Saturday marks 25 years since the Los Angeles riots tore through countless communities and lit the city on fire.

The uprising followed mounting tensions — surrounding economic disparity in South Central Los Angeles, as well as racial discrimination — following the acquittal of police officers involved in the brutal beating of Rodney King, as well as the shooting of a young black girl, Latasha Harlins, by Soon Ja Du, a Korean immigrant and convenience store owner.

By the end, more than 50 had lost their lives, and 2,300 more were injured. Thousands more businesses, most of them Korean-owned, suffered damage. The fire department received more than 5,500 structure fire calls. Sixteen thousand were arrested. The bill for total property damage came out to more than $1 billion.

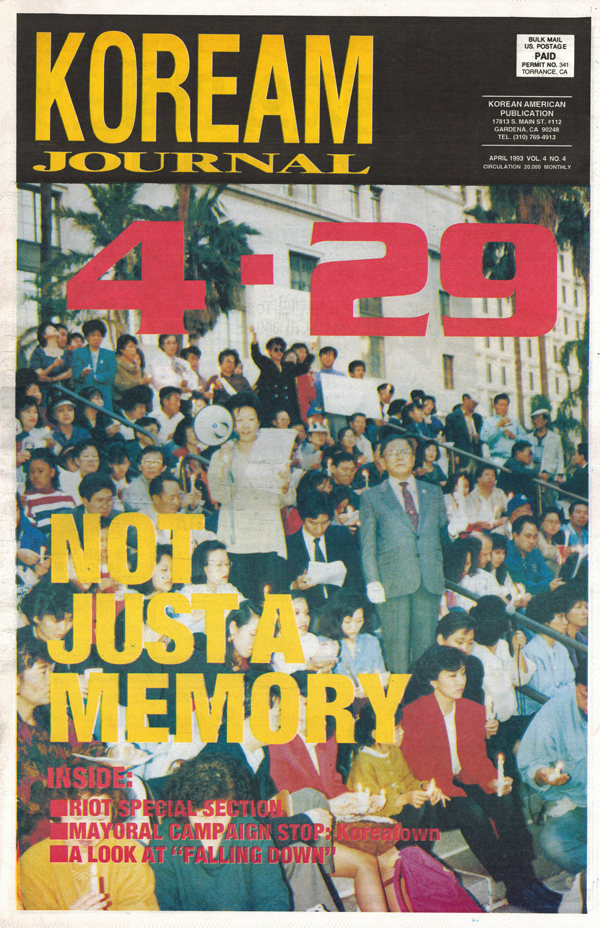

The Korean and Korean American community remembers the tragedy as Sa-i-gu, literally meaning 4-2-9 — April 29.

Here are glimpses at the Korean American community’s reaction to the aftermath and lasting effects of Sa-i-gu, from Kore’s archives.

Koreatown property on fire during the L.A. riots in 1992. (Hyungwon Kang/Kore file)

A strip mall on Western Avenue and Sixth Street in Koreatown is overtaken by fire. (Hyungwon Kang/Kore file)

In a column for KoreAm Journal in 1993, John H. Lee, a Los Angeles Times reporter, wrote on the Korean American stories the mainstream and broadcast media missed in their coverage:

“Jung” is a Korean word describing the force that bonds humans to each other. It’s one part love, equal parts affinity, empathy, obligation, entanglement, bondage and blood.

It is out of a sense of jung, that we share each other’s pain. The emotional drain of seeing arsonists and looters wrack my Koreatown is something I suffered along with virtually every sentient Korean American in Los Angeles.

If I took the feeling of loss after Olympic Market burned, multiplied it by more than 2,000 — the estimated number of Korean American-owned businesses damaged by rioting — then compounded the feeling with the bitterness that comes from knowing the destruction was deliberate, I would come close to describing how Korean American victims feel about the uprising. Never have I felt such soul-yanking jung, as when I reported on the victims’ plight, and on the people who responded to their pleas for help. …

As the city began to sweep away reminders of the riots, funeral services were held for a son of Koreatown, killed in the crossfire of the first night of violence. Eighteen-year-old Edward Song Lee was struck down as he responded to a report of looting at a Korean restaurant on Hobart Avenue.

A young man carries a framed photo of Eddie Song Lee, the lone Korean American casualty of the riots. (Pacific Ties/Kore file)

Prayers for Lee expressed the grief suffered by his parents, two garment vendors living in Koreatown. The sense of loss was shared by more than 5,000 Koreans who crowded Ardmore Park in Koreatown to pay their respects.

