You know when you see a Noguchi coffee table. It’s comprised of three simple components: two vaguely boomerang-esque wooden pieces whose pointed ends touch, balancing an incredibly heavy triangular glass tabletop. This is the thing that Isamu Noguchi is most famous for. My entire life I thought Noguchi was a Japanese artist and designer who made modern furniture and huge sculptures for public spaces and office courtyards. I was shocked to discover that Noguchi was actually a Japanese American hapa born in Los Angeles County Hospital in 1904 and who lived until 1988.

Back then, a mixed-race baby was so unusual that the Los Angeles Herald reported his birth. His father, Yone Noguchi, a famous Japanese poet, had loved and left Noguchi’s white American mother, Léonie Gilmour, while she was still pregnant. She had literary aspirations and worked as a typist, stenographer and bookkeeper. They lived in a tent in Pasadena. He never wore shoes, played in the nearby stream and went by the name Baby.

When he was around 5, he and his mom moved to Japan to be closer to his father, who would then give him the name Isamu. With his bright green eyes, Caucasian features and white mom, little Noguchi did not fit in with his classmates. Nevertheless, he absorbed a lot about Japanese culture and aesthetics and fell in love with its beautiful countryside. Concerned that he was too girl-crazy, Noguchi’s mother found a progressive boarding school, Interlaken School in Indiana, and convinced him to apply. He left Japan by boat alone at the age of 13 to return to his homeland, America.

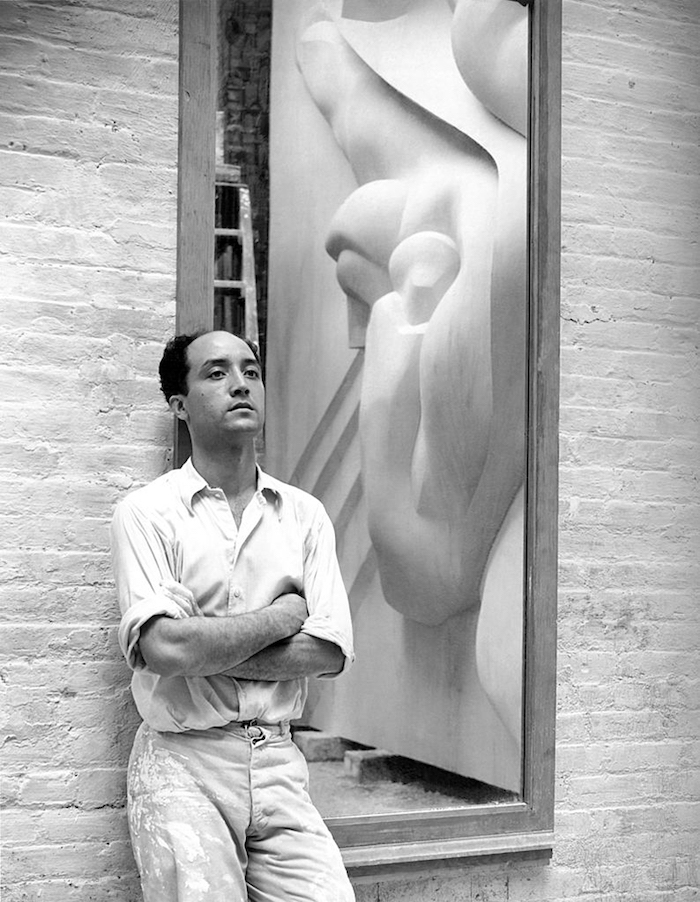

By the time World War II rolled around, Noguchi was a famous and established artist who hung out with contemporaries like Constantin Brâncusi and Arshile Gorky. His lovers included Frida Kahlo and Tara Pandit, the niece of Jawaharlal Nehru, the prime minister of India. He was briefly married to the movie star Yoshiko Yamaguchi. Inspired by Diego Rivera, he created a huge steel mural for the Associated Press that reflected the noble work of everyday journalists. He designed stage sets for the legendary modern dancer and choreographer Martha Graham. Noguchi was hardworking, brilliant and passionate about social justice. He used his art to question imperialism, nationalism and capitalism.

When Executive Order 9066 was issued, he reached out to the Japanese American community and organized to improve their war-torn reputation. He mistakenly thought that internment could be an opportunity to design a utopian community and volunteered to enter a concentration (terminology intended) camp in Poston, Arizona, to help prepare for the incoming internees.

But the internees regarded him with distrust because he seemed to be part of the administration. Meanwhile, the authorities thought Noguchi was just another Japanese internee, never implemented his plans, and refused to let him leave. In his seventh month of imprisonment, he managed to obtain a letter from a government official allowing him a leave of absence, and he never returned to the camp.

The sculptures he made after his internment were embittered and desolate, such as a thick column, festooned with wooden dowels and human bones, and a hanging African American man writhing in agony.

Throughout his life, he felt completely alone and struggled to find a community not just among artists but also the Nisei, spiritual seekers and whoever didn’t fit in with the rest of society. Restless, he traveled all over the world and absorbed various artistic traditions in Greece, India and Southeast Asia. Most of his art, which was constantly shifting in medium and style, was about interrogating the duality of his identity: East versus West; East and West; East or West.

His profound loneliness led him to find solace in his quiet and contemplative artworks made of stone, like the serene Noguchi Garden in Costa Mesa, Calif., and reflected a movement towards the reconciliation of both identities. I think that he discovered— as many Asian Americans do about belonging and not quite belonging to two diametrically opposed worlds— that the cause of his greatest pain was precisely the source of his power.

This article appeared in Character Media’s August 2019 issue. Subscribe here.