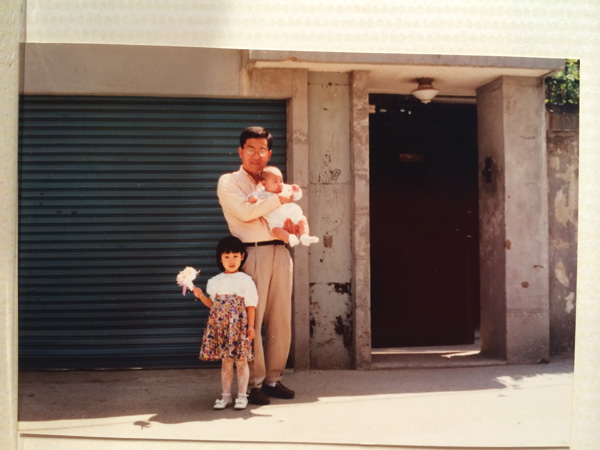

Above photo: Candy Koh, as a child, with her father and younger brother. (Courtesy of Candy Koh)

by STEVE HAN

In America, we’ve grown accustomed to seeing adult children of political candidates stump for their parents. Chelsea Clinton and Meghan McCain come to mind, as two daughters of former presidential hopefuls who had hoped to help capture the youth vote for their mother and father, respectively. So, when news broke this past summer that the New York-based daughter of a South Korean politician had taken to Facebook not to aid her father’s election overseas, but rather to derail him, it was a bit shocking.

It was also quite effective. Despite leading in all the polls going into the June 4 election to be the next Seoul education superintendent, Koh Seung-duk, a prominent attorney and popular TV personality, would end up losing to the Liberal Party candidate. Many observers blamed his daughter’s Facebook appeal, which urged the citizens of Seoul not to vote for the elder Koh. She argued that someone who neglected his own responsibilities as a father could not be entrusted with overseeing the education of their children.

The bold actions of Candy Koh, 27, drew a myriad of reactions from South Koreans—everything from empathetic support to harsh criticism for her utter lack of respect for her father. “He is still your father. You should never do that!” someone wrote her. Some even suggested that her father’s neglect of his family is “just the way it is in Korea.”

But Candy begs to differ, and she attempted to explain her controversial Facebook letter to the Korean media who swarmed her around the time of the election. However, soon, she realized these outlets had no interest in learning her motivations, but instead were focused on the circumstances of her parents’ 2002 divorce and petty family drama. It didn’t help that her own father accused her of teaming up with his conservative party opponent, Moon Yong-rin, to defame him, and suggested that this was a scheme cooked up by relatives of Koh’s former father-in-law, the well-known Park Tae-joon. (Park, Candy’s late grandfather whom she was close to, founded Korean steel giant POSCO, which led South Korea’s transition from a war-torn nation in the 1950s to one of the strongest economies in the world today.)

That’s when Candy, who attends law school in New York, grew frustrated and stopped all interviews. She told the Korean media to go away. However, when this magazine reached out to her, she said something felt right about addressing a Korean American audience with her story. “This is something Korean Americans can relate to,” she says. “I thought maybe this kind of critique [of a figure like my father] was possible from the outside—almost like my virtue of being in between Korean and American, understanding both. … I wanted to have that resonate in some way.”

Here’s more from the interview with Candy Koh.

When did you realize your family’s situation, in terms of your father’s isolation from the rest of the family?

I guess it was kind of dramatic. It was pretty clear that we lived in the same house until 1998 in Korea. So it was, at least ostensibly, an ordinary family, I suppose. But when we moved here to the U.S., he stayed behind in Korea. So it was just me, my mother and my brother. After we moved, there was little to no contact. That’s when I realized that this was over.

Why did your family move to America?

My mother wanted me and my brother to go to school here. She was concerned about the education system in Korea as a whole. And since we were U.S. citizens anyway (Candy was born in the U.S.), she wanted to educate us here.

When you looked at your family and other Korean American families, did you think that this is a story that a lot of people can relate to?

Even families who live together, I found out that there’s this big cultural divide between fathers and children who were raised here. There’s a different idea of what the role of a father is. Culturally, there’s this typical American fatherhood. You play, you learn how to ride a bike at a park, that showy kind of relationship. In the Korean culture, the father is the silent guy, but still the head of the family, the breadwinner who doesn’t actively show affection all the time. There’s also a lot of Koreans, they would come here to study with their mothers, and their fathers would stay behind in Korea and send over checks for tuition. I’ve seen a lot of that.

At what point did you decide to post that Facebook letter about your father. What made it important for you to make such a personal story so public?

After I left Korea, I heard about him occasionally. I heard about his public lectures on how to raise your kids and stuff. Then I heard he was running for superintendent of education. I was like, “How surprising. Another showpiece act for his list of achievements.” I really thought about it, and it made me angry. It was kind of ridiculous, you know? I really, really thought about this, because I wrote [the Facebook post] over and over and over again. I had a copy of this sitting for about 24 hours. Then I finally saw that he had a press conference (in response to his critics in South Korea who brought up his family issues). He cried and said, “Don’t touch my family.” He talked about my brother, but he doesn’t even talk to his son. It just seemed like he was using my brother as a tool to win a political favor. That was absurd and upsetting to me as a sister. That really made me want to post it. I’m protective about my brother, and when I saw that, I said, “I gotta post this.”

