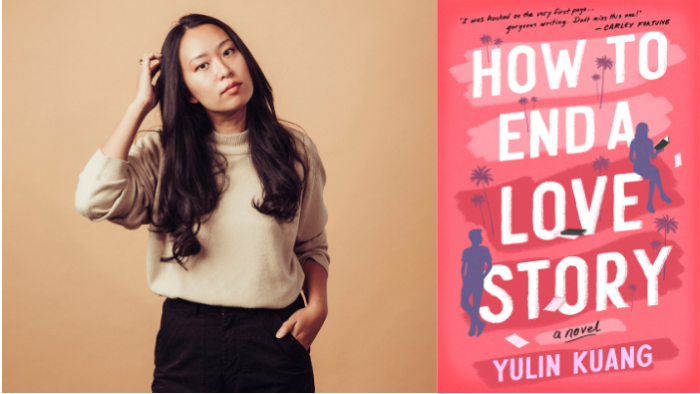

Photo by Mark Edward Harris

The Performer

Yebin Mok competed alongside such famous figure skaters as Michelle Kwan and Sarah Hughes, striving for medals and that big Olympic dream. But that striving soon turned into an obsession with perfection that sent the young skater on a path toward self-destruction. It would take leaving the sport—which literally was her life—for her to find her love for it.

by CHELSEA HAWKINS

After a decade of hard work, Yebin Mok was on the cusp of a breakthrough. She had just completed the skate of her life at the 2003 State Farm U.S. Championships. Performing to “The Swan,” the lithe 18-year-old nailed all her jumps—with commentator Peggy Fleming even gushing over her “beautiful toe-loop”—and closed her program with an effortless layback spin. By the end of her short program, Mok, the final skater on the ice, was met with a standing ovation from the appreciative crowd. If she medaled here, she would be one step closer to the Olympics, every competitive skater’s dream.

Sitting in the kiss-and-cry area with her coaches, she listened to her scores and then let out a delighted squeal when she learned that she had moved into fifth place out of 21 skaters, trailing such media darlings as Michelle Kwan, Sasha Cohen and Sarah Hughes, who topped the leader board.

With such formidable opponents, the odds were stacked against her, but Mok had the makings to be a medalist.

She had won the 1997 and 1998 Junior Olympics at the juvenile and intermediate levels, often outpacing older, more experienced competitors. By 1999 she was competing at the Junior Nationals, coming in a respectable fifth, and from 1999 to 2003, she was medaling in international junior skating competitions.

She had been training tirelessly, supplementing on-ice time with ballet, gymnastics, personal training off the ice, and working with nutritionists. She had bypassed traditional education, thereby sacrificing the typical teenage experience, instead choosing to be home-schooled—all in the name of the sport.

Success in skating is a medal, it’s the Olympics, and the 2003 U.S. Championships was Mok’s launching pad.

But, when it was time for her long program, Mok, donning a bright red skating dress, faltered on technical elements, first opening up on a triple jump, and then on another one. She had appeared to lose focus. She would finish sixth. No medal. No Olympics.

Yebin Mok (back), with other skaters at the 2002 Trigslav Trophy (Kim Yuna is pictured in the hanbok on the left, and Evan Lysacek is on the right). Photo courtesy of Yebin Mok.

Yebin Mok (back), with other skaters at the 2002 Trigslav Trophy (Kim Yuna is pictured in the hanbok on the left, and Evan Lysacek is on the right). Photo courtesy of Yebin Mok.

“That was my one shining moment… it was the best skate of my life,” said Mok, now 28, nearly a decade after her nearly flawless short program.

But it wasn’t enough.

“At that moment, that’s when it clicked for me—that was not the kind of skating I wanted to be doing,” she said. “I didn’t want to sacrifice my sweat, blood and tears every freakin’ day for these nine judges.”

But actually, her sacrifice went far beyond that.

While skating competitively — even during the 2003 U.S. Championships — Mok struggled silently with eating disorders, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. That pattern of self-destruction ultimately is what compelled her to walk away from skating in 2005.

“I needed to get out of it,” she said. “I needed to stop mentally torturing myself, and skating was doing that to me.”