“This turnout is the quiet way Koreans are telling the world we are going through a lot of pain,” said Chris Chang, 33, a San Fernando Valley computer analyst who, like most, did not know Edward. “We don’t want to make this political,” he said, “but we want the police and the politicians to know we were abandoned.”

I followed the limousine that would carry the casket to the burial site. Quietly, the six young pallbearers did their duty, with thousands of onlookers clearing a swath for the procession to pass. As the limo pulled out and I walked alongside, I tried to remember exactly how the Korean folk saying went … When parents die, they are buried in the earth. If your children die, you bury them in your heart.

Before she entered a limousine, a heaving Jung Hui Lee clutched her son’s photo to her chest. …

“Jung” haunts me. As do the words of Jihee Kim, niece of a Koreatown shopkeeper who lost his 15-year investment in the riots: “You have to explain how we feel.”

An estimated 2,300 Korean American-owned businesses were looted, damaged or completely destroyed. (Kore file)

Thousands march for peace. (Hyungwon Kang/Kore file)

In 1994, Joon Fong, of the Asian Pacific American Legal Center of Southern California, as a part of a series on the affected, wrote in the Journal about one business owner who saw his hard-earned South Central Los Angeles convenience store burned to the ground:

David Kim (not his real name) felt that life was unbearable. All he remembers after jumping out of a speeding car on the Santa Ana Freeway is waking up in a hospital emergency room with doctors and nurses hovering over him. He had suffered a broken neck and ribs. The bone in his calf had shattered and had to be replaced by a piece of plastic. It was a miracle that he survived at all. His desperate act was the culmination of all the frustration, anger and hopelessness he had endured since the Los Angeles riots two years ago. …

Out of desperation, Kim started a retail toy business from the back of his car. He went back to cleaning apartments as a janitor. Mrs. Kim returned to waitressing. … Still, it was not enough and they sank deeper and deeper into debt. … The Kim’s situation was exacerbated by the City’s ordinance banning certain liquor stores from reopening in South Central unless the owners complied with harsh restrictions.

“We work 120 hours a week from dawn to dusk, live frugally to send our children to college, and contribute to the economic well-being of the community,” said Kim. “Yet we are treated like criminals. It isn’t fair.” …

Incredibly, Kim still wants to rebuild his business and return to his old location. … Kim feels a strong attachment to the community and feels an obligation to the locals. “The elderly people must walk a long way to get groceries because my store is closed,” said Kim. With downcast eyes, he whispers, “I want to go back.”

Korean American businessowners took to protecting their own properties from looters and arsonists. (Hyungwon Kang/Kore file)

KoreAm Journal, April 1996. (Kore file)

In the Journal in 1996, for a special feature titled “Silent Voices No More,” Steve Yoon wrote:

To an outside observer, this city might look as though it has made a complete recovery. And on the surface, besides a few empty buildings, it has in many ways healed itself. … And the blood that was spilled on that day has been washed away by the rain. But what about the people? Have they been healed of their wounds? Have they rebuilt their minds and souls? …

The only thing that holds true is that we as a community can no longer be passive with our role in this country. Racial tensions, left alone, will not go away but will instead fester in our minds like an infectious disease. We’ve learned the hard way that, in this country, silence kills. In Asia the nail sticking out gets the hammer, but in this country the squeaky wheel gets the grease. In order to survive in this society, we must demand our rights or our rights will be ignored. We must explain how our culture works so that others will be able to work with us and not against us. We must shout out our protests against the laws and regulations that stop our community from growing. But more than this we must let the world into our hearts so that we will be known as human beings first and Korean Americans second.

National Guard patrol at a Koreatown grocery store. (Hyungwon Kang/Kore file)

Angela Oh leads a rally at Los Angeles City Hall in 1993. (Kore file)

Angela Oh, a Korean American teacher, attorney and activist who acted as a spokeswoman for the community following the riots, echoed Yoon’s statement a year later.

Korean Americans in Los Angeles experienced a brief moment of unity. Some 40,000 people from all parts of Southern California gathered at Ardmore Park the week after order was restored during 1992, in the city of Los Angeles. A march which took its course through the area known as Koreatown was moving, unified, strong and defined. The message was clear: Korean Americans in Los Angeles (along with many others), from all walks of life, will come together to ensure the suffering inflicted upon thousands of innocent families will be eased. We have failed. …

Where are we headed? It seems everyone is trying to assess what has been accomplished in five years. [Data] is valuable, but we must realize the data will never keep pace with the reality of the unfolding Korean American story. … The impact of the riots on Korean Americans is emerging every day. It will take at least a generation to penetrate the institutions that serve as the foundations of our society and to weave the experiences of Korean Americans into the consciousness of this country.

