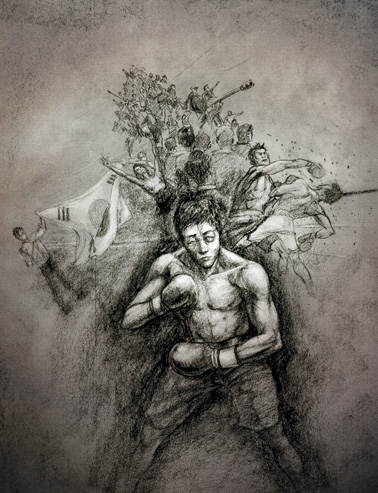

Still the Champ

Thirty years ago, boxer Kim Duk-koo met his untimely demise during a championship fight in Las Vegas. A writer reflects on what he meant to Koreans and Korean Americans, then and now.

by STEVE HAN

illustration by INKI CHO

In 1982, American boxer Ray Mancini sent a fatal straight right into South Korean Kim Duk-koo’s face in the 14th round of the World Boxing Association lightweight title match outside Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas. For wincing Korean audiences, the blow struck particularly close to home.

Less than three decades after the Korean War ended, South Korea was still a struggling nation. The country’s per capita annual income barely eclipsed $3,000 at the time, according to the World Bank’s data. President Park Jung-hee’s dictatorship over the country had rapidly developed its industrial sectors, but left many workers and farmers poor while eschewing basic political freedoms. For many, daily living had not improved.

One thing South Korea did have was boxing. South Korea had become something of a boxingpowerhouse. Korean boxers found success disproportionate to the country’s size, and they fought with an all-or-nothing, do-or-die approach to the sweet science. Kim Ki-soo and Hong Soo-hwan found success in those decades after the war, paving the way for future Korean champs, and fueling the popularity of the sport in the country.

Not many homes owned television sets, so many went to local coffeehouses to sit around black-and-white televisions to watch their fellow countrymen fight for international recognition. Café owners arranged the seats in front of the TV, like a movie theater, according to Mi-ran Han, 51 (disclosure: my mother). Cigarette smoke and chatter filled the room in the tense minutes leading up to the fight, but once the match started, “the tensions were so high that no one smoked, drank coffee or ate,” she said. Kim Duk-koo’s fight was no exception, despite his having a bit less name recognition than some of his fellow pugilists.

“People didn’t really know who Kim Duk-koo was,” she said. “But once he was picked to fight a world champion, everything changed. A Korean fighting a foreigner in a title match? At the time, that was more than enough to get people to watch the fight.”

Athletes are often forged in privation, but Kim seems to have suffered even more than the average postwar South Korean. “Poverty is my teacher” were the words written in blood on a paper pinned on the wall of Kim’s room in Seoul, South Korea. Kim lost his father when he was only 2. He lived with his mother since then. His dream as a child was to have a bowl of hot rice.

When Kim turned 18, he moved to Seoul with no money. He was homeless, and subsisted on crackers and water while living under a bridge crossing the Han River. When the World Boxing Association named Kim the No. 1 contender for Mancini’s lightweight title, he was an outsider even in South Korea. Kim was determined to show the world that he was relevant. The story of his life would’ve turned into a Korean equivalent of Rocky had he won.

The bout was also a huge event for the Korean American community at a time when Korean immigrants were still a minor- ity of minorities in the United States. Kim fighting Mancini on live national television served as a platform to renew their identity.

“There were not many exciting events in the Korean American community 30 years ago, and the boxingmatch was one event that brought us together,” said Chong Ha, 74, a retired IT executive who watched the match stateside, on CBS.

Kim wasn’t much of a known quantity in the States either, but Mancini knew the fight would be tough. Mancini had grown up listening to his father, also a boxer, saying with pride how he’d “didn’t win ’em all … But I never took a step back.” Meanwhile, Lee Sang-bong, a training partner of Kim’s, recounted later how they’d agreed: “Stepping back was shameful.”

The fight turned into a savage battle. Mancini had the upper hand throughout, but Kim refused to go out, and roared back with punches to end each round. Mark Kriegel, the author of his re- cently publishedThe Good Son: The Life of Ray ‘Boom Boom’ Mancini, described the bout as a “stubborn accrual of brutalities.”

