Confession time: My folks aren’t great cooks. Growing up, they were working professionals who had little interest in kitchen tinkering. There was no trickle-down culinary wisdom waiting for me. I learned how to prepare Chinese food the other old-fashioned way: I read a cookbook.

These days, cookbooks are less like recipes clipped out of check-out aisle magazines and share more with prestige coffee-table tomes. They now represent histories and communities, lifestyles and life stories. As I soon realized, more and more are being penned by second-generation Asian Americans like me. They’re windows into an evolving Asian American food culture, a way to teach us about ourselves through the medium of food.

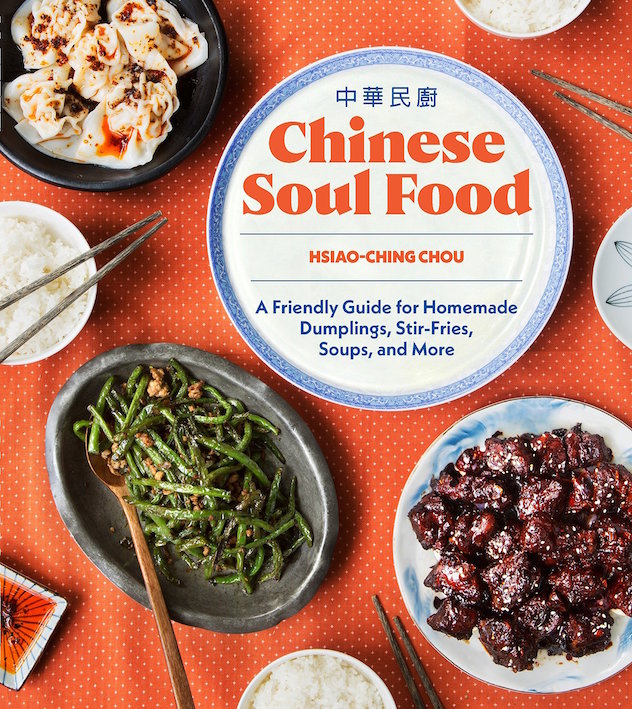

Hsiao-Ching Chou’s “Chinese Soul Food” speaks to that spirit, as her 80-plus recipes highlight “Chinese food for the soul,” i.e. traditional dishes she considers part of the American comfort food corpus. That includes everything from soup dumplings to kung pao chicken, mapo tofu to long life noodles. She doesn’t define what qualifies as comfort food but I assume familiarity is key, as is emotional connection. I’m familiar with Chef Boyardee spaghetti — latch-key kids know the deal — but that’s not comforting to me like a bowl of spicy beef noodle soup can be.

These are questions Chou has pondered since childhood. A food columnist turned blogger turned cooking instructor, she grew up amidst the steam trays of her parents’ Chinese restaurant in Columbia, Missouri. She includes several of the buffet’s greatest hits, including Twinkie-sized egg rolls, sticky-sweet General Tso’s chicken and that tiki bar classic: crab rangoon. In years past, those dishes could have constituted the core of a Chinese cookbook, but Chou consigns them to the back, labeled as “Guilty Pleasures.” Also, while older cookbooks are filled with Cantonese dim sum or seafood recipes, they are in short supply in “Chinese Soul Food.” Instead, if there’s a broad sensibility to Chou’s book, it’s what she calls the “intertwined regional traditions” found in many Chinese American restaurants today.

“Chinese Soul Food” doesn’t explain this history extensively, though Chou hints at it in writing that her family’s palates “were shaped by war.” Her parents were born in China but fled to Taiwan after the Communist Revolution of 1949. This cohort, which included my own parents, became known in Taiwan as waisenren (literally, “outsiders”). They didn’t just come over with families, they also brought along food traditions from all across China. When U.S. immigration policies finally opened up in 1965, this generation uprooted themselves again to immigrate here, bringing those foodways with them.

Immigration waves from Taiwan, Hong Kong and China reshaped the Chinese culinary landscape, introducing new regional styles such as Hunan, Sichuan, Shanghainese, etc. However, since most businesses couldn’t afford to be too specialized, many also borrowed popular dishes from one another. In Chou’s family restaurant, this phenomenon happened in reverse. While their buffets were filled with those Americanized “guilty pleasures,” her parents insisted on keeping some Sichuanese menu items such as “dry-fried green beans, fish-fragrant eggplant … dishes my parents liked that reminded them of home.”

“Chinese Soul Food” embraces a similar regional diversity. Chou includes recipes for pork and shrimp shao mai, a Cantonese classic, but she also writes about the Taiwanese staple, three-cup chicken, as well as lion’s head meatballs, which arrived in the U.S. via Shanghainese restaurants. These “intertwinings” are everywhere now; looking at her table of contents was like browsing the menus at countless Chinese restaurants in L.A.’s San Gabriel Valley. It’s hard to give that sensibility a specific name — “post-1965 immigrant Chinese cuisine” isn’t very catchy — but it feels real enough.

To be clear, Chou didn’t pen a manifesto for The New Chinese American Cuisine. The book primarily aspires to be a practical guide for accessible Chinese cooking, complete with full-page color photos for reference. Chou wants to demystify — and in a sense, de-exotify — these dishes by teaching home cooks that “any kitchen can be a Chinese kitchen.”

To that aim, she does a credible job slimming down the number of required ingredients and steps of many recipes. I found her red-braised pork belly — a savory, unctuous favorite of mine that I’ve tinkered with many times — to be smartly simplified and easy to follow. On the other hand, some dishes, such as her smacked cucumber or chicken with snow peas, ended up tasting rather one-dimensional, and I wondered if streamlining came at the cost of flavor.

Ironically, one of the dishes my family thought was most satisfying came from the “Guilty Pleasures” chapter: beef with broccoli. It was quick and simple to make and tasted far better than the version you’d get at most fast food franchises.

I turned to “Chinese Soul Food” precisely because I didn’t have family traditions to draw on and now, here I was, using it to cook for my own family. Perhaps my 13-year-old will grow up with some of Chou’s recipes informing her own familiarity with Chinese cuisine, and those flavors and preparations will be how she remembers “Chinese food for the soul.”

Oliver Wang (@oliverswang) is a professor of sociology at CSU-Long Beach, and writes on food, music and culture. This column is dedicated to the memory of Jonathan Gold.