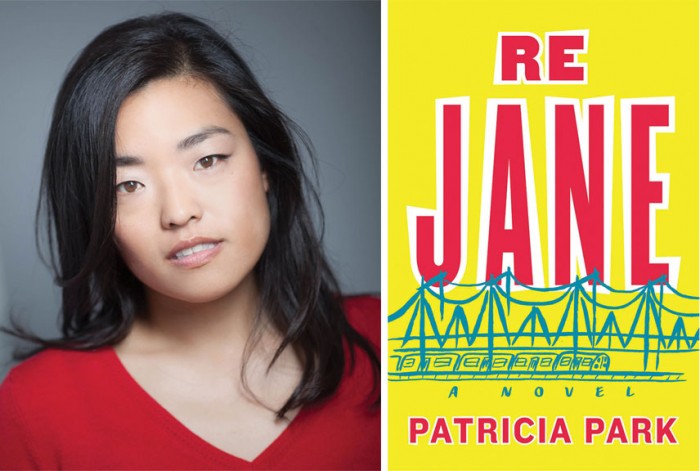

Pictured above is Korean American author Patricia Park with the cover of her debut novel, Re Jane. (Headshot by Allana Taranto)

by REERA YOO | @reeraboo

editor@charactermedia.com

When Korean American novelist Patricia Park first read Charlotte Brontë’s Victorian novel Jane Eyre at the age of 12, she was struck by how the titular heroine was scorned by society and her relatives solely because of her orphan status. “Orphan” was a word Park often heard her mother throw around whenever she misbehaved as a child.

“My mother used to say to me in her limited English, ‘You act like an orphan!’ This never made sense to me,” Park, 34, tells KoreAm via email. “How do you act like an orphan? You either are one or you aren’t.”

After reading Brontë’s 19th-century tale, Park realized that her mother’s generation of Koreans—those who grew up during the Korean War—perceived orphans as outcasts with questionable lineage, morals and manners. To “act like an orphan,” Park realized, meant you behaved in a shameful way that proved to others you didn’t receive a “good family education.”

“My mind drew the link between the Victorian construct of the orphan and the Korean post-war one, and Re Jane was born,” Park says.

Korean girl carries her brother on her back at Haengju (left). Young Jane Eyre confronts her aunt.

Korean girl carries her brother on her back at Haengju (left). Young Jane Eyre confronts her aunt.

Released in hardcover in May, Park’s debut novel is a modern retelling of Brontë’s classic tale, only set in New York’s sprawling outer boroughs and South Korea in the early aughts. Jane Re is a half-Korean, half-Caucasian recent college graduate who, since childhood, has lived with her strict uncle and his family in Flushing, a neighborhood Jane describes as “all Korean, all the time.”

When Jane’s cushy job offer at a finance firm is rescinded due to the dot-com crash, she takes a job as an au pair for a progressive Brooklyn couple with an adopted Chinese daughter. It’s a desperate effort to escape working at her uncle’s bodega and Flushing’s crushing weight of nunchi—an untranslatable Korean “ability to read the situation and anticipate how you’re expected to behave.” (Jane’s geeky friend Eunice likens it to “The Eye of Sauron” from The Lord of the Rings: “an all-knowing stink eye that monitored your every social misstep.”)

Soon, Jane finds herself inducted into a world of organic food and scholarly feminist books by her employer, Beth Mazer, an eccentric women’s studies professor with an attic office, and begins an affair with Beth’s husband, Ed Farley.

Their blossoming romance, however, falls apart when a death in Jane’s family occurs and she travels to her birth country of South Korea. After reconnecting with family in Seoul, the young heroine decides to extend her visit indefinitely after the 9/11 attacks and tries to adapt to modern-day Korean culture. As Jane shuttles from Queens to Brooklyn to Seoul and back, she struggles to carve out an identity for herself, finding that she’s neither Korean nor white enough to neatly fit into the roles each location assigns her.

In one chapter, Jane expresses this frustration by saying, “To be almost seemed to be worse than being not at all.” While the Korean mentality towards honhyol, or mixed-race Koreans, has changed over the past 15 years, Park notes that Jane grew up during the ’80s, a period when Korean society still strongly valued ethnic homogeneity. For Jane, who is told she was conceived from a onenight stand with an American G.I., her “mother’s shame” is manifest on her face.

