By Kay Hwangbo

Photographs by Eric Sueyoshi

• • •

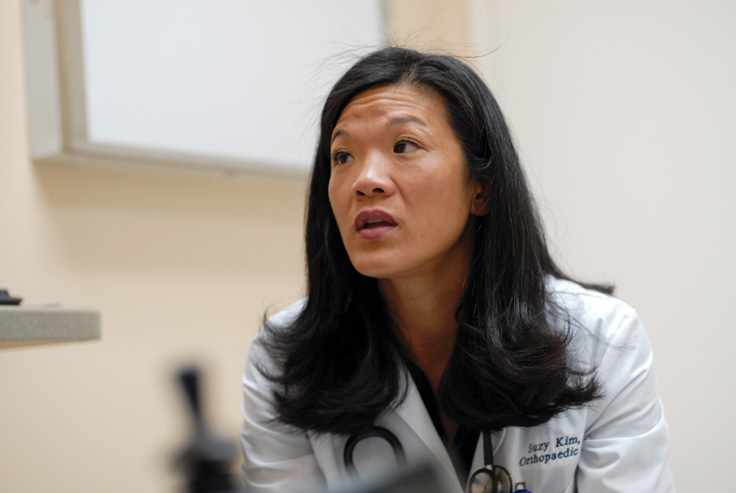

“Watch your head,” Suzy S. Kim says.

This reporter duck as she heaves the 12-pound body of her collapsible wheelchair into the backseat of her BMW convertible. Pulling on mirrored aviator sunglasses, the athletic doctor maneuvers her hand-controlled sports car out of the University of California, Irvine, campus.

The 36-year-old has just finished giving an interview about paralysis at the Reeve-Irvine Research Center. She is now taking us to the spinal cord injury clinic at the UC-Irvine Medical Center, where she treats patients who like her have some form of paralysis.

Kim is one of a handful of doctors who have a special certification in spinal cord injury medicine, who are themselves paralyzed. Only 500 doctors in the United States are board-certified in the subspecialty. Last May, she was hired to develop a comprehensive treatment program for paralyzed patients at the hospital. She also holds a joint appointment at Reeve-Irvine, where she advises scientists on maximizing the practical benefits of spinal cord injury research.

[ad#336]

Since the accident that paralyzed her 11 years ago, Kim has completed a triathlon, earned a humanitarian award, and according to friends, managed to see the funny side of difficult situations.

“For many people, you see somebody in a wheelchair, it’s uncomfortable for people,” said close friend Stephanie Goddard, 36. “With Suzy there’s none of that. She’s so disarming, with her humor and who she is.”

Kim’s thick black mascara gives her the appearance of a young Connie Chung. Her long hair curls upward in big curls. Her muscular arms give away her half-mile-a-week swimming habit. As we hurtle up Interstate-5, she says that scientific breakthroughs that might allow paralysis patients to walk again are important, but she also focuses on the now: improving the functionality of people with disabilities.

And because she’s been there, she has a deeper sensitivity to what her patients go through and what is important to them.

One of Kim’s patients, for example, wanted to switch from using adult diapers to a disposable catheter so that he could use public bathrooms. His urologist had brushed off the idea. But Kim developed a program for him to switch over because she instantly recognized that having the catheter would give him greater independence.

Debra Black, one of Kim’s patients at the Irvine hospital, said, “It’s just easier to talk to her, because she’s been there.”

“She’s the most persistent doctor I’ve ever had,” said Bob Yant, 57, of Newport Beach. One day, Yant — who is paralyzed from the chest down with limited use of his hands — noticed that he was having muscle spasms in his chest, abdomen and legs. He spent four months seeing top specialists in various fields, but all of them gave up after they determined that Yant’s problem wasn’t in their bailiwick. “Well Dr. Kim, she stuck with me through this whole thing.” Kim solved the mystery behind the spasms – they were caused by a bacterial infection, arising from a bladder stone. Yant’s stone was eliminated and the spasms subsided.

“Suzy has drive,” said Tricia Christen, Kim’s oldest friend. “She gets that from her mom, who was such a kind-hearted person. She did whatever it took to provide for her family.”

Bo Hyun Kim died 11 years ago after battling stomach cancer. She was diagnosed just a year before her daughter’s accident in 1997. Bo Hyun and Suzy’s father David D. Kim left Korea in 1976, believing their family would have a better future in the United States. David Kim operated a few dry cleaning businesses, first in New York and later in California, but ended up folding them. After other ventures, including an import-export business, did not pan out, Suzy’s mother became the sole provider for the family of five.

Bo Hyun Kim worked at a video store seven days a week. Later she got a job at an insurance company, where she eventually mastered English and earned the admiration of peers, according to Christen.

“My mother was always my role model, always persevering,” Suzy said.

• • •

[ad#336]

November 2, 1997. The day dawned chilly and clear at Laguna Beach. At John Wayne Airport in Santa Ana, 14 miles away, it was 63 degrees. But by 3 p.m. at the beach, it was 85 degrees.

Kim, then a medical student, and her boyfriend, Dave, also a med student, were body surfing and decided to catch their last wave of the day. The 5-foot-3 Kim was toned from a lifetime of playing sports: she had been named MVP in the Pacific Coast League for Varsity Tennis in 1990. She had even played soccer against Julie Foudy, U.S. women’s soccer legend, when they were both in high school.