***

It was in 1994, in Culver City, Calif., where a 9-year-old Mok first laced up a pair of skates. She fell in love instantly with the sport, and her parents signed her up for lessons.

Originally from South Korea, Mok had immigrated to the United States with her family when she was 7 years old. The move to the U.S. was meant to be temporary, after the company Mok’s father worked for had transferred him to a Los Angeles office, but the family decided to make the transition permanent. Although the decision was so they all could have a better life in the States, the young Mok thought her skating career heavily influenced her parents’ decision to stay in the U.S., and she felt even more pressure to make them proud.

Indeed, she did. It became clear she was a talented skater, and Mok progressed quickly through the ranks, nailing jumps and gliding through footwork. As a junior-level skater, Mok walked away with trophies and medals. “I kept progressing really fast and doing really well in competition from the get-go,” she recalled. “It was unexpected, but it was a full charge of getting to the top, top, top, and at that point, you can only go higher.”

But, as she moved up in the ranks, competing at a senior-ladies level, the pressure mounted. In 2000 she began to work with Frank Carroll, the same coach as Michelle Kwan. Around that time, she was also racked by a series of injuries. In the summer of 1998, she suffered a stress fracture and was off the ice for three months. Two years later, it was a pinched nerve in her back that aggravated her, and then in 2003, following the U.S. Championships, a stress fracture in her lower back kept her from training for five months. This was followed by ganglion cysts on her ankles, requiring surgery for removal, and another four months off the ice.

While dealing with these injuries, Mok said she began to “get mentally screwed up.

“I was literally no one without skating,” she said.

Photo courtesy Yebin Mok

Unable to follow her normal training regimen, Mok said she found other ways to force her body to conform to her expectations, altering her eating habits dangerously. It gave her a sense of control.

“It’s not uncommon for my skating peers to do that [too],” Mok noted. “After I would eat, I’d throw up. Or, I would just drive from fast food to fast food to fast food just to fill the void, and then feel bad about it.”

She became wracked with guilt, but it was guilt borne out of a desire to be perfect.

As an athlete, her body was her sole instrument. If she wasn’t good enough, it could only mean something was wrong with her body.

“It … creeps up in your everyday life, from how you’re eating, to how you’re not doing everything possible to achieve that goal of winning … [and] going to the Olympics,” she said. “I would feel bad if I didn’t sleep in the right position because that was bad jumping position. Just psycho, just OCD.”

When she finally returned to the ice after recovering from her injuries, she grew more frustrated.

“My technique was not coming in a timely manner, like I wanted it to,” Mok said. “When I didn’t practice well or didn’t land a jump like I wanted to, I’d get really depressed and go into food binge/purgeepisodes, and punish myself.’”

After she had ankle surgery, things worsened. Figure skating was no longer something she enjoyed; it was a job, an all-consuming burden. At one point, Mok was even counting the amount of breaths she took before she slept.

“I just wanted to please and satisfy everyone and change myself. Change my hair, change my make-up, change my costume, change my program. I needed [to do] more, more, more,” she said. “I just completely lost myself. I got further away from who I was.”

Looking back, Mok realizes she was chasing something she never really wanted.

“My idea of success when I was little was the Olympics because that’s what everyone goes for in skating, but I wish it was different,” Mok said. “My calling was to bring that magical performance to the ice—that’s why I was into skating.”

But even if she subconsciously didn’t want the Olympic gold, she was still stuck on a one-way path toward striving for it. All roads led to the rink, to rehearsals, and, ideally, to the podium.

Mok’s life became a competition. She recalled talking with other figure skaters about the number of calories she took in and the amount of time she devoted to working out. Each girl wanted to outdo the other.

Mok had whittled down her daily caloric intake to a dangerously low 710. To put that in perspective, it is recommended that healthy young women take in around 2,000 calories a day. A young, extremely athletic woman could easily take in more than that because the more active you are, the more calories you burn.

Mok wasn’t even taking in enough to live a healthy life.

“I started to binge, binge-purge, and then I just looked horrible. I felt horrible … and obviously in that state, how could you perform? How could you exercise? [How can you] connect your mind and body to do everything it’s supposed to do when everything is off?”

