. It may be the dawn of a new day for Asian Americans in politics, but even in Santa Clara County, there’s a long way to go.

CASE STUDY 2: THE ASIAN AMERICAN CANDIDATE

The 23rd District of New York spans the bulging top of the state, from Canada to Vermont, with tracts issuing downward like rivulets of maple syrup. It is mostly rural, peopled by the descendants of European settlers. It would seem to be a strange place for an Asian American to run for Congress. But Nate Shinagawa, 28, is running for the 23rd District in New York.

Shinagawa, whose mother is an immigrant from Korea, em- bodies something of both the old and the new in Asian America. Like many Asian American candidates, he is running in an area without a large Asian population. But he is young enough to have benefited from local Asian American civic organizations, and he in some ways embodies exactly how ready the community is to support its candidates.

Shinagawa grew up in Berkeley, Calif., and his family history recalls many of the bullet points of 20th-century American history. During World War II, the government interned his Japanese American grandfather, who responded by enlisting in the Armed Forces. Shinagawa’s father, an ethnic studies professor, fought a protracted battle against police in Sonoma County, Calif., over the controversial shooting death of a Chinese American graduate student.

As for Shinagawa himself, his political education started early, with internships in congressional offices through APAICS and the civic-minded nonprofit Korean American Coalition. He attended Cornell, in Ithaca, N.Y., where he helped a group of local pizza workers fight for unpaid back wages. He decided to stay in the area after graduating, and became a county legislator at age 22.

But being away from the major urban areas meant that Shinagawa made a name for himself without the benefit of a network of Asian American support, either from voters or fellow politicians. It speaks to his political gifts, and his ability to reach out to people who might not be used to the idea of having an Asian American represent their concerns.

“Storytelling is so important. I see a lot of Asian American candidates get up on stage and talk about their accomplishments. Their education. And what they want to do. And that’s fine,” he said. “But we’ve got to tell stories about our family background. Because people find the Asian American story, fighting to become part of the American dream, a quintessentially American story. And it helps us connect with voters.”

Now, he faces a tough race in a district that leans Republican. His opponent, medical debt collector and freshman Tea Party Republican Tom Reed, had a war chest of more than $1.4 million as of June 30, of which PAC contributions make up 54 percent, according to the website Opensecrets.org. Reed is a proponent of the controversial practice of fracking, and PACs representing the gas industry have donated to his campaign. Shinagawa, who opposes fracking, had amassed only about $320,000, individual donors making up 87 percent of his total.

Despite the fundraising disadvantage, Shinagawa sounds upbeat. Relentlessly so, radiating a can-do-it-ism that is palpa- ble over the phone. Redistricting has helped him a bit, with the district now including the college town of Ithaca. Shinagawa’s candidacy has been strong enough to garner the attention of national political networks. Like the vast majority of this year’s crop of Asian American candidates, Shinagawa is a Democrat, and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee listed his run as an “emerging race,” a designation acknowledging it as potentially competitive. National Asian American leaders have provided him with support. “I’ve received tons of help from Congresswoman [Judy] Chu, Congressman [Mike] Honda. They have been amazing leaders,” he said. He also recently got the endorsement of Sen. Daniel Inouye, president pro tempore of the Senate and the third in line for the presidency. Inouye’s support surprised Chan of APAICS.

“I was super impressed that he was able to get Sen. Inouye’s endorsement. He never endorses anyone unless they’re going to win,” said Chan. It’s an interesting conundrum. Shinagawa, like many of the other Asian American congressional candidates, has the full force of the incipient Asian American national political network behind him for the first time in his career, as well as the interest of the Democratic establishment. Still, he’s an underdog, and probably won’t match his opponent’s fundraising totals. In a year when Democrats are fighting an uphill battle on the fundraising front, this is perhaps not surprising. But in some ways, it boils back down to Shinagawa, a compelling Asian American candidate, running in a nearly all-white district, just as he was at the beginning of his career, with only his prodigious political talent to fall back on. In some ways, little has changed for an Asian American candidate. No matter the support, it usually falls on the strength of the candidate.

