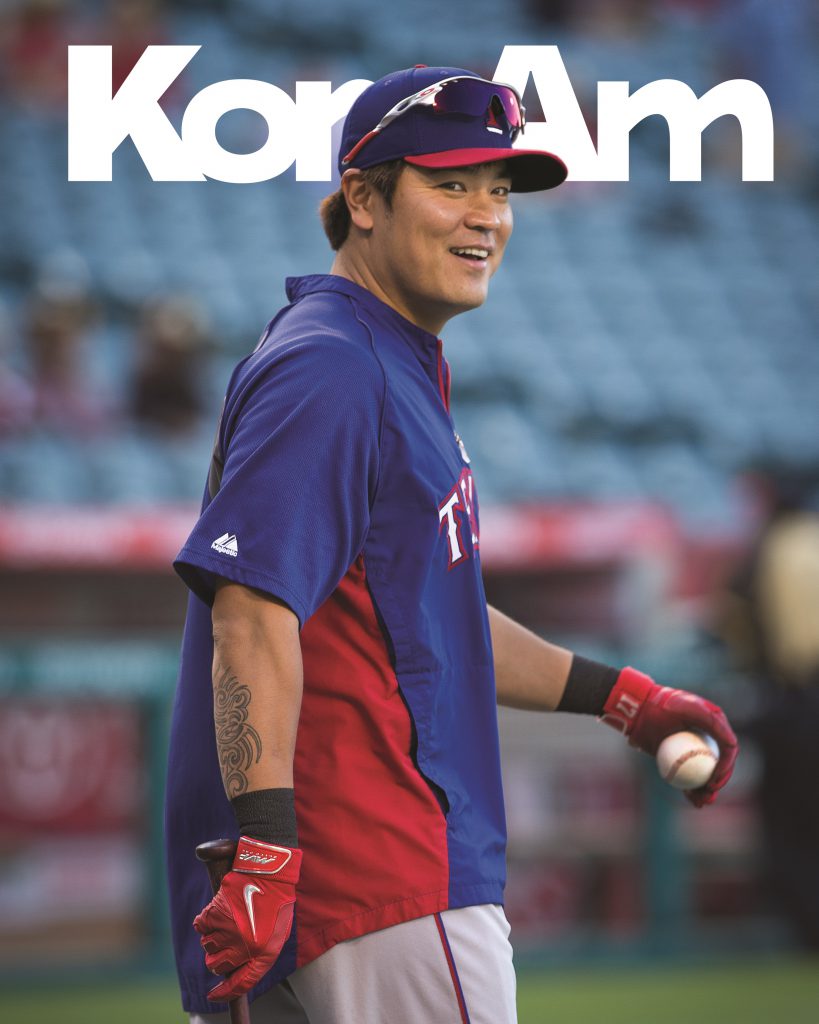

THE CHOOSEN ONE

Texas Rangers outfielder Shin-Soo Choo has proven himself a powerful player, who also commands an impressive multimillion-dollar contract. But what he and his fans are most proud of is the resilience Choo has displayed time and time again, first as an 18-year-old prospect from South Korea coming up through the minors, and now as a veteran major leaguer trying to come back from a challenging season.

written by STEVE HAN

photographs by MARK EDWARD HARRIS

DON’T FALL BEHIND THE COUNT, SHIN-SOO CHOO TELLS HIMSELF.

He’s leading off the sixth inning at Angel Stadium with the Texas Rangers down 2-0. The left fielder gently gnaws on his bubble gum as he walks to the plate. He swings effortlessly to loosen up, enters the batter’s box and sets his feet. Then, he stares in at Hector Santiago, who’s so far throwing a shutout.

Santiago’s first pitch is a 91-mile sinker through the middle. Choo swings hard, smashes the ball and sends it arching toward center field. Angels outfielder Mike Trout runs back, back and back a little more. Trout jumps desperately for the ball, but crashes into the wall and tumbles onto the warning track empty-handed. As the cliché goes, that ball is history. Game on.

Inspired by Choo’s homer, the Rangers come from behind and take a 3-2 lead. In the next inning, Choo rips a line drive to center field to bring in another run to extend the lead. Texas would go on to win, 5-2, giving themselves a 16-13 record, the second best in the American League and only two games behind the Oakland A’s.

A month into the 2014 season, Choo is looking like the worldly free agent signing he was expected to be for the Rangers. After that May 2 game, he is batting an impressive .325, with a .446 on base percentage.