You mentioned that you don’t agree with the standard of success in Korea. Could you elaborate on that?

There’s a No. 1 student. Then there’s a No. 2 student. There are written exams all the time. There is a formula. There’s a way to get things done, and when you do that, you become No. 1. It’s all about adding as many lines to your resume as possible. There’ s no substantial kind of growth from experiences. Koreans I meet have outstanding CVs, but I can’t really have a conversation with them sometimes. I knew that Mr. Koh (Candy said she prefers to address her father as “Mr. Koh”) was a star because he has done every single thing right, according to the Korean education system. He was assured to win because of that. And I really disagree with that. It’s really suffocating. The situation was hypocritical from my point of view. So it was my way to tell people, “OK, think about this for a second. Do you really like going to hagwon in the middle of the night and waking up at 5 in the morning to go to hagwon again? And spending all day, every day, to pass your college exam? There’s something wrong here.” They shouldn’t be voting for these people who will just continue what they’re complaining about, you know? If we’re electing a public official, do you really care about how many awards he’s won? That’ s not what’ s important.

So what is your standard of success?

Finding something you really want to do, and knowing why you want to do it. And then, just devoting yourself to it. I think that’s what’s successful. People do things because they think they should. Sometimes it’s inevitable because they have to pay the bills, but I admire people who do what they want to do.

Would you say that there’s a social barrier for Koreans and even Korean Americans that keeps them from doing that?

Yeah, definitely. I have so many people in my immediate family or relatives who have done incredible things.

My biological father did everything right, according to the Korean education system, but he really thinks that the only way that a person can succeed is by studying really hard all the time. He put me down a lot. He would ask me questions, and if I couldn’t answer right away, he’d say, “You’re dumb.” Luckily, my mom was the complete opposite, where she really encouraged me to do whatever.

My grandfather from my mother’s side, he paved the Korean economy. I have doctors, lawyers, people who went to law school, but went to get their MBA at Harvard. How do I even compete with that? How do I even live halfway? I know a lot of Korean kids go through this. They feel like they have to be lawyers, doctors or at least make money. I felt that, too. But I wanted to do art, you know? I ended up majoring in art and literature, two of the most useless degrees according to Korean families. But that’s what I wanted to do. I really had to stop caring about what my family thinks because they’re not living my life. I’m living my life.

Then what made you want go to law school?

I never thought about going to law school until less than a year ago. I decided to write about art. I started working with galleries in Korea. I was doing translating, writing their press releases, just getting work that way. I see a lot of stuff happen, especially Korean American or Korean artists working in New York City. A lot of them come here because New York City is like the art hub of the world. They have this dream of achieving stardom. But what happens pretty often is that they don’t have much power in the art world.

I’ve seen artists get their ideas stolen, how their work gets stolen, and how more powerful artists’ names get on them. And they can’t do anything about it. They don’t have money to hire lawyers. I want to be more actively involved in how things operate because there’s so much crap going on … and it really shouldn’t be that way. I’m kind of naive, but I also just think that I can make a difference somehow. So I’ll hopefully continue to work with museums or galleries.

What message did you wish to send to people with your Facebook post?

I just hope they’re more open. I got a lot of messages from people, saying they received hope that there can be change. I don’t know how this past election will affect Korea, but I kind of wish that people can think that there are other ways of thinking about the standards of success. If you think something is wrong and you say something about it, there’s always hope [to change].

I’m sure you received a lot of negative messages from people as well.

Some responses were, “Oh, he’s still your father. You shouldn’t say that against your own parents.” But this wasn’t a matter of respect. There’s respect, and then there is right and wrong.

You had a chance to speak to your father after you posted that message on Facebook. What was that conversation like?

I didn’t converse with him, actually. He tried to send me messages [on KakaoTalk]. But I ignored it because it seemed like he was losing it towards the end, before the elections. Then after the elections he contacted me again, which I ignored, because it was really disappointing that he reacted that way to my Facebook post. He had his chance to redeem himself as a father. But he threw that away. I could no longer trust him. It’s really sad and disappointing when you’re shut down as a child. It’s really hurtful. And this time, it was really, really public. He considered me a lying puppet who is trying to seek revenge. What can I say?

He also gave that public TV apology before the elections—it was very dramatic. (Koh gave a speech on the busy streets of Seoul, during which he raised his hand and screamed a high-pitched “I’m sorry, my daughter!” The image of his apology quickly became a meme, as his photo was Photoshopped to depict him as a rockstar and comic book superheroes.)

[Laughs.] That’s when I received the confirmation that people started seeing through the ridiculousness, the bad acting. The memes are an indication that it’s not taken really seriously. When I first saw the original clip, he wasn’t talking to me. He could’ve said sorry to me directly. It was clearly a show, and the show turned really bad, because of bad acting. It was shocking to me. I was just shocked.

Do you have plans to reconnect with him ever?

I’ll respond at some point. A good, fair amount of time needs to pass. But I won’t give up [the possibility of reconciling our relationship].

This article was published in the August/September 2014 issue of KoreAm, under the title, “Papa, Don’t Preach.” Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the August/Sept. issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only. Expect delivery in 5-7 business days).