CASE STUDY 3: COURTING THE ASIAN AMERICAN VOTE

Asian American voters in Virginia would seem to be a fickle lot. In 2008, they went for Barack Obama over John McCain, 66 percent to 33 percent, according to exit polling by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund. But in 2009’s gubernatorial election, Republican candidate Bob McDonnell won 58.5 percent of the Asian American vote, according to polling by the League of New Voters. Granted, 2010 was a bad year to be a Democrat running for the grocery store, let alone for political office. But in a battleground state like Virginia, a few tens of thousands of votes can swing the state.

The Asian Virginian population has leapt 71 percent in the past 10 years, to more than 400,000 total, according to census figures. The vast majority live in the suburbs of Northern Virginia. Fairfax County is about 18 percent Asian American. Neighboring Loudoun County is at about 15 percent. These areas are illustrative of the growth of the Asian American population in the South. Virginia provides a hint at the greater role Asian Americans will play in upcoming elections. An APIAVote/Lake Research Partners poll earlier this year found that about half are likely Obama voters, hewing closely to the broad trend that Asian Americans tend to be Democrats. But the poll also found about a quarter to be undecided.

–Asian Americans who voted in Virginia in 2004: 29%

–Asian Americans who voted in Virginia in 2008: 61%

Source: Census

Mark Keam, 46, a member of Virginia’ s House of Delegates, has 16 years of experience helping the Democratic Party shape its election outreach. Asian American voters first demonstrated their clout in 2006, he said, when a clip of then-Sen. George Allen went viral after he called S.R. Sidarth, an Asian Indian American volunteering for his opponent, by the obscure slur “macaca.” Allen lost the election by less than 9,000 votes, and he lost Asian Americans by about 8,000. Seeing an advantage, the Democratic Party has since made a concerted effort to tar- get the Asian American vote, Keam said, and it has expanded every year.

“On the Democratic side, at the presidential level, as well as at the state, county, Senate and House levels, we have seen a much more aggressive, more robust, wider and deeper bench of efforts to reach out than I’ve ever seen,” he said. “Just from a purely Asian American perspective, we’re going to run their clocks on this end. If the election was just among Asian voters, I would say Obama wins two to one.”

Peter Su, 41, thinks otherwise. He currently serves as the agency director of the Virginia Department of Business Assistance, and he helped craft the Asian American strategy that helped McDonnell win the governorship in 2009.

“[The other side], they just assume Asians are Democrats,” he said. “We’re simply hitting the replay button on McDonnell. If we can replay what we did with McDonnell, I’m sure Romney will get a good percentage of Asian votes and a good percent- age of Asian support,” said Su, who’s aiming for 55 percent.

Recent Asian American enclaves, like the ones in Northern Virginia, are now getting more attention from national campaigns than the traditional city centers.

“I think it’s indicative of a shift that is happening,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, a political scientist at the University of California, Riverside, who co-authored the National Asian American Survey. “I think, for a while, Asian Americans were ignored by those parties. And then I think they were selectively mobilized by Democrats. Now I think they’re selectively mobilized by Democrats and Republicans.”

So now, at least in Northern Virginia, both sides offer extensive in-language outreach, high-profile surrogates and a platoon of Asian American staffers and field deputies. The arguments on both sides strongly reflect party orthodoxy. Keam spoke of the recovery-in-progress and the benefits of Obama’s health care reform, and Su emphasized the still-weak economy and lower taxes (“Koreans hate taxes. They do their stores cash- only so they don’t have to pay them,” he joked).

Percentage of U.S. Population of Asian descent: 6%

Percentage of Congress members of Asian descent: 2%

Number of Asian American members of Congress in 2008: 6

Number of Asian American members of Congress in 2012: 10

Number of Asian American congressional candidates in 2008: 8

Number of Asian American congressional candidates in 2010: 10

Number of Asian American congressional candidates in 2012: 30

Asian American congressional candidates in 2012 who advanced past primaries: 17

Number who were democrats: 15

Asian Americans who voted in 2004: 42%

Asian Americans who voted in 2008: 47.6%

Asian American who say they will vote this year: 83%

Su thought Asian Americans would be too educated to be affected by the stricter voter ID laws recently passed in Virginia, while Keam spoke of keeping lawyers on hand for any voter ID-related concerns. Su summarized his pitch thusly, “My perception, if I were to be as objective as I can, is that [Democrats] tell the Asians that ‘the Democrat party’s the one to take care of us, we’re disadvantaged’ … but [Asian Americans] are some of the highest achievers.”