Indeed, when Choo first signed with the Rangers last December, the front office, Texas media and fans alike all touted him as the final piece of the puzzle—the player who could finally push the perennial underachievers over the top. Instead of losing in the World Series, which the Rangers had done twice in the last four years, the team just might finally bring home their first championship trophy.

Well before his contract with the Cincinnati Reds expired after last season, the Rangers had begun scouting the South Korean native, with the intention of making him their marquee signing. Choo’s ability to get on base (second in on-base percentage last season in the National League at .423), his speed (over 20 stolen bases in four of the last five seasons), and his hitting power (104 career home runs), not to mention his rifle of a throwing arm on defense, made him one of the most coveted free agents on the market. The Rangers competed with none other than the New York Yankees for Choo, who turned down a seven-year, $140 million offer from baseball’s most storied franchise because he felt Texas would give him the best shot at winning.

But it was that very game in Anaheim this past spring when things both got off to such a bright start and yet also began falling apart. After giving the Rangers a 4-2 lead in the seventh inning, Choo left the game with soreness in his left ankle. He hasn’t been the same since. Nor has his team, ravaged by a slew of player injuries.

Fast forward six weeks to June 20, and the Rangers are back in Anaheim. With two outs in the top of the ninth inning, Choo steps up to the plate with the Rangers down by four runs. He swings at Joe Smith’s first pitch, but this time, misses. He swings on the second, and misses again. On the third pitch, he swings even harder—and misses.

Angels win, 7-3. The Rangers, more than 10 games behind the A’s, are now one of the worst teams in baseball.

Tilting his head back in frustration, Choo loiters around home plate before walking feebly back to the dugout, dejected.

* * *

“I CAN’T help it. I don’t have that personality where I just say, ‘Who cares?’ and move on when I play bad. It just doesn’t work like that for me.”

Choo tells me this during a private interview in the Anaheim clubhouse on June 20, a few hours before the disappointing game. He’s referring to past games, of course, though his remarks could easily apply to his performance later that day.

Sitting hunched over on a folding chair in front of his locker, Choo is wearing a blue, fitted, long-sleeved shirt and black fleece shorts, with his Rangers hat pulled down to his eyebrows. Before our interview, he offers a handshake and makes a slight bow, a traditional Korean way to greet someone you meet for the first time. As he speaks, the 32-year-old often pauses for several seconds before answering my questions, as if deeply engaging each one. He comes across as thoughtful, honest and humble—even for an athlete from South Korea, where modesty is expected of public figures. It’s hard to imagine that this is a man who is set to pocket $130 million over the next seven years.

“I know better than anyone that I won’t be a Hall of Famer, ever,” Choo says in Korean. “I’ve heard people say that I’m a five-tool player, but I’m a five-tool player who’s average at all five things. Mike Trout and Andrew McCutchen are the real five-tool players. For me, if people who’ve seen me play just remember me as a player who gave it his all every game, I’d be more than happy with that.”

Those appear to be the words of an athlete who has been seasoned by struggle, hard work and more struggle before tasting success. Out of the 14 years he has lived in the U.S., Choo spent nine in the major leagues and the remaining years bouncing around in the minors trying to prove himself. After signing with the Seattle Mariners in 2000, he would play for seven different teams over a five-year period, before finally getting his first at-bat in the big leagues. Those were humbling years spent living in places like Appleton, Wisconsin, and San Antonio, Texas—cities with no sizable Korean community. Choo and his wife Won Mi Ha, who spoke limited English at the time, struggled mightily in those days—so much so that putting food on the table for their son, Alan, was a challenge.

“There were times when we couldn’t afford a hamburger,” Choo recalls. “I’ll never forget my years of desperation in the minors. I haven’t played well lately, but this is nothing compared to what I dealt with back then.”

Choo also knows full well that he freely—and controversially—chose this more arduous path. Had he stayed in Korea, after all, stardom seemed all but guaranteed.

The burly, 5-foot-11 athlete from the port city of Busan was a promising 18-year-old pitching prospect, with a 97-mile fastball in his repertoire, when his hometown team tried to sign him.

The Lotte Giants offered him a contract with $420,000 in guaranteed money, which would’ve made him one of the highest paid rookies in Korea. Even his own parents told him to take it. (After seeing him at spring training in 2001, they famously told Choo his Seattle teammates were too tall for him.)

