story by CHELSEA HAWKINS

photography by THOMAS PARK

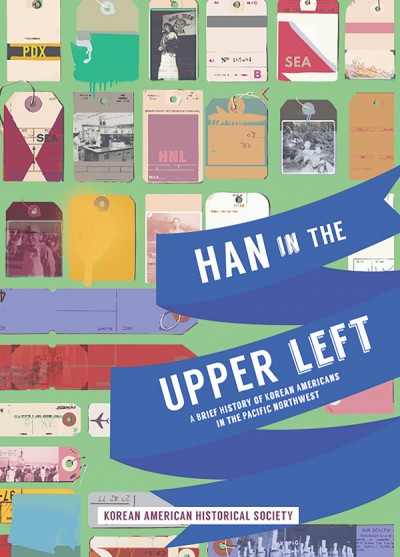

It’s difficult to not be intrigued by the title: Han in the Upper Left, a broad and ambitious book that looks at the history of Korean Americans in the Pacific Northwest. The title references the Korean word for deep sorrow and longing—han—and combines it with a nod to the lyrics of the Seattle-based Blue Scholars, who rap about being “secluded in the upper left” corner of the U.S. The latter allusion to the outspoken, politically charged hip-hop group hints at the fact that this book is no dry, scholarly text.

Indeed, Moon-Ho Jung, the editor of Han in the Upper Left, will tell you outright that this lithe, but substantive, 100-page paperback has an agenda.

“Every book or every piece of historical scholarship is either politically motivated or has a political message,” said Jung, an associate professor of history at the University of Washington. “So we definitely wanted to make an argument through the book, not simply try to document our past, but to frame it, interpret it.”

Jung, along with the Korean American Historical Society, unveiled Han in the Upper Left during a June 4 launch party at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum. The book’s release coincides with the museum’s exhibit, Bojagi: Unwrapping Korean American Identities, running through November.

And Korean American identity, in all its diversity and complexity, is the driving question in Han in the Upper Left.

“Who are Korean Americans?” writes Jung in the book. “We are a people shaped by han, a collective sense of suffering, oppression and hardship. Yet we are a people who survived, struggled on. And if we are to survive as a people, we must forge identities and communities that reflect our history.”

From L to R: Matthew Benuska of the Korean American Historical Society, its founder Ick-whan Lee and Han in the Upper Left editor Moon-Ho Jung.

From L to R: Matthew Benuska of the Korean American Historical Society, its founder Ick-whan Lee and Han in the Upper Left editor Moon-Ho Jung.

Drawing from newspapers, old documents, oral histories and original research done by the Korean American Historical Society, Jung, the society’s president, tries to trace that vast history, starting with how and why Koreans came to settle in the western North American region. The story of Koreans in the Pacific Northwest—an area including Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Western Montana—is closely linked to those of Korean Americans elsewhere in the western U.S. Many of the first Koreans to the Seattle area came from the sugar plantations of Hawaii in search of better lives on the mainland. But these migrants found themselves once more working as laborers on the Great Northern Railway, or for salmon canneries further north, or even back in the fields harvesting fruits and vegetables. Like many of the East Asian immigrants to the western U.S., these early settlers were predominantly male. Many women would come later as “picture brides.”

Old photographs and other archival material pepper the book and help bring the narrative to life. One eye-catching image is a black-and-white newspaper clipping showing a smiling Korean woman and her American military husband.

Taken from a 1951 edition of the Seattle Daily Times, the headline reads, “First Korean War Bride Speechless at City’s Greeting.” Jung explains that this war bride, Yung Soon Morgan, came to American shores with much fanfare and was even greeted by “film star Rita Hayworth and a bouquet of red roses … in what was dubbed ‘America’s traditional family welcome.’” But, upon studying the footnotes, the reader will see that other stories printed around that same time period openly wonder: “Some Aliens May Take Shortcut to Citizenship.” In other words, the seemingly warm American embrace of strangers to this shore was not quite as it seemed.

Later in the 20th century, it was not work in Alaska or on the fields that drew Koreans—it was the university. In the 1940s, the University of Washington was one of the only places where members of the armed forces, preparing for deployment, could learn Korean. This military training course, taught by Korean Americans Harold and Sonia Sunoo, would eventually end, but the two language teachers would become the first to teach Korean at the well-known college. However, despite being well-educated, discrimination against men like Sunoo was still common, and he, like many Asian Americans at the time, couldn’t find housing in the city’s University District. The chair of his department at the university famously told him, “I don’t believe any Oriental student except the Japanese … can obtain a Ph.D. from a first-class university in America.”

But Jung does not just focus on how Koreans arrived; he also looks at the political history of people in this area. He writes about how and why various organizations formed, including the politically progressive Saghgnoksoo, which has welcomed those who may not have a home in many Korean American churches—such as LGBT Koreans.

The historian deliberately makes a point of including those Korean Americans that may feel marginalized within the greater community. “One of the things we try to highlight in the book is Korean Americans who may not appear to be typical Korean Americans—multiracial Korean Americans, Korean adoptees…,” he said. “So I think, for that reason alone, you’ll get a different sense of who and what Korean Americans are.”

Jung signs copies of the book at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum.

Jung signs copies of the book at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum.

At the June 4 book launch, Jung tested the audience of about 75 on their knowledge of the regional Korean American community. Some of the “pop quizzes” answers—like the fact some 20 percent of Koreans in Washington state are adoptees, or a quarter are hapa—elicited loud “oohs” and “aahs.”

“We’re a very fast growing population—one of the fastest [growing] ethnic groups across the United States, but especially Washington state—and we are incredibly heterogeneous,” he said. “We are not what we appear to be. And we have built many organizations, political groups and world views shaped by those differences.”

In a way, Han in the Upper Left has been an effort in the making since 1985, the year of the Korean American Historical Society’s founding. The organization always had the intention of putting forward comprehensive works on Korean American history—and for years it has with journals and oral histories. A book, however, began to feel like a pipe dream, as original editors and members succumbed to illness and age. Robert H. Kim, a now-retired professor from Western Washington University, remembers teaching in the 1960s and ’70s, when there was little material available outside of dry demographic studies. Teaching his students about Korean Americans was a challenge simply because there wasn’t any real information on who this burgeoning community was.

Kim started what would become Han in the Upper Left about seven years ago, but had to step away from the project for health reasons. While the final book isn’t near “the magnum opus” the team had originally envisioned, he said he was happy to see it finally in print.

“From now on the second, third and fourth generation of Asian Americans should try to keep our memories alive,” Kim said. “I strongly believe community without memory is no community. We are what we are because of our memories.”

For Jung, the book’s publication is not only a “relief,” but also gratifying in that it gives the scholar a chance to relay that “political message” he referenced earlier. It’s a message that’s clearly stated at the book’s conclusion: “We cannot ignore, dismiss or malign the most vulnerable among us—the poor, queer and transgender youth, battered women, undocumented workers. Attuned to our differences, to enduring hierarchies all around us, we can perhaps begin to imagine identities and communities that grapple with our varied and fractured histories to move to a more just world,” Jung writes. “These aspirations are the ongoing legacies and contradictions of han. They should shape interpretations of our past and visions of our struggles ahead, in the upper left and beyond.”

See Also

Korean Australians Thriving Down Under

Euny Hong Explores How Korea Got So ‘Cool’ in New Book

___

This article was published in the June/July 2015 issue of KoreAm. Subscribetoday! To purchase a single issue copy of the June/July issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only. Expect delivery in 5-7 business days).