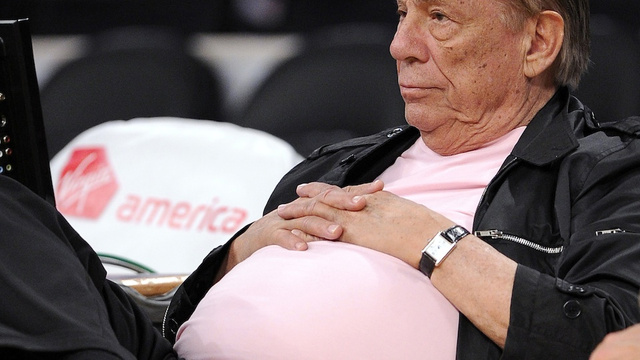

Tuesday’s column on Slate about Donald Sterling, the disgraced Los Angeles Clippers owner, reveals what his “fondness” of Koreans means to the broader pattern of racism in America.

Sterling, 80, was suspended indefinitely by the NBA recently after the recording of his remarks to his girlfriend about his disdain on blacks and how he didn’t want her to bring them to Clippers game caused a public outcry.

[ad#336]

In 2002, Sterling was sued for allegedly discriminating against black and Hispanic housing applicants at one of his apartment buildings located in Koreatown district of Los Angeles. Sterling had changed the name of the building to “Korean World Towers” and decorated the building with Korean flags. He even allegedly tried to force black and Hispanic tenants out of the building, saying they “smell and attract vermin.”

To Sterling, the column suggests, Koreans were the “ideal” tenants. He allegedly said that Koreans “will live in whatever conditions and still pay the rent without complaint” and told one of his former non-Asian female employees that she should “learn the ‘Asian way’ from his younger girls because they knew how to please him.”

The column’s co-authors, Hua Hsu and Richard Jean So, wrote that Sterling’s preference for Koreans and Asian Americans fits into the typical pattern of racism in America:

Why did Donald Sterling love Koreans? At a basic level, he was buying into the myth of the “model minority”: the perception that Asian-Americans, compared with other nonwhite minorities, are innately intelligent and well-behaved.

This will all sound very familiar to Asian-Americans, cast as the put-upon overachievers, whose head-down, by-the-bootstraps stoicism has resulted in remarkable educational andfinancial attainment. The “model minority” myth persists in part because it is cited as evidence that the system works. It makes for a great story—the plucky, determined Asian-American succeeding where others have failed. But the ultimate beneficiaries of this racial typecasting are the people who invoke the model as a bludgeon against others. Sterling’s admiration for his Korean tenants is actually a kind of scorn. After all, he still subjected Korean tenants to the same degrading treatment as everyone else—the only difference is that the Koreans seemed willing to take it.

Above all, Sterling saw the world in terms of winners and losers (“I like people who are achievers,” he once noted), and he used this logic to categorize racial groups along a sliding scale of desirability. For Sterling, Koreans never merited the decency of being looked upon as individual human beings. Rather, they were a faceless bloc, a group of indistinguishable “achievers” that did nothing more than provide the contrast that enabled his contempt for blacks. This is the lesson of Donald Sterling’s racism: A hierarchy that flatters those at the top and demeans those at the bottom can only serve to distract us from noticing the one shuffling the rankings.

[ad#336]