Not Good Enough to Play Ourselves?

A casting controversy at the prestigious La Jolla Playhouse reignites the debate on fair representation on stage.

story by Chelsea Hawkins

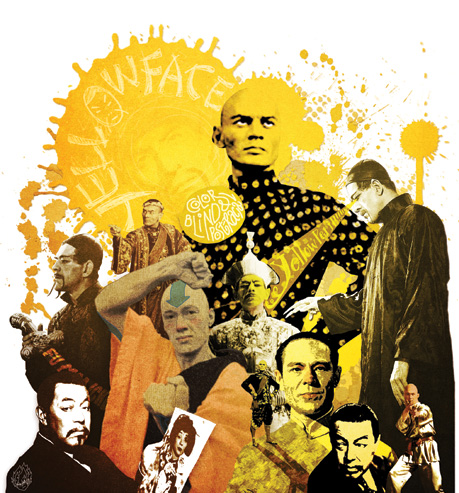

illustration by Inki Cho

While we’ve seen an increase in Asian Americans in television and films — John Cho, Lucy Liu and Maggie Q, to name a few—the face of theater remains the same. The silver and small screens are better reflecting the growing diversity of our communities, but the stage remains alarmingly monochromatic.

In the last five theater seasons, less than 2 percent of roles on Broadway were given to Asian Americans—that’s only about 54 of 3,530 roles. In nonprofit theater, only 3 percent of roles went to Asian American actors. Asian Americans overall saw a decrease in their numbers in mainstream theater; during the 2009-2010 season, Asian Americans were seen in only 1 percent of roles in Broadway and nonprofit theater combined.

Caucasian actors, meanwhile, got about 80 percent of theater roles.

It’s no secret that people of color, including Asian Americans, lack adequate representation in mainstream media and American pop culture. It’s known, although not necessarily acknowledged.

But last month, when the La Jolla Playhouse decided to stage a version of The Nightingale, a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen set in imperial China, while subtracting the Chinese cast, the issue was staring us in the face. As a community, Asians and non-Asians were forced to tackle not-so-easy-to-answer questions on race, ethnicity, cultural appropriation and equality.

Why were only two actors of the 12-member cast Asian American? Why was this viewed as acceptable? And what can we take away from the La Jolla Playhouse casting controversy to insure we, as a community, continue to be seen on stage?

This isn’t just about La Jolla Playhouse — they made a mistake and have been willing to engage in conversations about their decisions—but this is a problem found throughout the theater world.

Tim Dang, artistic director of the Asian American theater company, East West Players in Los Angeles, said the issue is a two-fold problem. First, Asian Americans do not fill the administrative seats in most mainstream theaters, and secondly, Asian American stories are not seen as profitable to many theater overseers. “Who is deciding which story is to be heard or experienced? That’s where we have this initial glass ceiling,” he explained. “Because we don’t have enough Asian Americans in authoritative positions in theentertainment industry … in those creative positions, to make decisions to green-light, to say ‘I like this multicultural piece,’ or ‘I like this Asian piece.’”

“Who is deciding which story is to be heard or experienced? That’s where we have this initial glass ceiling,” he explained. “Because we don’t have enough Asian Americans in authoritative positions in theentertainment industry … in those creative positions, to make decisions to green-light, to say ‘I like this multicultural piece,’ or ‘I like this Asian piece.’”

But this is not a new phenomenon or the first time white actors have been cast in culturally and racially sensitive roles. About 20 years ago the casting of Miss Saigon drew heavy criticism after white males snagged lead roles, and to add salt to an open wound, wore eyelid tape and face bronzer in order to appear more Asian. It was blatant yellowface, a practice many had thought had been left in the era of Charlie Chan and his fortune-cookie wisdom.

Dang was heavily involved in the Miss Saigon protests and has actively advocated for greater visibility of Asian Americans in theater, television and cinema. He, like many others, says the reason Asian Americans are so invisible on stage and in mass media is because we are the “perpetual foreigner.”

“When people see an Asian face, we are always considered the foreigner,” Dang said. “We need to be able to dispel that myth. … Many of us were born and raised in the U.S., some of us could be fifth- or sixth-generation American and yet there is this perception that we are all foreigners. … We are part of the American scene. People need to recognize that.”

Actress and playwright Christine Toy Johnson serves on the board for the Asian American Performers Action Coalition, a nonprofit group of actors looking to understand and remedy the lack of visibility of Asian American performance artists. Johnson has also served as an officer for the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts, previously known as the Non-Traditional Casting Project.

Johnson and her colleague, fellow actress Cindy Cheung, appeared on a talk-back panel with members of the La Jolla Playhouse, including La Jolla Playhouse artistic director Christopher Ashley, and The Nightingale director Moises Kaufman and casting director Tara Rubin.