Thirteen rounds into it, Mancini charged off his stool and pounded Kim’s head with a right hook. He then connected a follow-up left hook to the rib and swung his right again to land another venomous shot on the head.

From that point on, Mancini launched over 60 unanswered shots. Kim absorbed them all, but somehow stayed on his feet to survive the onslaught. He then scraped, clawed and growled his way back into the fight by throwing rugged punches of his own.

“Look at him punch back!” CBS sportscaster Tim Ryan exclaimed.

In the following round, though, Mancini stepped right and caught Kim off guard with a left hook. Then, he unleashed a shat- tering straight right into Kim’s face and dropped him head first.

Kim wasted no time in crawling over to grab the ropes, pulling himself up to stand. The referee Richard Green waved his arms to end the fight. Kim’s last-minute effort to even stand was a miracle in itself. Ringside reporter Ralph Wiley of Sports Illustrated later described his effort as “one of the greatest physical feats” he had seen.

Kim collapsed to the floor and was carried out on a stretcher. Four days later, he died at the Desert Springs Hospital.

“We were in shock,” Ha recalled. “We all felt that we were knocked out and became speechless and helpless. We all had tears in our eyes. I don’t think anybody can understand how we felt at that moment.”

In Kim, many Koreans saw a reflection of their own paths from poverty to prominence. The boxer, marching through adversity with clenched fists under his gazing eyes, embodied the people who had faced Japanese rule, the Korean War and rapid industrialization within half a century. While the world sympathized with Kim, Koreans empathized with him. They understood exactly what Kim stood for when he pulled himself up to get back on his feet even as he was dying.

Enough was never enough. Stepping back just wasn’t an option.

“I believe Kim is someone who already experienced a feeling close to death considering the kind of life he has lived,” said Sung-hoon Cho, a longtime boxing fan residing in Seoul.

“That’s exactly why Kim couldn’t stop throwing punches until the moment he collapsed. Nothing scared him. When you’re so focused on achieving something, there comes a point where your body does what you’ve wanted it to do even when your mind is somewhere else.”

“Most people in Korea stopped watching boxing because they were that devastated,” said Han, my mother.

The Kims visit Duk-koo’s grave in South Korea. A still from The Good Son documentary, based on the book. Photo courtesy of Saint Sophia Productions.

Perhaps what truly makes Kim’s death tragic is that he died before seeing what his country would later become. Less than six years after his death, Seoul hosted the Summer Olympics—an event he promised his fiancée that he would attend with their soon-to-be born son before leaving for Las Vegas. The Olympics, of course, placed South Korea on the world stage, and the country’s rise has continued. South Korea now has the 12th largest economy in the world, according to the International Monetary Fund. And for a time, Kim embodied the fighting spirit that would help land South Korea in the top echelon of world’s developed countries.

Kim is remembered fondly in the country. “Everyone now remembers him as the ‘champion’ because of what he symbolized,” said Han. “Even the movie that came out later was titled Champion.”

Still, the country has left boxing behind. Fewer boxers come out of South Korea onto the world stage. Soccer and the more genteel sport of golf stoke nationalistic passions. The boxer no longer seems to represent the aspirational spirit of the modern South Korean.

Those closer to the participants couldn’t just leave it behind, though. Kim’s fiancée, Lee Young-mi, raised their son without his father. Kim’s mother, Sun-nyo, ended her own life four months after his death. Green, the fight’s referee, killed himself less than a year after.

Mancini, hailed as the local Italian American boy, went from hero to villain. He was never the same fighter. He suffered from serious depression, lost his title and eventually retired in 1993. Kids taunted his 8-year-old daughter at school, calling her father a murderer.

Kim Ji-wan, the boxer’s now-grown son, and a dental student in Seoul, told author Kriegel he wished his father had stepped back for his mother when it became clear he was fighting a losing battle against Mancini. The younger Kim watched the DVD of the fight only after he finally agreed with his mother to meet Mancini in Los Angeles in 2010. When the meeting occurred, Ji-wan confessed: “Now I can tell you that, when I saw the fight the first time, I felt some hatred to you.”

“[Now] I think it was not your fault,” he said. “You deserve. Maybe now your family will be more happy.”

Scars may last, but the healing doesn’t stop.

This article was published in the November 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the November issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only.)