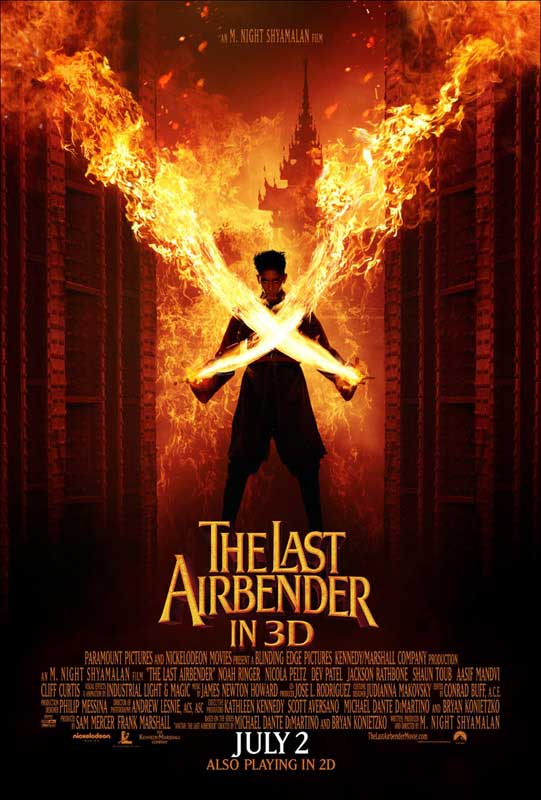

I’m gonna be honest: I could give a damn about The Last Airbender. I didn’t watch the beloved cartoon series Avatar: The Last Airbender and after seeing the trailer for M. Night Shyamalan’s film adaptation — sans “Avatar” because of that punk Jim Cameron — it looked like an overlong, melodramatic cheese fest that would not be getting my $9.00 later this summer.

My disinterest in the film has perhaps contributed to my vague following of the Asian American-led protest of the movie’s casting which has the hero Aang played by a little white boy and dark-skinned Asians as the villains. It’s like I get what the anger is about yet have no connection to it on a personal level. And with the post-production schedule lasting for what seems like decades, the Internet-driven rallying has now been reduced to a buzzing in my ear.

You have to admit, this is one doozy of a film to try to dissect as “racist” or “not racist.” You’ve got an Asian American director adapting an animated cartoon series where everyone is a bit ethnically ambiguous and is from imaginary worlds. There’s no red flag “Pearl Harbor reference and subsequent group beating of an Asian man” scene to really get everyone riled up.

Yes, I thought Paramount’s initial casting notices privileged white actors (who are privileged enough in Hollywood as it is) and yes, I think it’s fantastic that the folks at Racebending and other groups have fought so passionately for a boycott of the film as well as for more advocacy for actors of color.

But after reading M. Night Shyamalan’s response to the alleged racism, I kind of agree with him. Is he smug and defensive and spewing a well-rehearsed diversity/colorblindness ethos? Of course. Is his film gonna suck something fierce anyway? Most likely.

But he also says this:

“And here’s the irony of it, this has nothing to do with the studio system. I had complete say in casting. So if you need to point the racist finger, point it at me, and if it doesn’t stick, then be quiet.”

The casting was his artistic decision as an Asian American filmmaker. It’s not one many of us agree with, but then again, I haven’t agreed with his last three artistic decisions, namely The Happening, Lady in the Water, and The Village. Haven’t we fought — and don’t we continue to fight — for Asian American artists to exercise some kind of autonomy in an industry that was built on our very exclusion?

Asian Americans have long waged a war — and rightfully so — on our representation in entertainment media and the tension often exists internally, between those who are “down” and those who “sell out.” We should always keep a critical within and outside of Asian America, but there is no uniform way to “get in line.” Some see The Last Airbender‘s casting as a step back for Asian American actors while some see Shyamalan’s helming of a $150 million studio film featuring different races as a step forward. The truth is: it can be both. But trying to chip away at its existence doesn’t tip it to one side or the other.

I’m not quite sure what the end game is for The Last Airbender boycott. We hope that an Asian American filmmaker tanks at the box office, making him less viable in an industry that has little to no love to people of color as is? Granted, he’s not exactly small potatoes, schlepping it on the indie festival circuit, but if he screws up, I’m fairly sure his career will go down in flames way quicker than someone like Stephen Spielberg or Ron Howard. I guess the boycott is a good tactic in terms of showing studios that pissed-off Asians can potentially be a detriment to publicity and box office sales; our collective power as a consumer group is what will open the door to more Asian American representation in entertainment. But once you’ve torn The Last Airbender down, then what next? Hopefully, building something up is on the agenda.