Echoes arise of the conversations surrounding the Pew Research Center’s recent study, with some decrying its affirmation of model minority stereotypes, while others emphasized the gains Asian Americans have made. These are old questions within the Asian American community, of course. What’s no- table is how they’re hewing so closely to national conversations about the role of government in public life. How this question gets answered going forward may drive Asian Americans to one party or the other.

For now, though, it’s hard enough just to assess which way Asian Americans have gone, let alone which way they will go. The swing from 2008 to 2009 has been widely reported upon by various news outlets, but a closer look again shows the perils of generalizations regarding Asian Americans. The League of New Voters poll only surveyed Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese Americans, excluding the quarter of Asian Americans in Virginia of South Asian descent. Given that Vietnamese Americans tend to be reliably Republican, and South Asian Americans tend to vote Democratic, the effect of the swing may have been overstated.

Flawed as the numbers may be, both parties are paying attention. For his part, Keam welcomed the competition for Asian American votes. “As a Democrat, I’m not happy. But as an Asian American, I’m happy to see Republicans doing out- reach the right way.”

Still, extra outreach to Asian Americans in swing states like Virginia, Nevada, North Carolina and Florida ignores the vast majority of Asian Americans. This brings the demographic in line with the vast majority of Americans who don’t live in swing states, initiating Asian Americans into the peculiarities of the electoral college. This, perhaps, is progress.

SO THE QUESTION isn’t so much whether Asian Americans will matter this year, but where. In booming Asian American areas like Santa Clara County, Asian Americans will continue to entrench themselves in the political firmament. Elsewhere, even if candidates like Shinagawa are unsuccessful in their bids, the mere act of running a stirring campaign will stretch standard notions of what kind of person can represent whom. And in swing states and in the South, Asian Americans will be courted to help win a state (and potentially the presidency) by one or two points.

A national identity for Asian Americans, though, remains as elusive as ever.

The LGBT and Jewish communities have both leveraged signature issues, along with donations, to become sought-after demographics. But there is no unifying issue as distinct as same- sex marriage or Israel’s sovereignty for Asian Americans. The 2010 AALDEF study found that Asian American voters’ top three concerns were the economy, health care and civil/immigrants rights—issues not unique to the Asian American community. A more granular look, as always, reveals differences among ethnic groups. Korean Americans ranked civil rights/immigrant rights highest, Chinese Americans gravitated toward health care, and Vietnamese Americans emphasized education.

The results point toward the core question of Asian America: does it even exist? In the National Asian American Survey, only one-third of Asian Americans said they had shared political interests with other Asian Americans. Specific issues define specific subgroups. It’s the tapestry again.

But younger Asian Americans feel a sense of solidarity with their fellows—linked fate, as it is known in academic circles—according to Lai, the professor.

“It could be a Korean giving [a donation] to a Chinese American candidate,” he said. “They see themselves maybe as Korean American first, but also as an Asian American. They can see this sense of linked fate … that what affects another Asian ethnic group can affect me as an Asian as well. And I think we’re starting to see that taking greater shape among the younger generation, regardless of ethnicity.” He cited political organizations like the ones in Santa Clara as fostering pan- Asian solidarity. Such organizations are growing in thriving Asian American communities nationwide, from Washington state to Washington, D.C., and groups like APAICS are trying to spread best practices among them. These groups may, some- day, form a political machine around which to organize, if and when parity (or some more urgent issue) comes to the fore.

The National Asian American Survey pointed toward two trends in Asian America: assimilation and racialization, meaning the increased awareness of racial identity. Though assimilation reduces identification with an ethnic group, and racialization increases it, both have the same outcome: increased political participation. In a sense, these are the two most important trends playing out now. Successful Asian Indian American politicians like Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal and South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley are two examples of how assimilation can help propel candidates of color in unexpected locales.

Meanwhile, in enclaves like Santa Clara County, there remains a sense of an ethnic mission. These are the competing strands of ethnic identity in America, period. And the story they weave for Asian America seems to be one of growth, with its starts and stops and uncertainties. It leaves us able to countenance no conclusion stronger than what Ramakrishnan, the co-author of the national survey, told me: “I think the progress is uneven, but it is moving forward.”

This article was published in the October 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the October issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only.)