The most meaningful thing Korean Americans can do during the fifth anniversary of the riots is to acknowledge that little relief was brought; and, to commit ourselves to staying informed and involved in our community. While this may sound unimpressive (certainly not as glorious as holding a rally or hosting a huge ceremonial event), it is without a doubt the most difficult path to walk because there are so many reasons not to remember the pain, humiliation and price paid by more than 2,500 Korean American families in 1992.

A rally and march was held in Koreatown for the 10th anniversary of the riots. (Kore file)

Snapshots from the 10th anniversary rally and march. (Kore file)

John H. Kim returned to write for the Journal in 2002, the 10th anniversary of the riots, with a reflection of his role — as well as that of his employer, the Los Angeles Times — in the riots:

[When the Riots broke out], I had a sinking feeling that the Times, of all the outlets for news, should have seen it coming. Worse, I felt our coverage (and omissions) inadvertently laid the foundation for discontent. And those fallen residents, merchants and innocent bystanders were the embodiment of the sort of misguided and volatile reportage that appeared under a Times byline. …

Over time, news becomes history. I am resigned to this fact, and that in the case of the Riots, the accounts that stand the test of time might not be those spit out under tight metro-daily deadlines or by the “gee-whiz” news weeklies.

For Korean Americans, the truth about the Riots is still trickling in, after having been squeezed and filtered through the same cracks between which the all-but-forgotten have long since fallen.

A view of Vermont Avenue in Koreatown, with smoke clouds in the background. (Hyungwon Kang/Kore file)

Another reporter, Erin Aubry Kaplan, who wrote for the Times’ now-defunct City Times section and who remains an op-ed contributor, remembered the riots as a wake-up call in 2002:

Everybody was diminished by indiscriminate anger that day — the white truck driver Reginald Denny who was pulled from his cab and beaten senseless; my sister who was menaced by mobs as she drove home from work because she’s light-skinned enough to look white; myself and a teacher friend who drove down to First African Methodist Episcopal Church to attend a peace rally that afternoon, only to be driven away by a literal groundswell of threats and violence that made it clear there could be no peace or temperance that day.

And it was clear that racial hostility and economic hostility were so bound together by the troubles of the past and the impulses of the present; it was impossible to parse the difference. If you had asked looters if they were taking things because of racial grievances or material grievances with Koreans or with anyone else, or because they had no perceived stake in their surroundings, you wouldn’t have gotten a single answer.

Children march past burned-down property in Koreatown. (Estelle Chun/Kore file)

Another 10 years later, reverberations of the riots still rang loud.

Radio Korea’s Richard Choi, who was an announcer when the riots broke out, told the Journal in 2012 that he saw the uprisings as the birth of Korean America:

Los Angeles’ Korean community, as we know it, started in the mid-1960s. And after about 30 years of that community, they were still living as Koreans in America. [The first generation] didn’t care about America. They thought of themselves as Koreans, not Americans. But after the L.A. riots, after that, people started thinking if they want to survive in America, we can’t just live as Koreans. We have to become Korean Americans. So after the riots, there was a lot of bad, but this was one good thing.

Journalist K.W. Lee visits the grave of Eddie Lee with Lee’s mother on the seventh anniversary of the riots. (Courtesy of K.W. Lee/Kore file)

Veteran journalist K.W. Lee, who has long been called “Korean America’s community conscience,” described, in 2012, the inspiration he received from the death of Eddie Lee. It is up to the grandchildren of those damaged by the riots, he argued, to “restore truth, honor and humanity to the nameless and faceless 4.29 victims.”:

I hear Eddie, a child of Koreatown under siege, beckon, “If you don’t speak up, who else will?” …

Remember, grandchildren of 4.29. It was the English-speaking children of 4.29 victims, in their teens and twentysomethings who, along with their voiceless immigrant parents, almost overnight organized the nation’s largest Asian rally and march of more than 30,000 demonstrators, with a sprinkling of young blacks, Latinos, Asians and whites the weekend following three days of fires, chaos and violence. …

I can only hope that you, too, hear our fallen Eddie Lee beckoning: If not you, then who?

How do you or your family remember April 29, 1992? Comment below.