“Jane, as a biracial Korean, is marginalized within an already marginalized community; she can feel the eyes of Flushing lingering a few beats too long on her face. She basically feels like a freak,” Parks says. “For me, Jane’s marginalized status parallels that of Jane Eyre, who is relegated to the outskirts of society.”

An 1847 illustration of Jane Eyre and Mr. Rochester.

An 1847 illustration of Jane Eyre and Mr. Rochester.

One of the greatest challenges Park faced in modernizing the Brontë classic was making Jane Re more active than her Victorian counterpart. Although Jane Eyre is celebrated as a feminist icon who was independent and strong in spirit, Park says that the original Jane is still a “product of her times.”

“There’s a joke that Victorian female characters sat around waiting for one of four fates: marriage, inheritance, immigration or death,” the novelist says. “Early drafts of Re Jane hewed closer to Jane Eyre, as well as conventions of the 19th-century novel. With each draft, I had to work to make Jane more active than simply reactionary.”

Born and raised in Flushing, Park began writing Re Jane nearly a decade ago during an MFA fiction writing program at Boston University. After graduating, Park received a Fulbright grant to Seoul to research Re Jane. Like her protagonist, Park arrived in South Korea with a rather naive view of the country, as she was weaned on her Korean Argentine immigrant parents’ stories of “kind-hearted village folks who would drink rice wine in the town square.”

One look at cosmopolitan Seoul shattered that mental picture, and Park found that the country had advanced exponentially since the Korean War—not just economically but also linguistically.

“The Koreans found me rather amusing. I sounded like a 65-year-old fuddy-duddy with a Southern twang. I peddled words like ‘outhouse’ and ‘apothecary,’” Park recalls, adding she would also employ outdated terms used during the Japanese occupation of Korea.

In Re Jane, Park addresses the conundrum of reverse immigration that gyopo, or Koreans raised overseas, face when they return to the “motherland”: expecting to be welcomed with open arms, only to find that they do not belong.

One comical but raw scene in the novel poignantly presents this cultural disconnect through Sang, Jane’s uncle who fled North Korea during the war and later immigrated to Flushing. Sang visits his family in Gangnam for the first time in 30 years and struggles to learn how to use a talking digital toilet; in the Korea he left behind, the “night-soil man” still made rounds to each outhouse. When Sang complains about the toilet’s complicated mechanics, his older brother humiliates him by saying, “You’ve been out of our country for too long.”

“Sang’s version of Korea, much like my parents’, is frozen in time and sadly no longer exists, save for a stretch of Queens,” Park says. “Sang’s experience going back to Korea is a bit like ‘no country for old men.’”

The 7 train heading to Flushing, Queens. (Screenshot captured on Youtube/timosha21)

The 7 train heading to Flushing, Queens. (Screenshot captured on Youtube/timosha21)

For Jane, who has always felt like a foreigner in Queens and Brooklyn, Korea is a mysterious country that holds answers about her past and her mother and father. It’s a place Jane could potentially call home—except, when she arrives in Seoul, she finds herself even more of a foreigner than before, as she is unable to fluently speak Korean or immerse herself completely into Korean social customs.

It’s only when Jane returns to Queens that she loses the nunchi that has always dictated her behavior and starts deciding who and where she wants to be without accommodating other people’s opinions of her.

As New York City moves past the uncertainty of post-9/11 life and the gentrification of Brooklyn and Queens unfolds, Jane also transforms from a meek and impressionable girl with a deep sense of loneliness into an independent woman who makes her own way in the modern world.

In the book’s epilogue, Jane seems to find peace with her struggles as a young twentysomething and mixed Korean American. Riding the 7 train to Flushing, she reflects, “I’ve grown familiar with its herky-jerkiness, learning to accept its particular rhythms instead of fighting against them—or running away. I’ve begun to feel a comfort in its clumsy rocking.”

___

This article was published in the June/July 2015 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the June/July issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only. Expect delivery in 5-7 business days).