It was an all-or-nothing deal. Had he tried and failed to make it in the U.S. and returned home, Choo would have been banned from Korean professional baseball for two years. It’s part of the Korea Baseball Organization’s policy to deter the country’s best prospects from leaving to play elsewhere and shredding the native talent pool.

Choo still left.

“This is how I am,” he says. “Whatever you do, don’t you want to take a chance at becoming the best at it? I wanted to play with the best in the world.”

Choo, however, didn’t anticipate that, when he got that chance with the Mariners, they would turn the hardthrowing left-hander into a corner outfield prospect.

“Our intention was to make him an outfielder from the start,” says Pat Gillick, the former Mariners general manager who signed Choo. “Choo had an outstanding arm. We just thought he was more valuable as an everyday player in the outfield.”

For Choo, the thought of becoming an outfielder never crossed his mind until the first day of spring training.

“I was a pitcher all along,” he says. “But all of a sudden, I was told to play in the outfield. I didn’t know what to do.”

But, in a way, overcoming obstacles would become something of a specialty for Choo—and so would exceeding expectations.

“He had tremendous power,” remembers Steve Roadcap, the manager of the minor league Class-A Inland Empire, which Choo led to a California League title in 2003. “He also ran well. He had the tools. With a lot of kids with talent, many of them have the tools, but they can’t find the toolbox to showcase their talent. Choo wasn’t one of them.”

Still, by 2006, the Mariners would trade the outfielder to the Cleveland Indians for first baseman Ben Broussard, because with franchise star Ichiro Suzuki manning the outfield, earning anything more than a pinch-hitting role for Choo was a mission impossible. He played just 14 games with the Mariners in a season and a half. Little did the team know that Choo would become one of baseball’s brightest outfielders after leaving Seattle.

“Unfortunately, I was already gone when they traded him,” says Gillick. As a team’s top personnel executive, Gillick won three World Series titles, two with the Toronto Blue Jays in the early ’90s and the other with the Philadelphia Phillies in 2008, and he led the Mariners to playoff appearances in 2000 and 2001.

“I can tell you, honestly, I wouldn’t have traded him,” adds the 76-year-old Hall of Famer.

Between 2006 and last year, Choo’s batting average fell below .280 just once in eight seasons and eclipsed the .300 mark from 2008 to 2010. In 2009, he became the first Asian player in the majors to join the 20-20 club, hitting over 20 home runs and stealing over 20 bases in one season. He would go on to be a member of that distinct clique two more times, including last year with the Cincinnati Reds.

“He did all the little things right,” says Matt LaPorta, Choo’s former teammate in Cleveland. “It’s funny because I thought I was an early riser. During spring training, I always showed up at the ballpark at 6 [a.m.], but this guy … when I got there, he was already dressed.”

LaPorta and Choo became close friends. The two would work out together every day at 5 a.m., and invited each other’s families over for dinner.

“We can all work hard, but sometimes, if you don’t have talent, it’s hard to be successful,” says LaPorta. “But he doesn’t take that talent for granted … he commits to his talent. And when you see a guy who’s having success by working hard, I want that success as well. Hard work is contagious. People saw him and said, ‘I want to do what he’s doing.’”

Choo’s success in the U.S. also hinged on how well he could adapt to the American culture, according to Gillick.

“Baseball is the same everywhere,” says Gillick. “Playing the game, being on the field, competition and all that, it’s the same anywhere. But the cultural change is what’s difficult. When a young man like him reaches his potential, we’re not only happy for him, [but] we’re also happy that we made the right decision 14 years ago.”

Choo, however, says he is well received by his peers not because he fit in so easily, but because he always showed that he’s willing to make the effort.

“Even now, my English is not at all that great,” he says. “But one thing my teammates do give me a lot of credit for is that I’m one of very few Asian players who doesn’t have an interpreter.

“To this day, I still mumble and stutter when I’m giving interviews in English, but they respect my efforts. If I can’t explain something, I’ll use my arms and legs to do it. If that’s not enough, I’ll get my dictionary out.”

** *

ENTERING August, the Rangers are in a free fall. With the worst record in all of baseball at 43-65, their post-season hopes are all but shattered. Still bothered by his ankle, Choo is batting just .240, the lowest his batting average has ever been in the major leagues since his 2005 debut.

Yet, despite such woes, Choo remains optimistic. The benefit of having a career like his, dotted with its many stops and starts before finally reaching success, is that it gives him perspective—and a track record.