Photo by Michael Higgins

Mok lowers her voice and peers downward before explaining “the pivotal

moment” in her skating career in 2005. One day, she drank an excessive amount of alcohol, desperate to force herself to throw up. Finding her at home drunk, her parents were shocked. But she told them that she was only trying to force herself to vomit and why.

“[My parents] said ‘Oh my god, we had no idea! Just quit skating! This is not how you want to live your life, this is so wrong.’ So I think that gave me the courage to quit,” Mok said. “I couldn’t be normal in that environment. [My parents] were just like, ‘We don’t want you to hurt yourself, we love you,we want you to be OK.’”

***

Sitting at a Santa Monica café, the woman in front of me has a lightness about her.

Wearing a black athletic jacket, fitted leggings and sneakers, she looks like she just left a training session. Her hair is tied back, save for a few flyaway strands, and her face is fresh and youthful. In this moment, she’s projecting health and optimism. When our cups of frothy green tea are brought out, she smiles at the swan and bear shapes in the foam of our drinks and comments on the sweetness, before returning to our conversation.

“[Quitting skating] felt like a weight was lifted off of my shoulders,” said Mok. “It felt really good in my heart to do something that was right for myself, which was scary because skating was the only thing that I knew. But it was fresh—it was a fresh start.”

After leaving the ice in 2005, Mok tried everything. She attended a community college, which would be her first time in a regular school environment in seven years. She worked as a hostess and an ice cream scooper, and dabbled in drawing, writing, ballroom dancing and Bikram yoga.

“I just wanted to know, who am I in the world without skating?” she said. “I kind of pushed myself into every corner that I could [in order] to see who am I? What am I? What do I want in life?”

She laughs about it now, but at the time she left skating, Mok said she didn’t even want to “hear the s-word.”

Yet, after only a year away from the ice, she felt an itch to get back. After an unsuccessful attempted comeback during the 2006-2007 season, she bid a final farewell to competitive skating.

But that would turn out not to be a farewell to skating itself.

In the spring of 2008, Mok applied to work for her first ice show, Holiday on Ice. No longer vying for a medal, she felt like she could focus on what it was that drew her to figure skating in the first place.

“I wasn’t into all these jumps,” she said. “I was just so mesmerized by beautiful skating, and I felt like I was in another world. And that’s what’s so special about skating or art in general. Art has the ability to do that, and that’s why I wanted to skate.”

For the past four years, she’s starred in ice shows in Europe and Canada. She has even performed for the president of Lebanon.

Making the transition from competition to performance skating proved challenging. Mok admitted she would still get frustrated when she didn’t land a jump or perfectly execute an element.

“As an amateur, you think only about you, your jumps, your technique, and getting that right for that one four-minute program. But in professional skating, there is you, but there are 10,000 people watching you, that came to see you, night after night 10 shows a week.”

“It is and it is not about the jumps. First is performance,” Mok continued. “Jumps are a part of choreography. Elements become fused into choreography and music, making it even more beautiful, freer and more effortless. That is how a great performance is made, and that is something that I had to consciously learn, change and grow from because I was still stuck in the idea of competitive skating.” That’s a mindset she would like to see other young skaters abandon.

Mok, who teaches skating and is also training to be a yoga instructor, still has the diaries she kept as a young skater. “When I look back at my diaries, it’s just,” she began, then paused, searching for the right words. “Depressing,” she continued. “I can’t believe I was so mean to myself. If I could go back to that girl, I’d say, ‘Ease up. It’s not the end of the world, you know?’”

Mok urges young skaters to consider the world outside of competition, and to consider skating solely for the love of it. “As a performer, I simply invite people to come to the venue, to come into what is ‘my world,’ and my goal is to simply touch and inspire people through performances.”

Her long-term goal is to open a training facility for figure skaters. But unlike training facilities now, it would encourage skaters to pursue all their options, as performers and competitors.

When she was a competitive figure skater, when she was working toward the Olympics and a medal she never even wanted, figure skating was “do-or- die”—it was about determination, willpower and success at any cost. But what is figure skating to her now?

“It’s love,” Mok said. “Now it’s just pure love, expanding and forgiving.”

This article was published in the August 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the August issue, click below.