Kim had body surfed — in which one uses one’s body as a surfboard to catch the wave — since she was in fourth grade. She grew up in Laguna Hills, six miles inland from Laguna Beach, where she went to school. She also did board surfing and boogie boarding. Kim and Christen used to walk to the beach after school with their boogie boards, catch some “tasty” waves, then take the bus home. “That’s where her love of the ocean came from,” said Christen, a nurse who lives in Mission Viejo.

At the main part of Laguna Beach, in front of the basketball courts, there is a nasty undertow that has whipsawed many an unsuspecting swimmer. As the late-afternoon sun glimmered on the water, Kim saw the wave that she thought would be her ride back to the beach. The wave caught her body, then slammed her, head-first, into a submerged sandbar.

“It literally felt like 10 guys picked me up and threw me down,” Kim said. The wave had smashed the top of her head squarely into the shoal, breaking Kim’s neck at its base. Kim lay on the ocean floor, unable to move, thinking only that her foot was caught on something. She held her breath for interminable minutes. Eventually, Kim’s body was carried to shallower waters. She lifted her head out of the water, attracting Dave’s attention. He and a passerby surfer carefully carried Kim onto the sand. (Kim declined to give Dave’s last name for personal reasons.)

A lifeguard asked Kim if she could move her hands or wiggle her toes. He touched her legs, arms and trunk, and asked if she could feel anything. She had some faint feeling, but couldn’t move anything. “That’s when I started panicking and hyperventilating,” Kim recalled. The lifeguard, realizing that Kim had a spinal cord injury, called for a helicopter to take her to Mission Hospital, a medium-level facility for treating trauma cases.

“I’m very thankful that the lifeguard made the right diagnosis,” Kim said. The doctor frequently uses words like “lucky” to describe herself. Kim became what’s known as a high-functioning quadriplegic: Below her chest, she had sensation, but no movement. She could move her wrists some, but not her hands or fingers. She also couldn’t control her trunk muscles below her chest. At first, she couldn’t even sit up: “It was like I was on top of a column of Jell-O.”

After reconstructive surgery, Kim asked her neurosurgeon, “Am I going to walk again?”

“He said, ‘It’s very unlikely, but we don’t know for sure,” Kim recalled. “We have to let time take its course.’ I was in disbelief. I really honed in on the fact that the doctor had said ‘we’re not sure.’” In the meantime, Kim’s mother was in the end stages of her battle with cancer. Two-and-a-half weeks later, she died.

Kim said she cried every day for two years after that terrible time. Her tight-knit family, including her father, older sister Angel Honda and younger brother David K. Kim, supported her emotionally, as she completed six weeks of residential rehab at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in Downey, California. For the next nine months, she labored in out-patient rehab to get greater control over her “core” and hands. After seeing the work that her doctors, physical therapists and occupational therapists did, she decided to become a doctor of physical medicine and rehabilitation.

[ad#336]

“I think for me, it was, ‘There’s gotta be more,’” reflected Kim. “The doctor who [was] supposed to be guiding my rehab, not to dump on him, but I was thinking, ‘This could be better.’ Especially for young people who are young and healthy,” who may want to do more than “maintenance” physical therapy.

In September 1998, only 10 months after her debilitating accident, she re-entered medical school at the University of Southern California. Kim credits USC for accommodating her physical limitations, allowing her, for example, to train in fields that are less physically rigorous, such as psychiatry, first. Eventually, she would regain 90 percent of her hand function.

In July 2004, Kim finished medical school and received additional training in rehabilitation medicine at the prestigious Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. She also trained at Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, which won an award for its rehabilitation program while she was there. Officials had put up a big banner touting the hospital across its facade. One day, when Kim was crossing the street in front of the hospital, her wheelchair flew out of control at the curb, which did not have a curb cut. She fell out of her chair. Lying in the street, she began to curse. Then she noticed the sign: “#1 in Rehab.” Kim laughed and laughed.

“She’s always been that way,” said Kim’s friend Stephanie Goddard, who related the story. “She’s always been able to laugh at herself no matter what the situation. She’s always maintained that through the most difficult times.”

The physician went on to treat paralyzed patients at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, and in 2007, received board certification in rehabilitation medicine, as well as in her narrower specialty of spinal cord injury medicine.

“One of the things that makes my job meaningful, is tackling cultural stereotypes about people in wheelchairs,” said Kim, an Irvine resident. “I like working with minority patients and families so that they can really understand that, even with an injury, they can still have a productive life.”

While she was working at Santa Clara Valley, it was considered to be one of a dozen model facilities for the treatment of spinal cord patients in the United States. Kim, now as the medical director of the spinal cord clinic at UC-Irvine hospital, is trying to develop a similar world-class facility in Irvine. “Her training and background are impeccable,” said Oswald Steward, director of the Reeve-Irvine Research Center, where Kim is the Science Liaison. “She is also amazingly articulate, very persuasive and very interactive with people.”

Kim’s paralysis is obviously not the first thing those who know her see. Instead, she’s that colleague who tears up the freeways in her silver sportscar. Or the friend who’s a secret fan of Britney Spears.

She’s the woman peers, patients and loved ones revere.

Christen recalled the impressive showing of her, Kim and another friend, Jenny Severson, at the Long Beach Triathlon last September. At the beginning of the race, Christen and Severson carried the doctor from the starting point to the ocean. Wearing flotation devices on her ankles, Kim then stroked powerfully alongside her two teammates. Although the “carry” had slowed them down, once they were in the water, the trio passed about 20 able-bodied people, including young men. Kim navigated the cycling and running portions of the race with a hand-powered bicycle.

“We were able to do it because she’s so dedicated,” Christen said. “She’s superhuman. I really think she is.”