by RUTH KIM

Juniper Song is back, and Death has come knocking on her door again. The young Korean American sleuth can’t seem to escape the hooded, scythe-wielding figure who’s constantly been lurking in the shadows of her life, from the untimely passing of her unremembered father to the fresh-blooded suicide—or was it murder?—of an A-list celebrity at The Roosevelt Hotel.

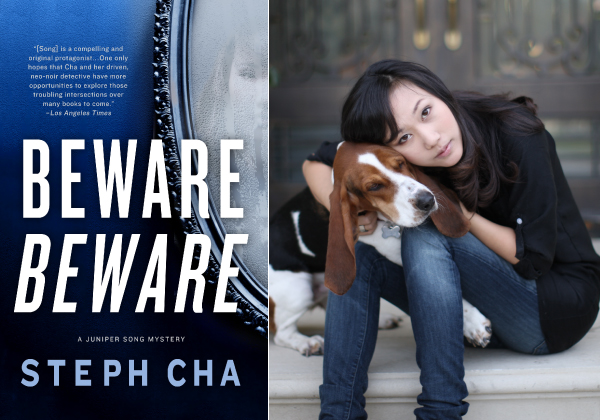

The latter is the latest case to wind up on Song’s lap in author Steph Cha’s new novel, Beware, Beware, released earlier this year. Beware, Beware marks the anticipated sequel to Cha’s debut, Follow Her Home, a page-turner that impressed a well-read noir audience with its genre-defying protagonist. Bringing to the fore an independent, Asian female lead, Cha navigates the reader through the streets of the unsavory underbelly of present-day Los Angeles—a map that eerily reads much too familiar.

When a young Daphne Freamon from New York calls L.A.-based investigation firm Lindley & Flores and asks for a tail on her boyfriend, Jamie Landon, Song picks up what she thinks is just another “low-glamour” assignment. Sleuthing around L.A., the young detective trails Jamie, who works for A-list movie star Joe Tilley, from Sunset Boulevard to the hills of Los Feliz for weeks. But the case unexpectedly escalates when the famous celebrity winds up dead by suspected suicide in the penthouse bathtub of The Roosevelt Hotel.

“There was nothing there, no report of life, just cold skin going waxy with its own irrelevance,” says Song, as she checks for a pulse on Tilley’s body. “My fingers smeared with a film of death, I lowered my palm to the surface of the water. No heat rose, and with one dread-filled fingertip, I tested the bath. The surface broke, and the bloodied water wrapped around my finger. The temperature matched the room, and all at once I felt that the room was very cold … A deep gash ran from his wrist to an inch above his elbow. I stared at it with nausea and somewhere, a tingle of fascination.”

And with just one turn of the page, Song finds herself neck-deep in yet another unsettling case, which spans well over 200 pages of excessive chain-smoking and far too many emptied glasses. But more than your typical mystery novel, Beware, Beware exhibits Cha’s talent for creating an original and compelling character that Korean American readers, and audiences in general, aren’t used to meeting.

Aside from being an aspiring private detective, Song is a Korean American and native Angeleno who knows her city like a mother knows her child:

Our office was only a half-mile from T & J Collision Center, across a representative chunk of Koreatown, crammed tall with redolent restaurants and low-rent office space. Signposts advertised in tacky block letters, many of them Korean, another large chunk of them in Spanish. When angry white Americans worried about losing control of their country, Koreatown was the wrecked city of their nightmares. Ancient Koreans lived in sallow, stucco apartments, within short bus rides of their Korean markets, doctors, and video stores. My own grandparents had spent their last years in a one-bedroom on New Hampshire, dying without five words of English between them. The Mexicans working in Koreatown didn’t bother with English either, but they could rattle off Korean with the soft round tones of native speakers.

Cha’s raw and accurate assessment of present-day L.A. Koreatown establishes a distinct rapport with her Korean American audience. With Korean words sprinkled throughout the novel, Beware, Beware displays the nuanced conflicts Korean Americans face growing up in a Korean community in America, from the importance of unquestioningly respecting your elders to the way Asian women are still subjected to the idea of Orientalization, reduced to the archetype of the quiet and docile woman.

Hardboiled and with what some would call reckless audacity, Song shatters such stereotypes, boldly overstaying her welcome in palpably strained situations and proving her competence as a female private eye. But it’s often been this audacious behavior that has gotten Song, and her loved ones, into trouble in the past.

Haunted by the ghosts of her mistakes, she seems to be attempting to right her wrongs, operating on an innate moral compass that guides her on a virtuous, but often dangerous path. Giving a nod to detective fiction writer Raymond Chandler, Cha endows Song with the aspiration to be like her literary idol, Philip Marlowe, the fictional P.I. who sleuthed around 1950s Los Angeles in Chandler’s novels.

“Maybe it was the Marlowe in me,” says Song, wistfully. “Weary as he was, the man had a stubborn belief in people, that they could be decent, worth helping, worth saving. He suffered a lot for that belief.”

Such faith in the inherent goodness of humanity brings Song her fair share of grief, and she certainly suffers the consequences. But it’s precisely these character flaws that make this novel’s protagonist a fascinating femme fatale in her own right.

Images courtesy of Steph Cha