During the session Cheung and Johnson called out the casting mishap, demanding to know why the directors made the decisions they did and why they did not reach out to the Asian American acting community. Director Kaufman explained he and the creative team latched onto what drew them originally to the story—the feeling that this was set in a world different from our own. They then built their version of The Nightingale around this.

“If I was setting it in China—if the conceit of all of us had been, ‘We are setting it in China’—then we would cast the entire thing Asian,” Kaufman explained during the panel discussion. Nonetheless, he assured the panel and audience that did not invalidate or take away from the concerns of the Asian American community. “We owe you an apology—we owe everyone an apology—because this was an issue of representation. Because this is a workshop, we were in the middle of figuring it out.”

It is important to acknowledge The Nightingale is a developing work and the current incarnation of the play is not necessarily the finalized version. It’s quite possible, from casting to setting, that when finalized, the play will appear drastically different.

Christopher Ashley has repeatedly defended his decision to cast a predominately white cast as a “multicultural” approach. He told the Los Angeles Times that they had done read-throughs of the script with all-white and all-Asian casts prior to this first casting.

But Ashley has recognized the missteps made and during the talk-back panel he said, “We didn’t intend to offend fellow artists or the Asian American community, and that we inadvertently did so, and we are sorry.” However, discussion is not insular, nor is it only about La Jolla and the current production of The Nightingale.

In a column printed in the Los Angeles Times, Charles McNulty recognized the “inexcusable” lack of representation Asian Americans face, but defended La Jolla Playhouse’s creative freedom.

“Institutions like La Jolla Playhouse need to be reminded that they are underserving entire communities. But those underserved communities need to recognize the right of artists to establish their own conventions of representation,” he wrote. “They should also reaffirm the value of nontraditional casting, even as they are right to point out that it hasn’t yet trickled down sufficiently to their benefit.”

But Cheung has asked repeatedly if this would have happened if it was set in Africa—would a director be willing to replace African American actors with white actors in a play set in a clearly culturally African state?

In an interview with KoreAm Journal, Johnson said the argument of multicultural casting does not hold ground when it comes to the La Jolla controversy. “Non-traditional casting and multicultural casting—those terms have been really misunderstood and misappropriated, especially recently,” she said. “It’s [casting] when race, ethnicity, gender, age and/or presence or absence of a disability are not germane to the character or the play’s development.”

Johnson continued, explaining, “Where it’s been misunderstood, it was never meant to give more opportunities to people who have historically had more opportunities than anyone else, e.g. Caucasian males. It was never meant to give Caucasian people the opportunity to play racially specific or culturally specific roles.”

Johnson, who saw La Jolla Playhouse’s production of The Nightingale said, point-blank, “It hurt.”

“There was so much taken from Chinese culture, that I didn’t understand,” Johnson said. “If it had been set in a mythical place where there was a real true mix of cultures, I would have been more open to the whole concept, but to me? I just didn’t see it. … The design and the names of the characters [were Chinese] … there was even a page in the program about the Forbidden City and about the emperor of China.” Her voice tinged with sarcasm and a little frustration, Johnson later asked, “Are we not good enough to play ourselves? Is this the message you want to be sending out?”

Johnson points out that there has never been a play produced on Broadway written by an Asian American woman. “And, I believe there has only been one play produced on Broadway by an Asian American man,” she said, then paused and added, “I may be wrong but if I am, I’m off by like one.”

The numbers are alarming to Johnson and her colleagues and illustrate a field that has blatantly neglected Asian American actors. The problem Johnson has found is that Asian Americans are perceived as the “perpetual other.” They are not even considered for roles since they are not seen as truly American.

“I’ve never met any Asian American person, of any generation, who has not been complimented on how well they speak English at some point in their life,” she said. “That just speaks to that perception that we can’t seem to break through.”

The problem, ultimately, is the business of theater itself. Dang explains that theater “seems to be behind the curve” when it comes to inclusion and representation. The reasons are multifaceted: films are international and there’s a wider audience; a wider audience means a bigger pool of possible ticket buyers. Theater is limited by its locality and the immediate community, and a theater has a smaller number of patrons so they’re going to kowtow to what it is they believe the customer wants. It comes down to the almighty dollar: who has it, who is going to spend it and what the customer wants.

Dang uses television commercials as an example, lauding them as incredibly diverse. But why are they so diverse? Because they know their customers aren’t only older, Caucasian males.

“We are a viable market,” Dang said. If the community wants to see change, he asserts, we need to “speak up” and support our artists and performers. “If you want our dollars, we better see representation in the work you put on stage or in film or on TV. In other words, we can talk with our wallets.” But until the business and administration of theater changes, Dang said, “We are still invisible.”

This article was published in the September 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the September issue, click the “Buy Now” button below.