I was visiting my aunt in Little Saigon when I first saw her collection of “Tintin” comic books. A souvenir from her childhood in the real Saigon, they’d been sitting on a shelf collecting dust for several decades. I’d never enjoyed comics before (more of a “Magic Tree House” kid), but within the first few pages I was hooked. I read the whole collection over the course of the next few months, carrying them back to my then-hometown of Winnsboro, South Carolina.

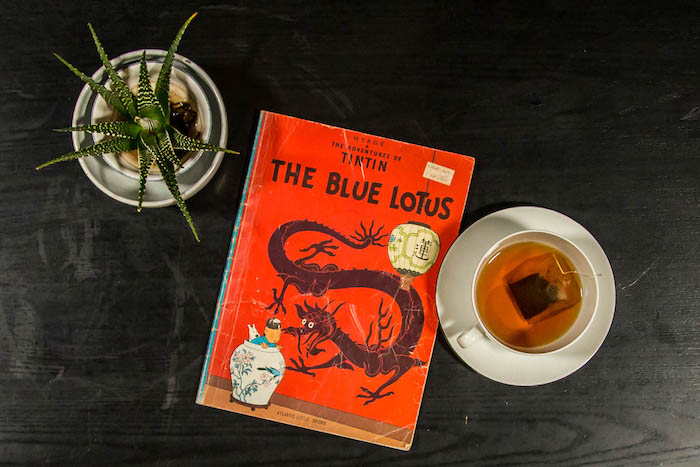

It turned out my aunt and I shared the same favorite book in the collection: “Tintin and the Blue Lotus.” Originally published as a black-and-white serial between 1934 and 1935, the full comic album sees the famous boy reporter and his dog Snowy traveling to Shanghai to meet a mysterious Japanese man named Mitsuhirato. In typical “Tintin” fashion, nothing goes according to plan. Mitsuhirato turns out to be a treacherous character who makes several attempts on Tintin’s life, and the story is full of nail-biting action scenes and Tintin’s daring escapades as he takes on opium lords, bullying Western businessmen and scheming politicians.

It’s no secret that Belgian author Hergé’s (born Georges Remi) illustrations of ethnic minorities haven’t aged well. African characters are drawn with thick red lips and ink-black skin, and the sword-wielding Asian characters in “The Blue Lotus” have squinty eyes, jutting cheekbones and buck teeth. And yes, the story does have some Orientalist undertones. Tintin gets a visit from a superhuman fakir, multiple people lose their sanity after infection with something called “Rajaijah” (“The poison of madness!”) and a Japanese character commits ritual suicide at the end of the book.

But Tintin’s adventure in China differs from his other forays into non-white lands. Hergé uses “The Blue Lotus” to debunk a number of myths about Chinese people and customs—often at the expense of Westerners, who are portrayed as ignorant and boorish. The Asian characters of “The Blue Lotus” are depicted with emotional complexity, as loving parents, honorable friends and skilled professionals. Tintin and Snowy are quick to run off a rude European man who abuses a rickshaw driver, and twin British policemen Thomson and Thompson (who appear as buffoons in a number of “Tintin” comics) draw laughs from Chinese villagers after dressing themselves up “in disguise” with pigtails and ridiculous costumes. The action is punctuated with picturesque illustrations of countryside and cities, showing readers the breadth of the Chinese landscape.

Hergé is famous worldwide, but his perspective can be credited to a little-known Chinese artist: Zhang Chongren. When Hergé was just starting the process behind “The Blue Lotus,” he became fast friends with Zhang, a Chinese student studying in Brussels who urged Hergé to investigate Chinese culture and customs rather than dismiss them. Hergé, fortunately, was receptive to the idea. He once said in an interview that, before he got to know Zhang, media portrayals of the then-recent Boxer Rebellion led him to believe that “China was peopled by a vague, slit-eyed people who were very cruel, who would eat swallows’ nests, wear pigtails and throw children into rivers.”

As thanks to his friend, Hergé named one of his characters, Chang Chong-Chen, after him. An orphaned Chinese boy, Chang saves Tintin a number of times throughout the comics. When they first meet, the two have a heart-to-heart in which they spill all the stereotypes their people believe about one another. Hergé isn’t ashamed to satirize his own outdated beliefs. Tintin says that many “stupid Europeans” think that “all Chinese are cunning and wear pigtails, and are always inventing tortures, and eating rotten eggs and swallows nests.”

The cultural history surrounding “The Blue Lotus” was, of course, lost to me when I first read the book as a kid. In South Carolina, I didn’t grow up watching anime or “The Last Airbender,” so aside from the rare, vague portrayal on the Disney Channel, “The Blue Lotus” was one of the few access points I had to Asian culture (albeit Asian culture of decades past). In the story, Tintin openly mocks stereotypes that I still, in the early 2000s, had heard at school: that all Chinese women are hobbled by foot-binding, that Asia is racked with poverty and populated by uneducated farmers, etc. Hergé takes great pains in “The Blue Lotus” to show readers that the Western world isn’t much different from “exotic” places like Shanghai, and that’s groundbreaking even today.

My aunt still has the same collection of “Tintin” books on her shelf, her well-worn copy of “The Blue Lotus” sitting on top of the stack. It might be difficult for some to enjoy the story in 2019. But it’s worth it to look past the buck-toothed characters, and appreciate the adventures of le petit vingtième in a now long-gone China.

This article appeared in Character Media’s Summer 2019 issue. Subscribe here.