By Bao Phi

“Star… board,” the Korean gangster says haltingly on the beach to his wife. And then come the tears. His wife has just handed him a small book of English words, a text that will help him communicate with those he’s joining on the rescue raft. She had once secretly learned English so that she could leave him. Now, after a plane crash that has left them stranded with strangers on an island, she hopes her secret will save him. Their relationship after the crash has been even rockier than it was back in Korea. But on the island, where they now barely survive as castaways, they are slowly rediscovering their love for one another. As he gets on the raft to search for help, they embrace and share a passionate kiss. And for the first time, the American public is witness to a primetime Asian couple in love.

It all started in 2004. The series, which followed a group of survivors stranded on a mystifying island after a plane crash, was intriguing from Day 1; it had cast two Korean–speaking characters and employed the use of English subtitles as they conversed.

Initially, I had dismissed the show. But some very impassioned peers kept lauding the fantastic premise, the intriguing Iraqi character and, above all, the nuanced Korean characters.

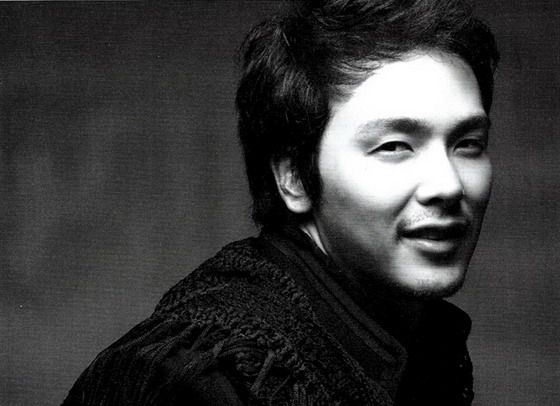

Sun-Hwa Paik, played by Yunjin Kim (famous for her role as a spy in the South Korean blockbuster Shiri), is a complicated woman. The daughter of a wealthy criminal, she defies her familial expectations when she falls in love with the poor fisherman, Jin-Soo Kwon (Daniel Dae Kim). In order to marry Sun, Jin must work for Sun’s mafia father as hired muscle, administering beat-downs at his command. As he becomes increasingly detached and volatile, Sun learns English so she can escape life in Korea, and has an affair.

If it sounds like the show’s writers relied on the same tired stereotypes, it’s because they did. At least, at first.

When it comes to representation in film and television, if Asian Americans are portrayed at all, it’s usually as a martial arts villain/punching dummy for a Caucasian hero, or a female victim clinging to a white knight. Pun intended. Arabs are either terrorists, or the brown people who die to teach you a lesson about intolerance.

Truthfully, the first few episodes of Lost didn’t help the cause. Here was a patriarchal, abusive and domineering Korean husband and his docile Korean wife, two characters seemingly tailor-made for that type of condescending, patronizing and self-congratulatory first-world liberation story that seems so popular in Hollywood. The early episodes made me cringe, and still do: Jin slapping Sun’s hand, Sun strutting slo-mo in a bathing suit as if liberated from the Korean cloak of oppression.

And then there was the show’s embarrassingly sensationalized depiction of the antagonism between Jin and one of the few black characters on the show. In an early episode, after Jin violently attacks Michael (Harold Perrineau), Michael tells his son that Koreans do not like black people. Of course, the Asians get no say in this matter.

But by the final season, Lost had rewarded loyal viewers with two beautifully flawed Asian characters who grew and transformed, and their relationship was easily the most compelling of the many featured on the show. Their scenes sent chills: Sun’s tear-streaked face when discovering that her baby was, indeed, Jin’s; Sun screaming in agony from a chopper as she witnesses Jin engulfed in an explosion.

The many times that Jin and Sun were separated during the series gained them a tragic star-crossed lovers vibe; it was as if fate couldn’t allow the two of them to be together. But those of us who were Jin and Sun fans felt that their relationship, despite adversity, was actually the stronger for it. Sun and Jin’s love, despite the circumstances, felt soulful and endearing compared to the blown affairs and triangles of their fellow islanders—many of whom just couldn’t get it right despite their proximity. And when they finally came back together at the end of this year’s final season, only to die in each other’s arms a couple of episodes later, those of us who loved those characters drowned with them.

Sure, the show had its share of disappointments. Two Arab characters fall in love—yet instead, Sayid hooks up with a spoiled blonde in the afterlife? Get outta here. Jin and Sun speak in English during their last moments together? Come on.

But what sounds so simple—the love between the two Asians—makes you wonder why we don’t see it more often on American television. For Asian Americans, a pop culture representation of two Asians kissing is an urban legend akin to Bigfoot: Have you seen it?

Plenty of Asian Americans watched Lost, and Jin and Sun may not be the primary reason all of us tuned in. But its importance as the first primetime American show to feature two central Asian characters who love one another goes beyond who your favorite castaway was, or which was your favorite season. (Or whether you thought the finale sucked.)

Jin and Sun emerged as two of the most endearing and beloved characters in modern American pop culture, and their relationship was one of the most complex and rewarding ever attempted on the small screen. Sure, they made mistakes, but they also cherished one another throughout the show’s six-year run. And their many hard-fought reconciliations brought tears to many of us who just wanted to see a couple make it—a couple that looked and felt a little like us.