“He has proven himself,” says Rangers manager Ron Washington. “As long as he’s able to go out there [despite his injury], he’ll come back around. I’m not concerned.” Choo’s fans seem to share this long-range view of the player, whom they respect as much for his perseverance as for his baseball talent.

“We appreciate him because he comes from a background that resonates with the community,” says Ted Kim, the president of the Korean Society of Dallas, which has already organized two trips to Globe Life Park in Arlington to support Choo this season. The group also participated in the Rangers-hosted Korean Heritage Night on July 11, complete with bulgogi, Hite Beer and the Korean national anthem sung by the Wonder Girls’ Yenny.

“When he came from Korea, he was unproven,” Kim says of Choo. “He built his reputation through the minor leagues. He earned it the hard way. That’s what we’re really proud of.”

It’s a hard-won record that Angels’ Korean American catcher Hank Conger, who made his debut in 2010 after spending years in the minor leagues, can fully appreciate and admire. He met Choo in 2010 when he got called up to the majors for the first time and remembers Choo coming up to him to say congratulations. “Just watching him come through the minor leagues, he’s definitely a role model,” says Conger. “Especially because he understands the difficulty of playing in the major leagues.”

Of course, Choo’s biggest fan—the one who has stuck by him through all the struggles, from the early years in the minors to now—has been his wife, and she eloquently captured on her Facebook page last spring what the journey has been like for the couple, who now have three children:

“Exactly nine years ago, I was here while fully pregnant with our first child to watch a Mariners game, because my husband was in camp. He was never a starter, so I waited even as my stomach was aching badly. Whenever the starters were taken off and he came on, I chanted for him off the top of my lungs, and a fan sitting next to me worried that I would give birth at the game.

Today, my man is a proud starter on a major league team and every fan here is cheering him on. The baby I was pregnant with then is now here, chanting daddy’s name, just as I did then. I’m so proud. No matter what obstacles we face or how much happier our lives become in the future, I will never forget. I will never forget what we always dreamed of!”

Choo says there’s only one thing he’s done that’s better than baseball: marrying his wife. “There wouldn’t have been me today without my wife. She pushes me from behind and pulls me from the front,” he says. “She’s given me so much more than I’ve given her. I’m so thankful.”

For Choo, to be able to call himself an everyday major leaguer now, let alone one of the highest paid players on a team with World Series aspirations, is a tremendous sense of pride.

“The road wasn’t easy,” he says. “I rarely admire my abilities as a ballplayer, but I’m hugely proud of what I’ve been through and what I’ve endured to be able to play in these games with these great players.

“My initial goal was to play one game in the big leagues, so for me to have this kind of contract now, getting treated so well and to be where I am … I never thought this would happen, but now I’m here.”

And though he left his native country for a chance to play in the major leagues, he hasn’t forgotten where he came from. He has already laid the groundwork for a foundation that will provide funding for public sports facilities for children in Korea.

“I want Korea to be a place where the most common, and even underprivileged children, have access to ballparks,” Choo says. “It shouldn’t matter if their parents are rich or poor, or if these children are physically disabled. I want to build ballparks that any child can go to and play as much as they want.”

In a way, Choo’s gritty rise to success away from home starkly contrasts the road taken by his fellow countryman Hyun-Jin Ryu, who was heralded as a star even before he threw a pitch in the majors. Years before Ryu joined the Dodgers, he had already become a bona fide superstar back home in South Korea, where he was far and away the best pitcher, perhaps even an all-time great, in the country’s professional league. On the other hand, Choo came to the U.S. when he was still an 18-year-old ragtag amateur, a hillbilly from Busan, a place he says he wanted to escape, because he didn’t want to become a “frog in a small pond.” So even when Choo and his team struggle badly, he knows that better days are ahead. He realizes that things were much worse not long ago. Gaining that wisdom and perspective took years of trials and tribulations, which Choo says he used as “transportation” to get to where he is today.

“It’s not an experience you could buy with money,” he says. “Without that experience, I’d have a much tougher time dealing with my recent struggles, but I’ve made it this far by getting stronger and stronger and stronger. I have what it takes to not break easily.”

Epilogue: Days before this magazine went to print, Choo began to display the resilience that has made him such a sought-after player, going 10-for-25 in six games between August 4 and 10—a streak during which he reached 1,000 career hits with a ninth inning single versus the Houston Astros on Aug 9. On Aug. 25, he chose to undergo elbow surgery to remove a bone spur and has been ruled out for the season.

This article was published in the August/September 2014 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the August/Sept. issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only. Expect delivery in 5-7 business days).