In “Blinded by the Light,” Viveik Kalra plays Javed, a shy, slouching student with a thick mop of black hair and an obsession with Bruce Springsteen. But at the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival this past May, Kalra was confident and cheerful, and had slicked all that hair out of his eyes—his love for the Boss is real, though. Ditto for Sarfraz Manzoor, the writer and Springsteen superfan behind “Greetings From Bury Park: A Memoir,” on which the film is based. There was a restless, excitable energy between the two that likely came from the high of that night’s successful premiere.

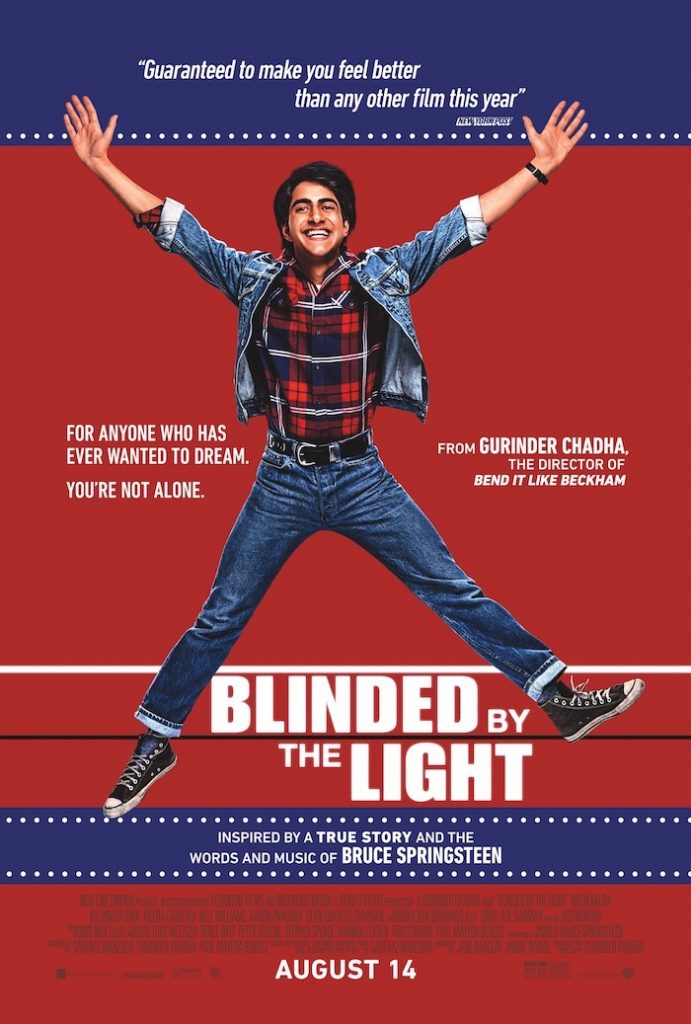

The film follows Javed as he struggles to embrace his voice as a writer and break free from his parents’ traditional expectations. And through Bruce Springsteen’s rock ‘n’ roll attitude and music, he does just that. “Blinded By The Light” hits theaters on August 16.

Character: How does it feel to be at the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival?

Viveik Kalra: It’s cool, man.

Sarfraz Manzoor: Is that where we are?

Kalra: Ugh, Sarf, stop it, they’re going to think you actually mean that. It’s amazing, it’s lovely, we’re in this sort of wonderful, cultural hub. It’s a pleasure to be here, doing this groundwork, and seeing how audiences respond to it. It’s lovely and it’s eye-opening to see how different people respond to all the different bits.

Manzoor: It’s just incredible to have people who are not from Luton, watching this film. That’s an amazing thing. But the second thing is, it’s really interesting when you get people from different communities coming to see it. One of the things I’ve noticed in terms of what people tweet and stuff is they say, “Oh, I grew up in a Greek family, but I’m seeing connections.” And I love that, because it shows that what we think of as unique, individual kind of barriers and cultural things… actually, a lot of different people have them. And it’s when you go to festivals like this and you have different kinds of audiences seeing it, having those kind of connections and parallels.

That is a really interesting barrier to break. Depending on the different cultures, it can seem really different.

Manzoor: Yeah. But they’re actually quite common. Last time we were in L.A., this girl came to me and she said, “I grew up in a small, Baptist town in Texas. I want to be a singer-songwriter, and you’ve told my story.” I really didn’t realize that I had done that, you know?

That’s really cool! So, can you give me a brief description of the film in your own words?

