Editor Notes: This article has been updated for Character Media’s upcoming annual issue.

SAG-AFTRA members are currently on strike and cannot promote their film and TV projects. The reporting for this article was conducted before the strike began.

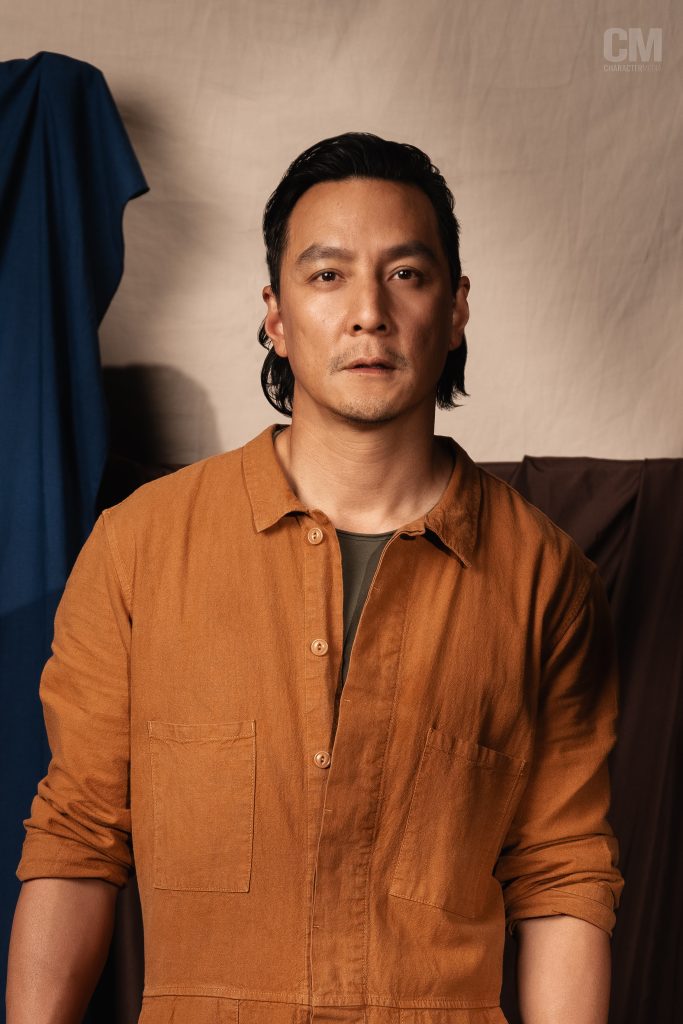

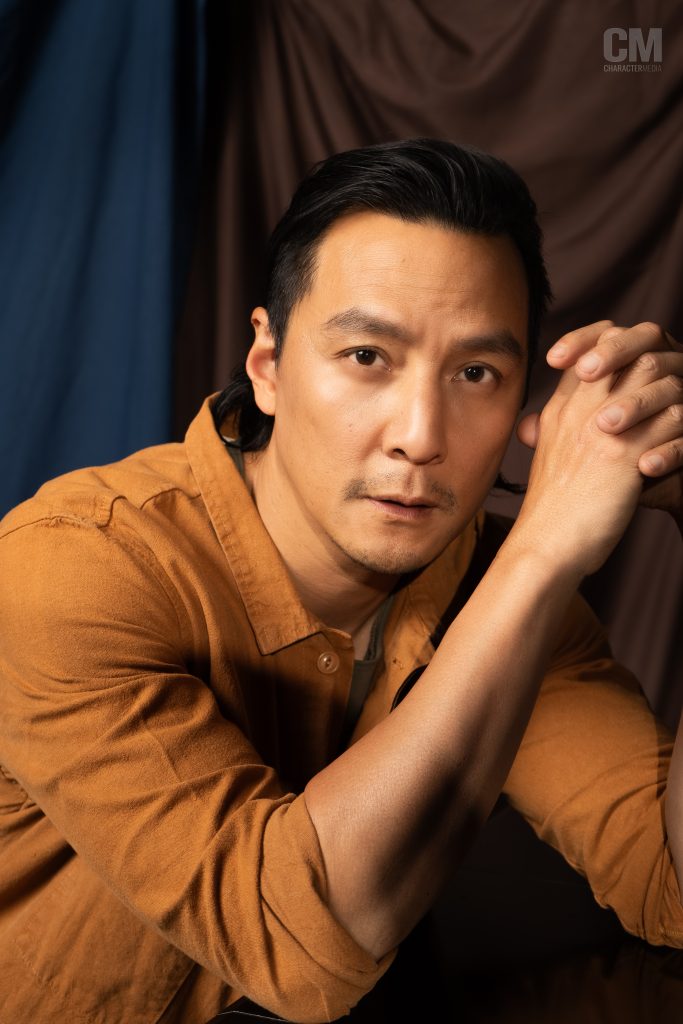

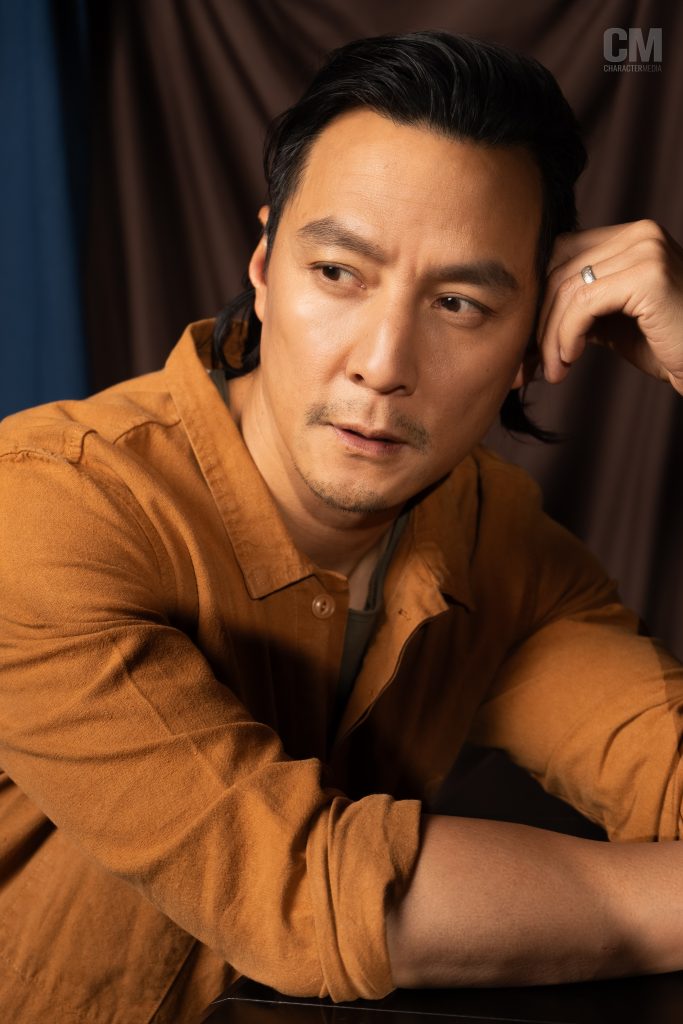

One of the best pieces of advice Daniel Wu has ever received since starting his 20-odd-year career was: “If you can not do action, don’t do action.”

Wise words from action legend Jackie Chan, who, as Wu’s mentor and manager at the time, wanted to ensure that the younger actor did not fall into the industry typecast as he did. Wu took this advice to heart, and, for a long time, didn’t tell anyone he practiced martial arts out of fear that he, too, would be stuck playing the same roles over and over again. If you check his filmography, it’s stacked with arthouse films like “Bishonen,” thrillers like “Devil Face, Angel Heart,” and comedies like “The Heavenly Kings.” But of course, that doesn’t mean he hasn’t utilized his martial arts training.

Throughout his career, especially in his later projects in Hollywood, Wu has begun to infuse his martial artistry with his acting in AMC’s “Into The Badlands,” and most recently, “American Born Chinese,” where he plays Monkey King Sun Wukong from the beloved “Journey to the West” story. In the midst of promoting the Disney+ series, Wu sat down with Character Media to speak about the difference between the Hollywood and Hong Kong entertainment industries, how “American Born Chinese” affected his parenting style and more.

Character Media: How was it seeing yourself in the full Sun Wukong (Monkey King) costume?

Daniel Wu: It was pretty amazing. First of all, shout out to the special effects makeup team because even close up in the mirror, it looked really good. I’ve had various experiences with prosthetic makeup over the years and it’s really evolved to a point now where it looks so realistic. I was just staring at myself in the mirror making all kinds of different facial expressions because it’s really transformative. Almost every actor talks about wishing they could disappear into a role and this is one way you can certainly do that.

CM: What inspirations did you pull from for this role? Did you watch any monkey videos?

DW: I was looking at inspirations for the hair because we went through different versions of how the hair should be. We were looking at different types of monkeys because the Monkey King is actually not based on a chimpanzee. He’s more based on the Asian type of monkey — a smaller monkey, a golden-haired monkey. That’s kind of where the gold hair comes from [in] our look. Then, I looked at some of [the] behavior like little kicks and movement — but we decided to tone that down a little bit for this version of the Monkey King. So it’s not [a] caricature, but there are homages to the monkey’s movement.

