You can count the number of things I don’t know about Korean history and culture on many fingers and toes. Usually, I utilize my standby excuse of “But I’m an Asian American Studies scholar” and then huff and puff about my second generation identity issues.

However, I am slowly but steadily learning more about my ancestral homeland, and more importantly, the issues affecting people of Korean descent.

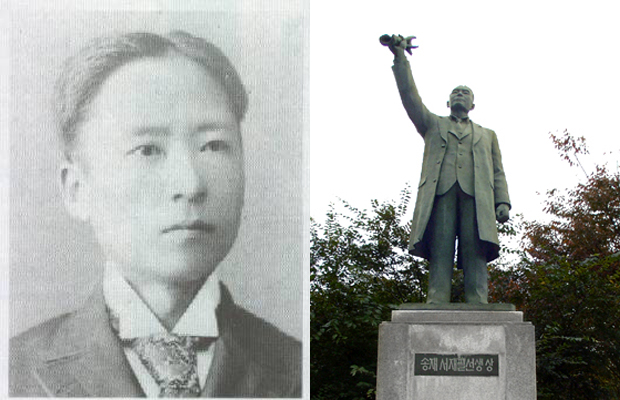

Last year, I attended an academic talk about Zainichi Koreans with my one of my friends who is an East Asian Studies scholar. It was my first time learning about this population of ethnically Korean, multigenerational “outside residents” of Japan since that country’s colonization of Korea, residents who continually face systematic discrimination.

From an informational standpoint, it was an interesting event to attend but in essence, it was a lecture. It wasn’t until last week, from inside a cozy home in the East Bay, that I saw the human element of Zainichi Korean identity and experience. My classmate and friend Kei Fischer invited me to a meeting of Eclipse Rising, a Bay Area Zainichi Korean community organization of which she is co-coordinator as well as one of the founding members along with Miho Kim, Amana Oh, Yongna Ryo, and Kyung Hee Ha. Their mission is to “recognize and celebrate the rich and unique history of Koreans in Japan, promote Zainichi community development, peace and reunification, and work for social justice for all minorities in Japan.”

The diversity of people in the room was amazing: Kei and member Richard Plunk are two hapa Zainichi Koreans who did not discover until later in childhood that they were half-Korean, not half-Japanese as they were led to believe; Haruki Yang-Saeng Pak is half-Japanese and half-Korean but was granted Japanese citizenship through his mother’s side, meaning he has two last names: Eda and Pak. Miho Kim is a third generation Zainichi Korean from Fukuoka, Japan and in 2008 was the first Zainichi Korean to win the Yayori Award for achievement in Women’s human rights work.

Guests included Manami Kishimoto, an activist for the Buraku people in Japan; San Francisco State University Asian American Studies students; members of nihonmachiROOTS , a group of young Japanese American leaders focusing on issues regarding the redevelopment of San Francisco’s Japantown; as well as two visiting guests from abroad: Zainichi Korean brothers from Okinawa who are now in college and graduate school in Japan. Listening to the brothers talk about how the gathering gave them a sense of confidence to be themselves and speak out at school, where they are the only two Zainichi Korean students that they know of, was what really crystallized the purpose of Eclipse Rising for me.

Living under discriminatory policies is only part of their plight; Zainichis are not recognized by either Japan or Korea as legal or symbolic citizens. Language, culture, ethnicity all come into complicated play: ethnic Koreans cannot be granted citizenship in Japan even by birth and to return to Korea is to return to a country whose language and culture are wholly unfamiliar. Stories from Eclipse Rising members reveal that Zainichis of this current generation often face hostility in Korea since their relatives were thought of as “traitors” for moving to Japan to find work and feed their families during colonization.

In addition to learning about Zainichis from a historical and sociological perspective, being at the meeting kept my privilege in check: a clear acknowledgment of my nationality and ethnicity and that of my family and ancestors is something I take for granted. As the beginning of my post explains, there’s so much I don’t know but could know due to an contradictory mix of desire to educate myself and lack of motivation to get started. But, perhaps the most significant impression left on me was an urge to keep deconstructing and reconstructing what it means to “be Korean.” I don’t think Korean identity is something that can necessarily be quantified or qualified in so-called definitive ways: vocabulary, names, or what country issues your passport.

We’re descendants of passionate, proud people, and I like to believe that within that collective spirit, there’s room for difference: different identities and different histories that are all a part of the Korean consciousness.

If you would like to learn more about Eclipse Rising, their events, and how you can contribute, visit their website or Facebook group page.