New mothers and fathers know the agony of letting your baby cry for even a moment without rushing to comfort her. Now just imagine putting your newborn in a basket, pinning a $20 bill to her blanket and leaving her to howl for two days straight in the marketplace, while mosquitoes feast on her pudgy little face before she finally succumbs to thirst, starvation and exposure. And yet this is what happened—not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of times across China during its one-child policy that spanned from 1979 to 2015.

Baby abandonment is just one of the many horrors documented by Nanfu Wang (of “Hooligan Sparrow” fame) and Lynn Zhang (a.k.a. Jialing Zhang), the directors of “One Child Nation,” which weaves together Wang’s personal story of becoming a new mother and a larger examination of how government policy impacted her own community. With a baby strapped to her frontside and a camera on her shoulder, Wang travels back to China, where she interviews her family members in her rural home.

She is surprised to learn how the policy deeply impacted her relatives. Her uncle abandoned his baby in the aforementioned way. Her aunt gave her daughter to a child trafficker. She meets a midwife who prays for redemption for all the babies she had killed. Wang meets with village elders who all say the same thing like a mantra: “It had to be done” and “there was no choice.” Her mother laughs uncomfortably during the interview and says, “There would be cannibalism without it.”

China was a poor country, and its citizens had endured famine and starvation. By 1979, the world’s most populous country was hurtling toward the one billion souls mark. The government feared that this population boom would tax its resources and the country would descend into chaos. Hence the one-child policy. Wang and Zhang uncover how far the state went to enforce this law, thereby underscoring the idea that the Chinese place far more importance on the state than on the individual.

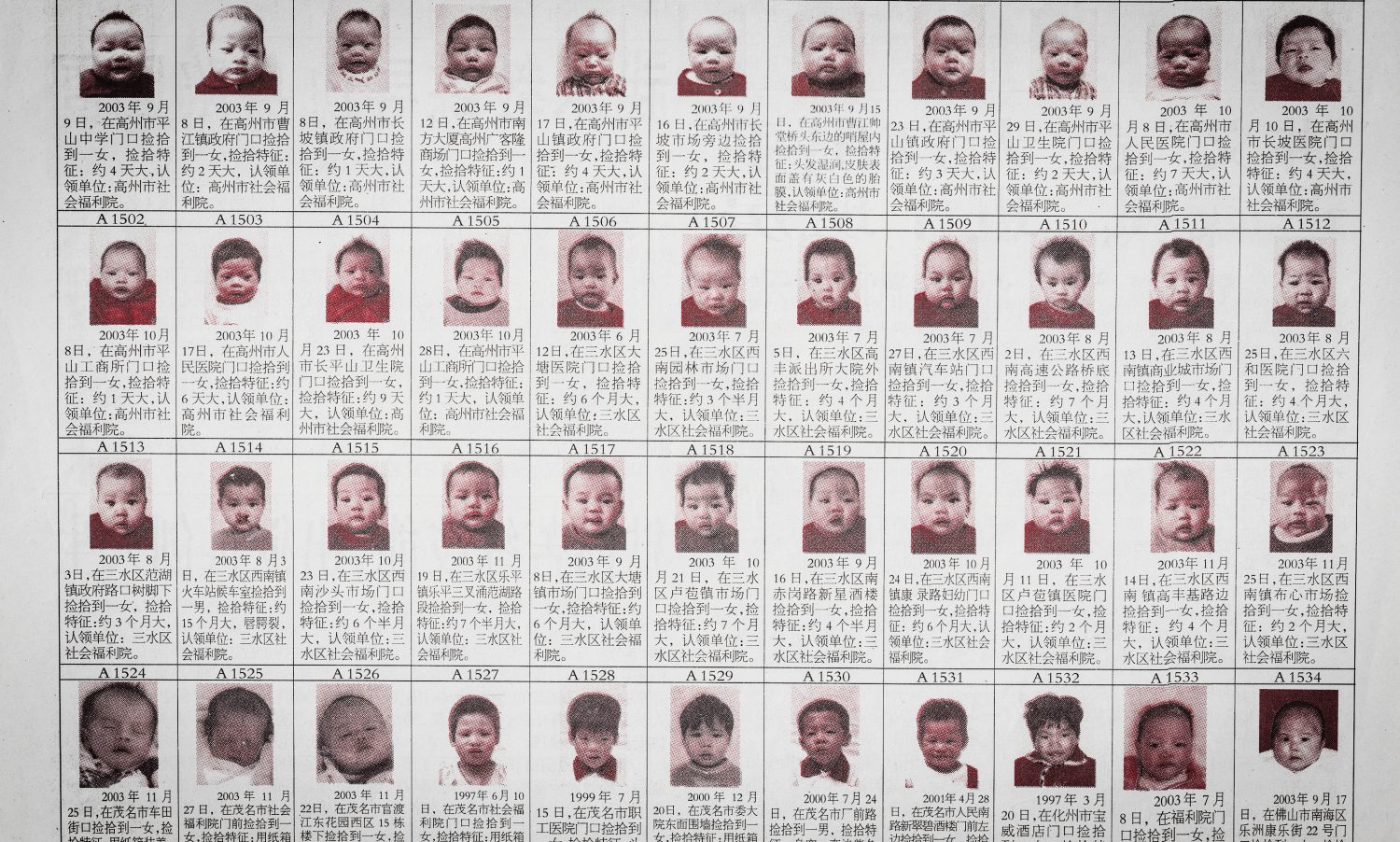

Beyond the small village community, they interview provincial nurses who induced late-term abortions and killed fetuses with their bare hands. They meet an artist who was arrested for taking photos of babies curled up in yellow plastic bags at landfills. They chat with a security guard who went to prison for “human trafficking”—because he and his family members couldn’t bear to let the female babies rot in the streets, they took them to orphanages. Due to changes in international adoption laws, millions of Chinese girls were adopted overseas, sometimes against the will of their families.

“One Child Nation’s” well constructed narrative moves deftly and grippingly from macro issues of state-induced family planning (to put it mildly) to the most intimate moments of heartache and disappointment. For example, a set of twins were separated because of the one-child policy. The older twin was sent to an American family, while the younger one stayed behind in China, yearning to wear matching outfits and coordinated hairstyles with her missing sister. But when they finally connected on social media, she hesitated to ask her any intimate questions, afraid that she would annoy her and get blocked.

It’s one thing to make an absorbing feature, but it’s another kind of feat to make a prize-winning documentary in a country that’s determined to arrest you for your storytelling and filmmaking. This is what Wang and Zhang have achieved.