CM: Your role as Sun Wukong in “American Born Chinese” was deeply connected to fatherhood. Has the part affected the way you parent your daughter as well as your thoughts about your own parents/upbringing?

DW: It’s interesting because I didn’t expect that, but it made me rethink how I was brought up. The way the Monkey King treats his son, Wei-Chen (played by Jimmy Liu), in some of the scenes mirrors the way my dad used to speak to me. And then, [when it comes to my parenting] instead of being a helicopter parent and trying to shield them from making mistakes, you have to go: “Okay, well look, she made a mistake on her homework here. Do I tell her to correct it or do I let her make that mistake and then realize she did it wrong?” I was dealing with that, especially during COVID and distance learning. I had to reel it back because I was being too overbearing and it was hurting our relationship. And it really reflected on what’s happening with these characters; when I read the script, I was like, “I totally get what’s happening here with this guy and his son.”

CM: I really enjoyed episode four where we got to see Sun Wukong in his rebellious era. What was your favorite part of playing that younger version of him?

DW: I really like that episode because it allows people to see what Sun was like before he became a father. The Monkey King I’m playing is very different from the “Journey to the West” Monkey King. He’s more mature, he’s a father, he’s got responsibilities. He’s no longer the young, wild, rambunctious kid that he was. But episode four shows who he used to be. That makes the kind of relationship between him and Chen even more poignant because his son is going off on this mission on his own. The Monkey King doesn’t like this, but is reminded by the Goddess of Mercy (played by Michelle Yeoh) that he was once that way. You have to give him the space to grow on his own.

CM: For most of your career, you’ve split your time between the Hong Kong and American movie industries; what was it like balancing the two? How has that changed in the 25 years since you started?

DW: These are two very different industries and the biggest difference in working in the Chinese film industry (Hong Kong, Mainland China and Taiwan), is that I’m Chinese, so race wasn’t an issue at all. There was never “going for that Chinese role,” or never “going for that one Asian role,” because every role is Asian. I didn’t have to think about that at all. It is so weird because when I first came back [to the States], I had not thought about it, so when I was doing “Into the Badlands,” all the Asian American media members would be like, “Wow, this is such a great moment.” And I was like, “What’s so good about it? I’m just doing the same thing I’ve been doing, being a leading man.” To me, that wasn’t anything special because I’ve been doing it for 20 years. But you have to look at a different lens for Americans — it’s rare to see an Asian American male leading a TV show. Then, slowly, I started to understand that it was a totally different way of thinking for Asian Americans. We haven’t had representation. And I had forgotten that because I was in a place where representation wasn’t an issue. Then coming back here and slowly realizing the importance of that, especially for the next generation for my daughter to be able to see Asians on screen — that’s why I’m doing the work.

CM: Since “American Born Chinese” had the younger generation of actors like Ben Wang and Jimmy Liu in the forefront, what was some advice you wanted them to reap during your time on the set?

DW: I always say to them, “Keep refining the craft.” [That] should be the most important thing to you. It’s very easy to be confused nowadays with social media and all that stuff, like you need to build your “celebrity” or that you need to build followers. That’s a side gig — that’s not the main gig, don’t concentrate on that because that’s not what you want to be doing at the end. You need to be a good actor before you have the opportunity to do other stuff. Keep refining your craft, keep honing it so that you’re ready for those big opportunities that come.

CM: For our last question, you’ve been vocal about anti-Asian racism, especially in the aftermath of COVID-19, how do you hope to use your platform to make a change toward the causes you support?

DW: My initial involvement in all of it was a raw emotional response. I don’t consider myself an activist. I look at myself as an advocate for issues that I care about. And this is certainly something I care about — because our women and elders were being attacked relentlessly and still are without any repercussion. I wanted to draw attention to that as much as possible. I do feel this kind of imposter syndrome, I was like “What am I doing here? This is not what I’d normally do.” But I educated myself on these issues, and connected with people who are really in touch with those issues like Asian Americans Advancing Justice and Stop Asian Hate, all those groups have been studying [these issues] for many years.

I think the most important thing was to try and get our community to stop just putting our heads down and to stand up for ourselves as Americans. Our immigrant parents have a completely different mentality than us — they came to this country leaving a probably more terrible situation so they’re just happy to be given the opportunities they have. So they weren’t privy to complain about certain things. But those of us who [were] born here are American, we deserve the same rights as every other American does. We should be treated the same — the constant otherizing puts us out of the American fabric. I realized that we need to work on establishing ourselves as being a part of America and highlighting the contributions we’ve made to this country.

This article appeared in Character Media’s Annual 2023 Issue.

Read our full e-magazine here.