Manzoor: It’s about a kid who’s growing up in 1987, 16 years old, coming from a working class British Pakistani family, with parents who have expectations that are fairly traditional. This kid writes poems, he likes to be a writer, but it just seems like an impossible dream. Then, a mate of his introduces him to the music of Bruce Springsteen, and suddenly, Springsteen gives him the ammunition to think that maybe what seemed impossible is possible and he can be a writer. But in doing that, he has to stand up to his dad, but he doesn’t want to burn his bridges, either. It’s really about, “Can you make your dreams come true while still keeping your parents onboard? Without losing them?”

What do you think was the biggest challenge in making this film? Either artistically, or just logistically…

Manzoor: What were your challenges?

Kalra: There weren’t any for me. As an actor you’re privileged, generally, unless you produce or whatever as well. You can come into a process once stuff is sort of semi-polished. So once the scripts have been done, this has been done. But in the production, with the writing and all of that stuff, it takes a long while beforehand. So, I come at this point where it’s sort of semi-finished.

Manzoor: Good enough for you, basically.

Kalra: Yeah, it needs to be good enough for me to do it, and then I do the acting. So, I had to make sure, even when we were at Sundance, I was like, “I have to make sure I let you and [director] Gurinder speak for me at least 75 percent of the time,” because you’ve spent that much more time with the project than me.

Manzoor: I think the big challenge was—this was something both me and Gurinder had—was how to tell a story that felt honest, that had nuances, and not make it formulaic. The things that are interesting about films are the things that are weird and different, but I think there’s always a pressure to iron them out and to make something you think more people will like. I was always trying to hold onto as much factual or emotional truth, and not make it too simplistic. I wanted to try and have as much complexity as you can.

Kalra: That’s real life. People are nuanced, no one person is one thing, and so portraying that in a sense is important.

Manzoor: Yeah. When you’re trying to make a film, how do you do it so it can retain all the things that make it odd and true?

This one’s more specifically for Kalra, but how did it feel for you to immerse yourself in such a different time period from the one we live in? How did it feel going back to the 80s?

Kalra: It was weird I guess, but not that hard. If it wasn’t for that collaborative effort, I would just be standing with no props around me, with no set around me, in my own clothes. So, in terms of what I have to imagine, I don’t have to imagine much, because everything’s already around me, everything’s created around me.

Manzoor: But you had to get used to Walkmans and cassette machines and things like that. Because that wasn’t…

Kalra: Don’t bring that up. That was… ugh, yeah.

That was a struggle?

Kalra: The Walkman just—I had issues with that Walkman throughout. And record players, I mean I had to find out how to put a record on a record player, and people were apparently cringing, because that was like an original Bruce record.

Manzoor: Obviously I grew up with vinyl records and Walkmans and stuff, but in the era of streaming and Spotify, that’s all quite weird equipment, isn’t it?

So can you tell me a little bit about the link in the film between music and activism?

Manzoor: Is there one?

There seems to be!

Kalra: It’s the sort of thing where, if you’re 16, working class, you’re living in a town just outside London in 1987, you can’t not talk about race. So, that was just a part of the puzzle, a part of the picture, that it’s necessary that it’s said.

Manzoor: The thing about the Bruce stuff was that we wanted the music to be a character in the film, and the songs to be characters in the film. The reason you see those words come up, is because they are absolutely relevant and important. For example, where Javed first puts on “Dancing in the Dark,” I love that scene. Gurinder did it brilliantly, because it reminds me of what it’s like to listen to a great song for the very first time, it just has that absolute power to it. There are reasons why those songs are played at those points. It’s absolutely meshed and embedded in the film.

Who is your favorite Asian character?

Kalra: Asian character, oh, sh-t. That’s a good question.

Manzoor: Favorite Asian character…

Kalra: Who’s your favorite Asian character? Oh, crap. Dumbfounded, even the journalist [Manzoor] is dumbfounded.

Manzoor: I’ll tell you, I know who it is, I know who it is.

Kalra: Who’s yours? I’ll think of mine.

Manzoor: Have you seen “Lion?” The 5-year-old boy—

Kalra: Spectacular.

Manzoor: The 5-year-old boy in “Lion” is genius.

Kalra: And I can’t think of anyone, but I’ll say it’s great that there are more now. It’s great that we’re experiencing an influx of Asian characters, because we’ve been deprived of it for so bloody long.

Manzoor: Oh, I’ll tell you the other thing. And I haven’t seen it yet, but I’m going to say, Riz Ahmed playing Hamlet. Just the fact that he’s doing it.

Kalra: Yep, that’s amazing. Riz is playing Hamlet, Dev is playing David Copperfield. Amazing, how does that happen? Times are changing.